Fleeing the Nazi invasion, Walter Benjamin (1892-1940), the author of The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, died mysteriously in the small Catalan town of Portbou 75 years ago. To commemorate his death, we are publishing an extract from Walter Benjamin’s Archive, which Verso is releasing in paperback to coincide with this anniversary. The book is based on Benjamin’s personal collections of objects, which he posted to friends and colleagues when his life was in danger in war-torn Europe. We have focused on Benjamin’s collection of postcards.

Buying, writing, sending, receiving, reading, and collecting picture postcards featured in Walter Benjamin’s life from childhood into his adult years. He enjoyed all the uses of a medium that was barely as old as he. The first polychrome picture postcard, manufactured according to a photographic template, appeared three years after his birth. Just two months after their introduction more than two million pictorial postcards had been bought.

But picture postcards were not only bought and sent en masse. They were also quick to become items that inflamed the passions of collectors, and Benjamin too fell victim. Over the course of the years the medium of the picture postcard itself became a focus of his philosophical interests. In 1924-25 he planned a publication that was intended to include an essay on the “Aesthetics of the Picture Postcard”. It would appear that this publishing plan collapsed, but his interest in a written confrontation with the phenomenon of the picture postcard remained.

Walter Benjamin on his postcards

There are people who think they find the key to their destinies in heredity, others in horoscopes, others again in education. For my part, I believe that I would gain numerous insights into my later life from my collection of picture postcards, if I were to leaf through it again today. The main contributor to this collection was my maternal grandmother, a decidedly enterprising lady, from whom I believe I have inherited two things: my delight in giving presents and my love of travel. If it is unclear what the Christmas holidays—which cannot be thought of without the Berlin of my childhood—meant for the first of these passions, it is certain that none of my boys’ adventure books kindled my love of travel as did the postcards with which she supplied me in abundance from her far-flung travels. And because the longing we feel for a place determines it as much as does its outward image, I shall say something about these postcards.

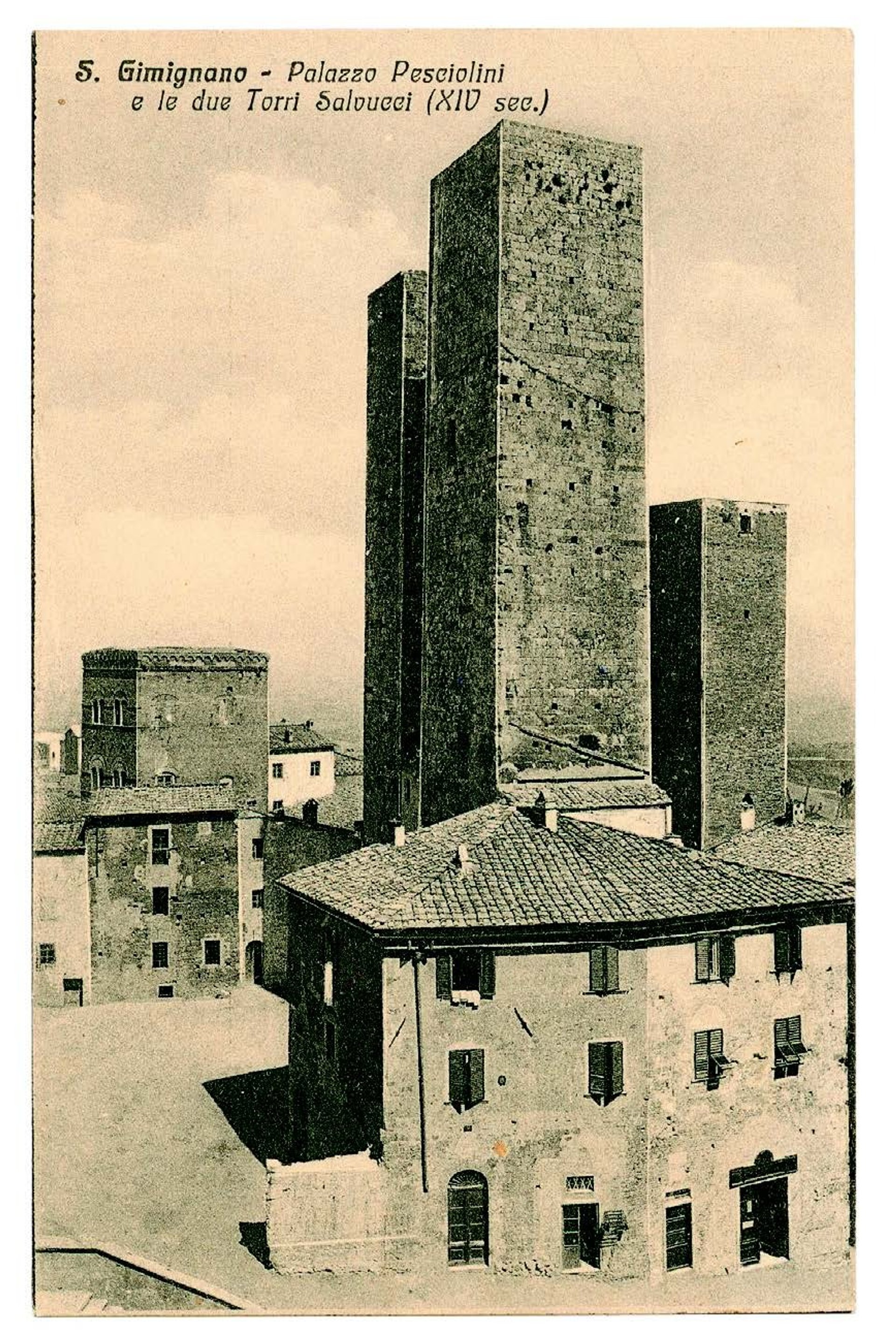

On San Gimignano

If one arrives from far away the town is suddenly as noiseless as if one had stepped through a door into landscape. It does not give the impression that one could ever manage to come any closer. But should one succeed, then one falls into its lap and cannot find oneself again for all the humming of grills and children’s cries.

Over the course of many centuries its walls consolidated themselves ever more thickly; barely a house is without the traces of large rounded arches over its narrow gate. The openings, in which now dirty linen cloths blow gently as a protection against insects, were once bronze doors. The remains of the old stone ornamentation have been left poking godforsaken from the masonry, which lends it a heraldic air. If one enters through the Porta San Giovanni, one feels as if one is in a courtyard, rather than on the street. Even the squares are courtyards, and one feels secure on all of them. What one often encounters in the towns of the south is nowhere more tangible than here; that, in order to get what one needs for life, one must first make the effort to visualize it, because the line of these arches and battlements, the shadows and the flight of the doves and crows make one forget one’s needs. It is difficult to escape from this exaggerated present, in the morning to have evening before one and in the night the day.

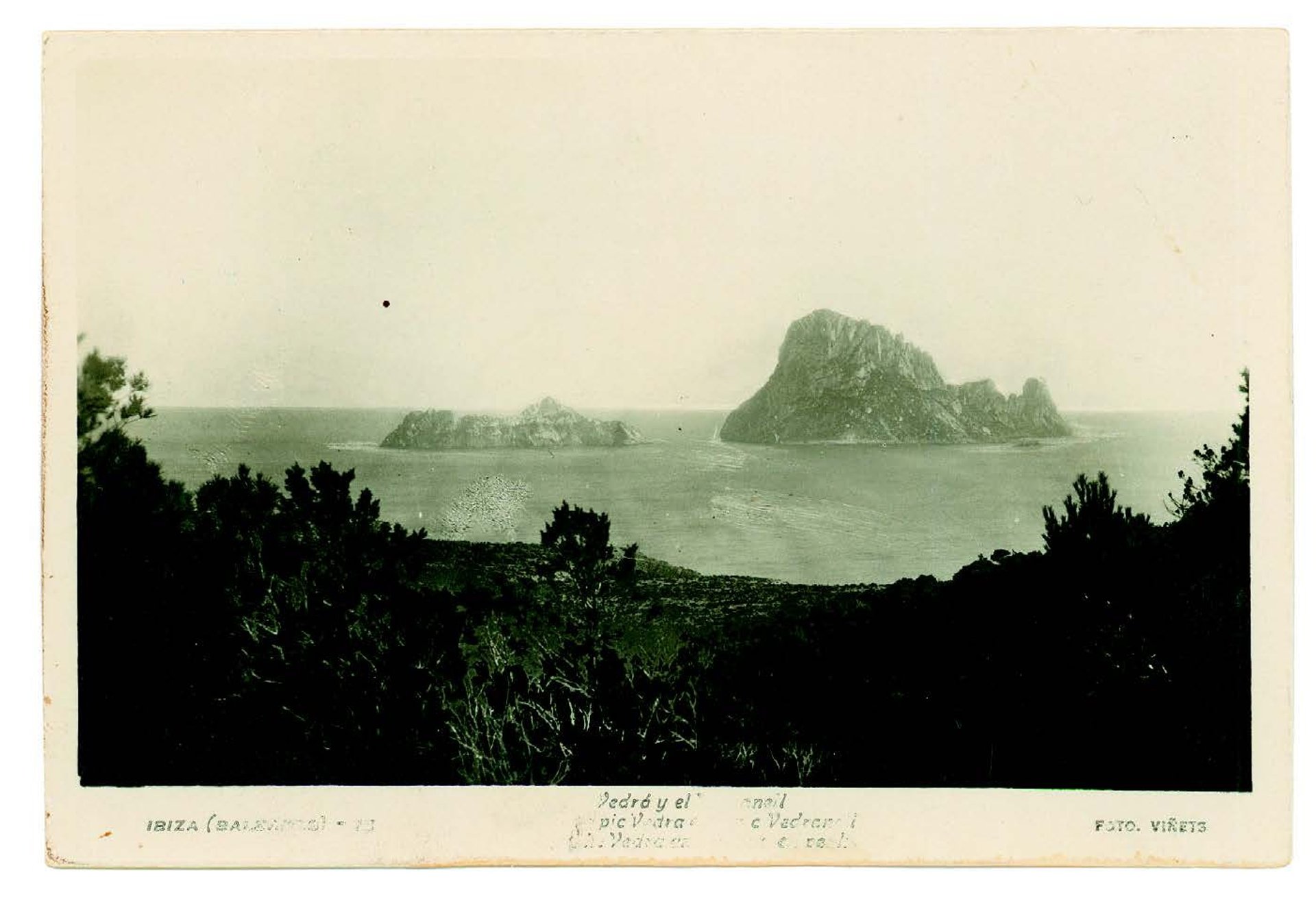

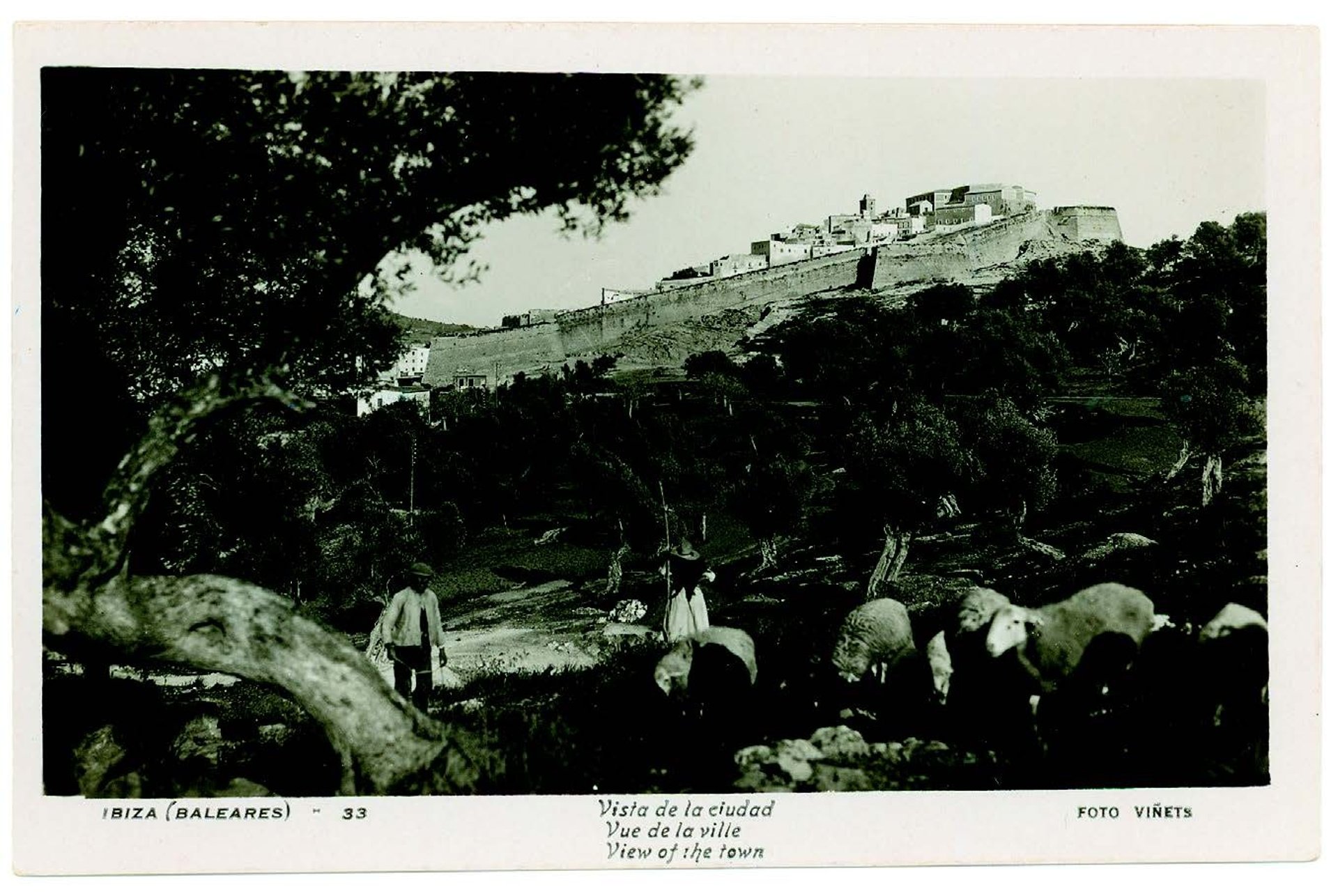

On Ibiza

I had been living for a few months in a rocky eyrie on Spanish soil. I often resolved to set out into the environs one day, as it was bordered by a ring of severe ridges and dark pinewoods. In between lay hidden villages; most were named after saints, who might well have been able to inhabit this paradisiacal region. But it was summer; the heat allowed me to postpone my resolve from day to day and I even wished to save myself from the cherished promenade to Windmill Hill, which I could see from my window. And so I stuck to the usual meanders through the narrow, shady alleyways, in whose network one was never able to find the same hub more than once. During my wanders one afternoon I came across a general store, where postcards could be bought. In any case some were displayed in the window and amongst their number was a photo of a town wall. Many such walls have been preserved in numerous places in this corner of the land, but I had never seen one quite like this. The photograph had captured all of its magic: the wall swung through the landscape like a voice, like a hymn singing across the centuries of its duration. I made a promise to myself that I would not buy the card before I had seen with my own eyes the wall that was depicted on it.

The next afternoon I stumbled suddenly upon my general store. The picture postcard was still hanging in the window. But above the door I read on a sign, which I had missed before, in red letters “Sebastiano Vinez.” The painter had included a sugarloaf and bread.

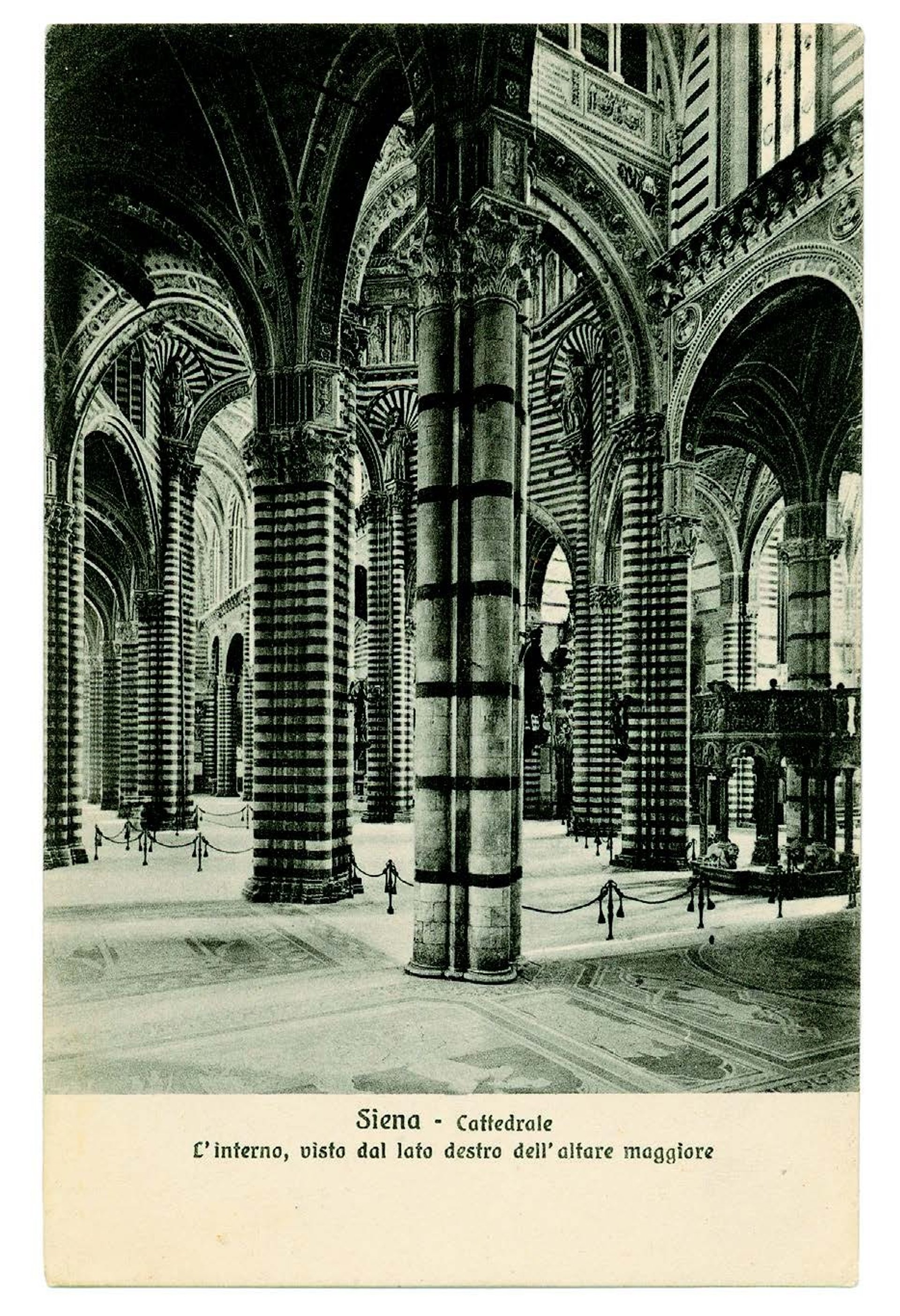

On Siena

Ritual teaches us: the church did not build itself up by overcoming the love between men and women but rather homosexual love. That the priests do not sleep with the choir boys is the miracle of the mass (cathedral at Siena July 28, 1929)