Medieval manuscripts are normally displayed for a maximum of three months, to keep their glowing colours as fresh as when they were first painted. But the 150 manuscripts featured in the Fitzwilliam Museum’s exhibition of its rich collection—many of which came from the 1816 founding bequest of Viscount Fitzwilliam—will be on display in Cambridge for a full five months. The show Colour: the Art and Science of Illuminated Manuscripts (until 30 December) is part of the UK institution’s 200th anniversary programme.

The works are exposed to no more than 50 lux lighting, a level that prevents fading and requires a short adjustment to the darkness as you enter the exhibition. “There isn’t a dedicated display area for manuscripts in the museum that does justice to its collection, so these rarely see the light of day,” says Stella Panayotova, the Fitzwilliam’s keeper of manuscripts and printed books. “Since they haven’t been on show for the past ten years and probably won’t be for the next ten, five months will be fine.”

Busting the myths The extended dates are by no means the most groundbreaking aspect of this exhibition, which has science—contemporaneous and contemporary—at its core. Four years of ongoing analysis, headed by the research scientist Paola Ricciardi, has revealed information about pigments, techniques and workshop methods, as well as giving more clues about the painters themselves. “If you want to know the story of painting and colour in the Middle Ages and early Renaissance, you have to look at manuscripts. Nothing else is preserved in such large numbers and condition,” Panayotova says.

For example, one of the myths that the exhibition busts is that manuscript painters did not use egg yolk tempera to bind their pigments, preferring egg white or tree resin instead. An analysis of a cutting of Christ the Redeemer (Florence, around 1409; additions from around 1450) shows that every pigment in the figure of Christ has been bound with egg yolk; in the ornamentation behind, likely painted by an assistant, there is none. Panayotova believes that this demonstrates how the master artist, likely trained as a panel painter, treated his assistants more as helpers than apprentices, unlike the more romanticised view of a workshop.

Intense pigment analysis has also revealed the first-known example of smalt (made by crushing blue glass) in the cutting Dormition of the Virgin (Venice, around 1420), which links the painter to the Murano glassmakers in Venice. Research into this artist will continue outside the exhibition, in partnership with the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

The Fitzwilliam show reinforces how much science informed artists at the time. A fascinating example is a page showing St John’s Eagle (Northumbria, early eighth century), from the collection of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and one of a handful of significant loans to the exhibition. Here, the painter shows an absolute understanding of his corrosive materials—including lead and copper. Carefully isolated buffer zones, made with untouched canvas and ink, protect the colours from flaking or blackening.

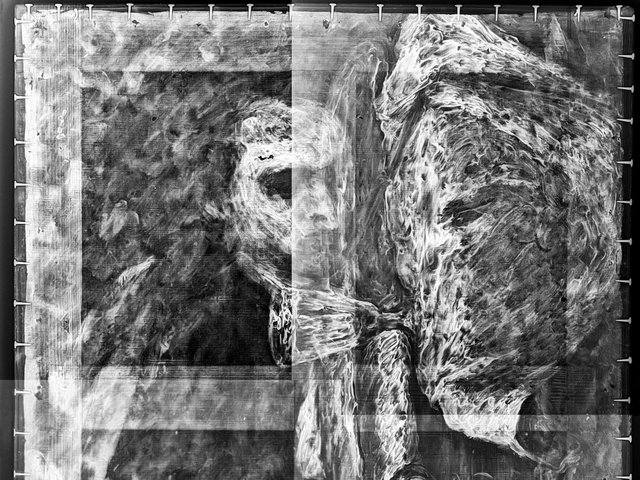

Physics as well as chemistry The more recent research had to cater to some distinct properties of the manuscripts—generally very small and painted on parchment, a live material made from animal skin, which does not lie flat. Analysis was done through spectroscopy (using light’s reflection and refraction), with the highly sensitive equipment kept at least one centimetre above the parchment. “It’s physics as well as chemistry,” Panayotova says.

She and Ricciardi had hoped that Cambridge University’s many science laboratories would provide the necessary equipment but it soon became clear that this was not the case. New equipment—to the tune of more than £200,000—was funded by a private benefactor and now puts the museum in an enviable position. “We can use this equipment on works across the collections. This exhibition is just phase one,” Panayotova says.

A free, in-depth and interactive digital resource—Illuminated: Manuscripts in the Making—forms part of the exhibition and is also available online (www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/illuminated), supported by Arts Council England. So far, detailed analyses of 20 manuscripts, including the Macclesfield Psalter (Norwich, around 1330-1340), are included, with the aim of adding more over time.

Exhibition Highlights

Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden

(Paris, 1414) The Master of the Mazarine Hours

• This stunning manuscript, an encyclopaedia made for Amadeus VIII, the Count of Savoy, welcomes visitors to the exhibition but has more behind it than its glowing colours. Its 18th-century binding was a wreck, leaving the manuscript in pieces, so the Fitzwilliam’s conservator, Edward Cheese, made a new structure, based on 15th-century techniques. The project took 214 hours to complete. To watch his work, visit www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/gallery/utc

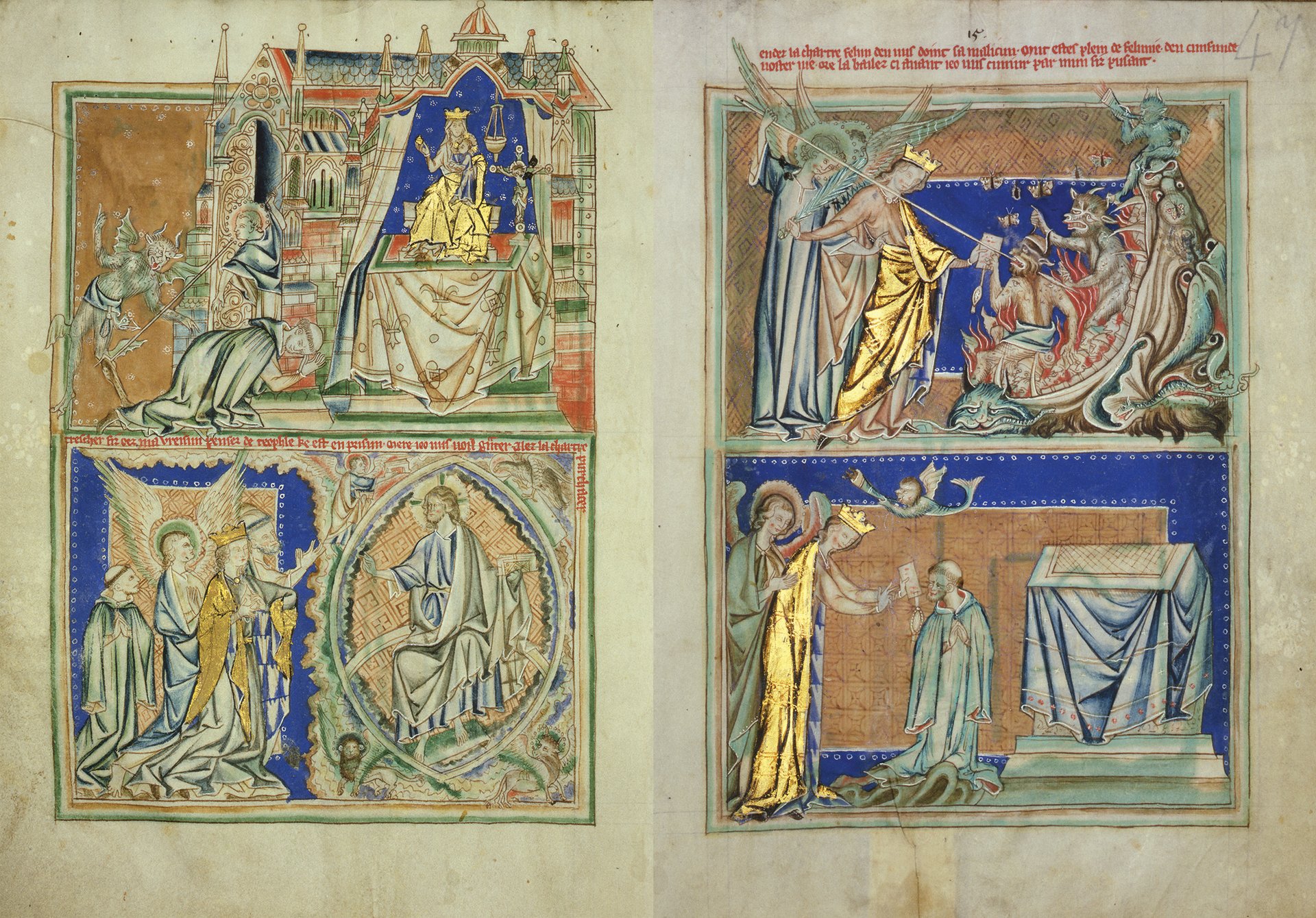

The Story of Theophilus

(probably London, around 1260-67)

• The Lambeth Apocalypse, with its 78 images of St John the Evangelist’s visions, is one of the exhibition’s choice loans. The work brings illuminators’ technical skills to the fore and includes one of the earliest known examples of a red, translucent lacquer painted on the Virgin Mary’s gold robe to create shadows, more associated with 14th-century Italian painters. London’s Lambeth Palace has agreed that the Fitzwilliam can analyse the manuscript after this exhibition. (Other lenders have agreed the same.)

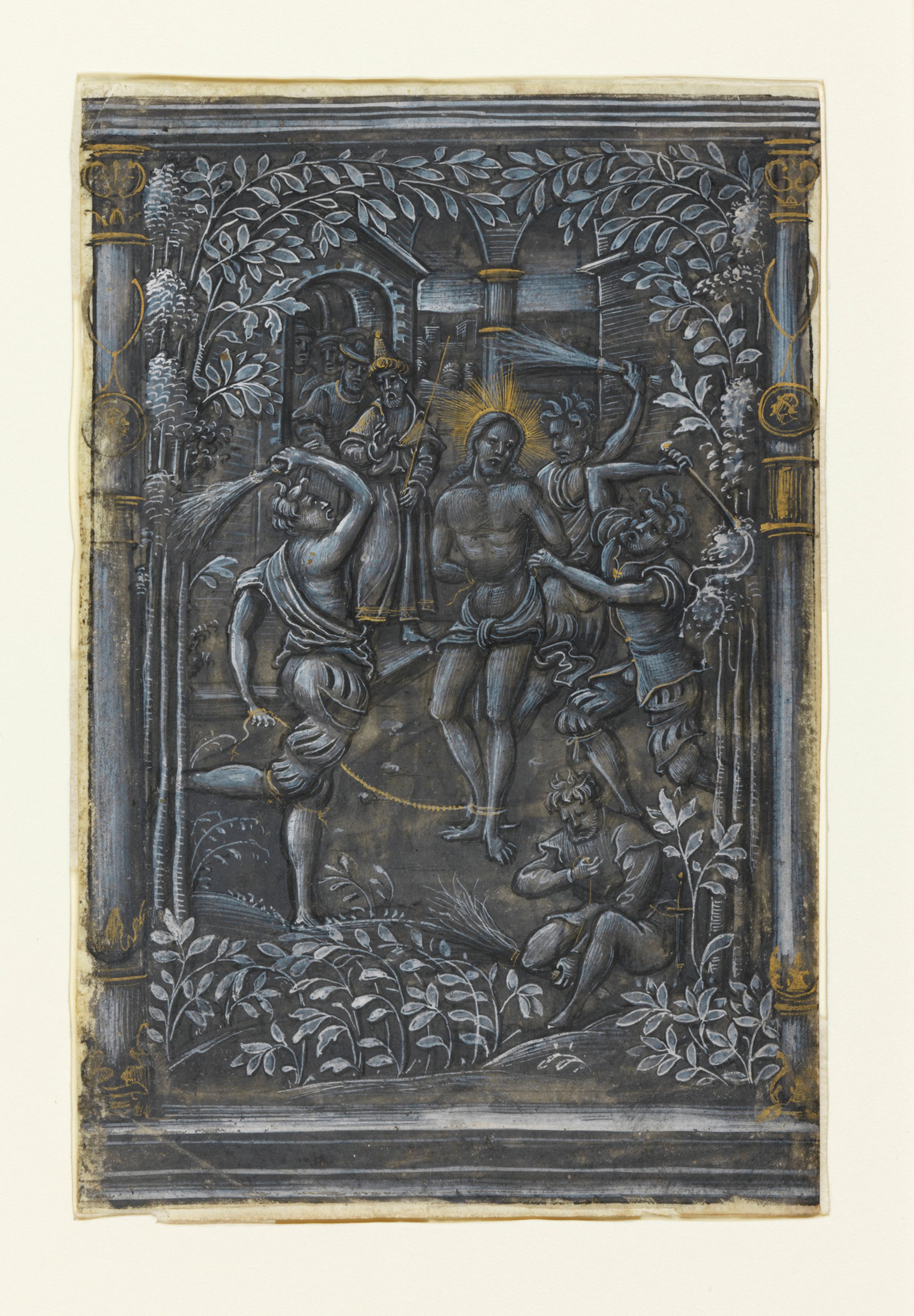

Flagellation

(Rouen, around 1530) The Master of Girard Acarie

Although the exhibition is focused on colour, there is one area dedicated to the minimal materials used in grisaille—painting in shades of grey. Pigment analysis shows that this work, one of a set of five miniatures, uses a rare “antimony black”, while the other four use the more widely available, carbon-based black. This, together with a finer style and technique, makes it likely that it was completed by the master and the others by his assistants.