Many of today’s younger Chinese artists have turned their sights inward to consider how the nation’s social and economic issues impact their lives. But Chinese contemporary art is still probably best known abroad for its overt polemicists, not least Ai Weiwei or Wang Guangyi, who through the 1990s battled obscurity and repression. Now hotly collected, their works reflect an earlier time of upheaval and rapid change.

Examples of Cynical Realism and Political Pop by this pioneer generation can be seen in the works on show in the M+ Sigg Collection at ArtisTree in Hong Kong (until 5 April).

Among today’s crop of artists is Dongguan-based Li Jinghu, who collected migrant workers’ mobile phones to create Waterfall (201603) (2016), a digital cascade of water at Magician Space’s booth (1C27) and on hold for a museum. Also at the fair, Sun Xun’s video Time Vivarium (2015) at Sean Kelly (1D09) references China’s endangered environment. He is also represented by ShanghArt (1C17) and Edouard Malingue (3C09).

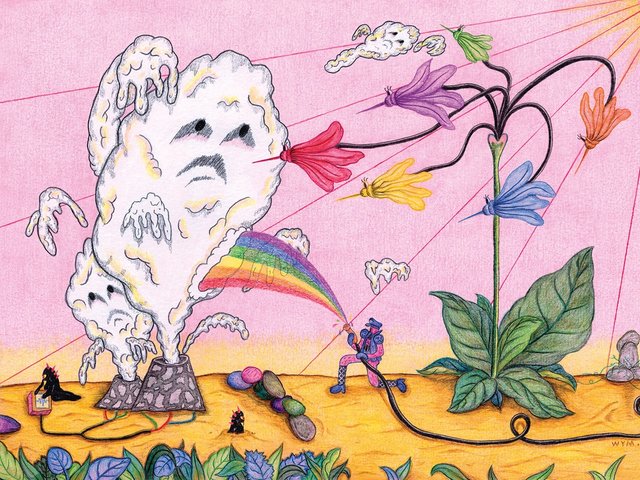

Meanwhile, 2015 Venice Biennale artist Lu Yang has a fascination with the pollution of the human body; she has previously created works about cancer and Parkinson’s disease. Art Basel’s Film programme includes her work Delusional Mandala (2015).

Cosmin Costinas, the director of Hong Kong’s Para Site, which often explores Asian society through group shows, says the work of today’s artists “reflects a certain milieu, a vision of urban dystopia, that the ‘Chinese dream’ is not there anymore.” There is, he adds, a reaction to previous artists “who are very literal”. Because of intensifying censorship, younger artists avoid the direct approach, he says.

Para Site’s latest exhibition on migration and domestic labour, Afterwork (until 29 May), includes work by the duo Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, who have been commissioned by the Guggenheim, supported by the Hong Kong-based Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation, to create works for a show in New York in November. Also part of the Guggenheim’s Chinese Art Initiative are their similarly socially engaged contemporaries, Kan Xuan and Sun Xun.

Mass migration and workers’ rights inform the practice of some younger artists, particularly those with rural roots or who live near southern China’s vast factories; Li Liao worked in a Foxconn plant for 45 days, the time it took to earn enough to buy one of the iPads made there. In Shanghai, the performance troupe Grass Stage delves into Chinese manufacturing with their work World Factory (2014), as does Li Xiaofei, who will debut an issues-based work at the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai (Tell Me a Story: Locality and Narrative, 28 May-14 August).

“Rather than move to Shanghai or Beijing,” says the Magician Space curatorial director Billy Tang, Li Jinghu decided “to buck the trend and stay resolutely based in his hometown” in the Pearl River Delta region. He is one of a number of noteworthy Chinese artists associated with the industrial region, such as Chu Yun and Liu Chuang.

The ecological byproducts of production often emerge as a theme in younger artists’ work—sometimes explicitly, such as with performance artists like Nut Brother, who vacuumed Beijing smog into a brick. Kong Ning made a wedding dress from face masks. Costinas cites Cao Fei as a progenitor of today’s young artists who explore their digital identities despite China’s online censorship. “She has a talent for capturing the spirit of contemporary China as well as of global society,” he says. “I can’t say that of the previous generation.”