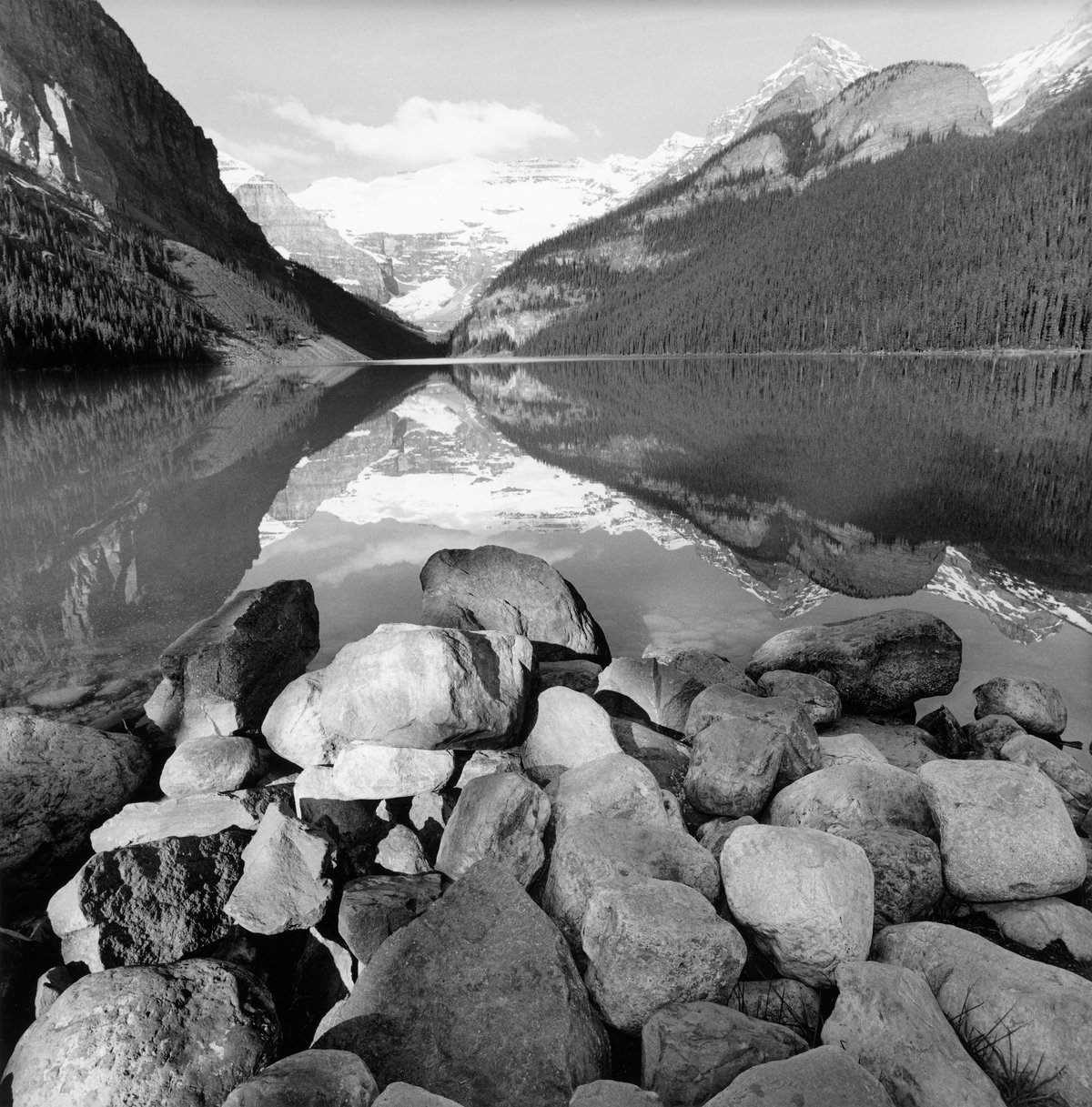

Lee Friedlander was born in 1934, when photography was less than a hundred years old. He is now over 80, and if he manages to keep working for another 14 years, he will have lived for the entire second half of the history of photography up to that point. He used a 35 mm camera for many years, producing tremendously innovative and visually rich pictures of rectangular shape, but then, in the 1970s, when he fell in love with the American West and pounced upon it as a subject, he switched over to a wide-angle view impressed upon a square format. He traveled to the land of the big sky and picked a picture shape that encompassed it. The old horizontal rectangle got the landscape photographer off the hook by chopping off most of the sky, but Lee decided this great blank chunk was one of the central challenges of photographing the landscape. Edward Weston, the most elegant and skilled of them all, could push the horizon up to the top of the frame, laying out the swirls and turns of the land before him, and Ansel Adams could drag out his red filter to fill the sky with bursting clouds as another way to solve the problem. Lee decided to confront things head on. Unlike those other two great photographers, he never sought the beautiful and balanced ideal landscape that had satisfied their minds.

What is it that Friedlander does that makes all these pictures work so well, that lets them deliver a brand-new landscape that has none of the conventional patterns of organization? We never feel that this photographer has stood for hours until the light is exactly right, nor do we suspect Lee of carrying around a hatchet, as the young Ansel did, to remove an offending tree. If we look carefully at these pictures, it becomes obvious that almost all of them have been taken with a flash, regardless of how bright the sunlight was. It is also plain that Lee has bodily walked right into the landscape he is photographing, stuffing the lens into the bushes, letting its extremely wide angle of view gather every twig and branch, setting them up as an array through which bits of the conventional “landscape” can be glimpsed. Every picture has some form of the dance between foreground and background, and every picture pulls these two pictorial aspects together to make a single unified scene. The strings of wood and reed weave a screen described by light, through which we can see bits of the land that retain a familiar look in spite of being relegated to the distant background.

I started traveling with Lee in the early 1970s. We both were interested in America, and this interest often led us to the West. I was a first-rate printer and second-rate photographer, and these trips let me blow off steam after hand-developing thousands of halftone negatives in a stinking, dripping darkroom. When Lee and I were at home, we both lived in rooms with almost no light—exposing and developing pictures day in and day out. I wised up and stopped doing this in the early nineties, when digital cameras came along, but Lee still does it—day in and day out. The odds are that when he finally goes to his reward he will do so by collapsing into either a bed or a tray of hypo.

Our travels were soon enriched by the addition of two Johns—John Szarkowski and John Childs. Szarkowski was toward the end of his time as curator of photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Childs was a commercial photographer from Houston, the son of Szarkowski’s sister. We became an extremely odd foursome that went off on annual trips to photograph. There were ten years of age between each of us, so at one time John C. was forty, I was fifty, Lee was sixty, and John S. was seventy. The two younger guys felt very privileged to be in the presence of the two old wise guys, but what a strange pair they were. One (John) talked incessantly and the other (Lee) was almost totally silent. One made a few pictures each day—maybe a total of six, one or two of which he would inadvertently re-expose the next day. The other made literally hundreds. When we stopped the car and got out, John would walk for ten minutes, studying the surroundings, and then—slowly—set up his 4 x 5 camera to expose a single frame. During this time Lee would be walking constantly, only stopping for a moment here and there to expose a picture. By the time we ended back in the car, the respective picture count between the two old guys was 1:30.

No one had a better mind than John Szarkowski, and his writing gave us all the intellectual framework for the photography of Walker Evans and Eugène Atget. Before John became a curator he was a superb photographer, and his books on the Midwest banks of Louis Sullivan and the life of Minnesota are absolute treasures. Once he had retired after nearly thirty years at MoMA and found himself o_ in the car with the three of us, his pictures changed. They became less frequent and less technically assured but were still rich with the benefits of that mind behind the lens and tripod.

Lee, in contrast, kept his mind at close quarters. We would all talk, chuckle, and laugh, but no analysis of the world came out of Lee—he was just too busy seeing and photographing to have time for talk. His walks and work were silent and immensely productive. Once back home he would develop eight rolls of 2¼-inch film simultaneously by inspection and then proof hundreds of pictures from each trip. I could hardly lift his carry-on bag of film, packed with heavy silver he had exposed to the world in front of his lens.

I describe all this because the real issue of Friedlander’s work is that it is first and foremost work itself. If you ask him what he was thinking when a particular picture was made, he will react with gen¬uine puzzlement; he wasn’t thinking anything about meaning, and he certainly never had an idea of what was going on in the picture as some piece of art. Meaning had to wait until later, when the picture was developed and printed and perhaps had passed the test of being worth keeping. Only then would an idea creep into the work, but usually just a simple, basic one, perhaps about how many other pictures he had made of the same subject, or how often he had visited and worked at the same place. Lots of monuments led to his understanding that he was interested in monuments, and so a book resulted. Lots of trees and mountains with the square camera led to this book, one that only had a clear subject after the work was largely completed.

There is a war in art today between the work and the word. The word is in ascendancy, sustained by flows of written criticism and hours of heated discussion in classrooms and seminars, while the work is almost beside the point, something created because history requires it and the market feeds upon it. We have reached the extreme point, particularly with regard to photography, where many “artists” even have someone else do their work. The physical work itself has become so secondary that the old belief that the artist possesses a magical manual gift has faded away, and the efforts of skilled technicians have become adequate to fill the intellectual needs of contemporary art. Perhaps this change has its root in those dreadful printmaking ateliers where wonderfully talented craftsmen executed the hollow work of the renowned artist, who merely made his mark on the printing plate, leaving the difficult part to the skills of others to execute.

I give this tirade because it is totally relevant to Friedlander’s practice. He never goes out the door without a camera, and he photo¬graphs constantly. When at home he is always in the darkroom, and his faithful Maria, like my Barbara, spends her days alone wishing she could see more of her husband while being grateful that he is down in the dungeon working and not bothering her all the time. The days are long, repetitive cycles of exposing and printing; when on the road, rolls of silver film are wrecked each day, and when at home, a box of 11 x 14 paper disappears into the washer each morning. It is all about the work and not the word in their house.

If you ask any biologist what is more miraculous—the mind or the hand—you will undoubtedly be told the mind takes the prize. This remarkable wet thing we carry around in our heads is the most complicated known object that we are aware of; it is the force behind all the great stuff we have made. The hand does its work in response to the directives of mind and the senses, and in the realm of art, the result is some physical object that can be accessed by all of us and that—when cared for—can outlive its maker. Then, even though a mind once stood behind it, the physical thing is all that remains. The mind dies, the talking stops, and even the best-written pieces about art go thank¬fully unread outside of academic circles. In the end the word loses and the work wins. We don’t know what Rembrandt or Mozart thought or said, and we really don’t care. The pictures and the music are what transfix us, and immortality rests in them rather than in the mind that produced them.

From Western Landscapes by Lee Friedlander; with an essay by Richard Benson and an afterword by Jock Reynolds, to be published by Yale University Art Gallery and distributed by Yale University Press in September 2016. Reproduced by permission.