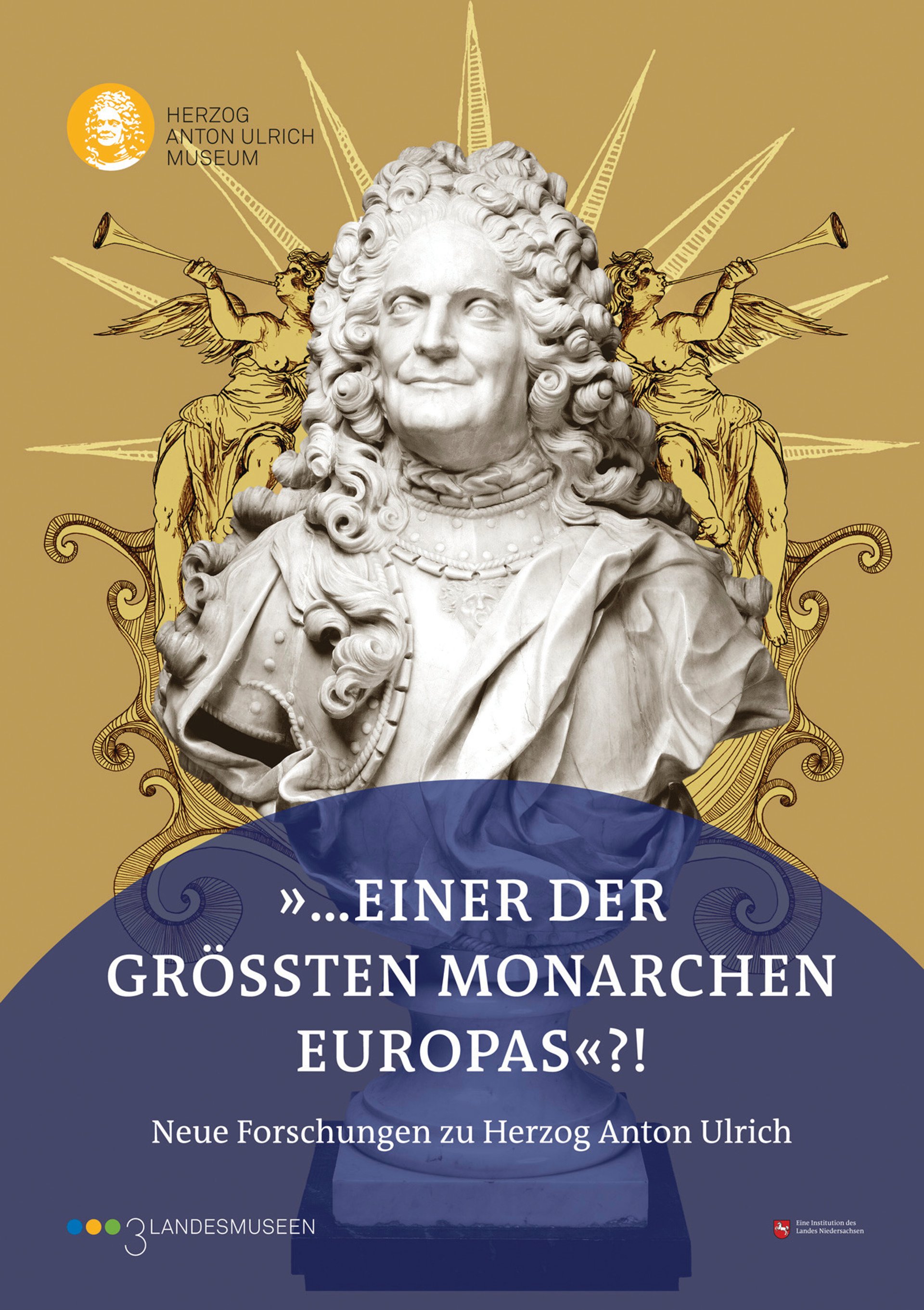

“If achievements and aspirations were to count, then the duke would be one of the greatest monarchs of Europe.” Few today would recognise the man referred to by the Duchess of Orléans (1652-1722), Louis XIV’s sister-in-law, also known as Madame or Liselotte of the Palatinate. She meant Duke Anton Ulrich of Braunschweig-Lüneburg-Wolfenbüttel (1633-1714), with whom she corresponded over several decades. She greatly admired his wide-ranging cultural achievements, including his additions to the main residence at Wolfenbüttel, such as a spectacular rotunda to house the book collection started by the dukes in the 16th century and the construction of a magnificent new country palace at Salzdahlum. This featured the first purpose-built, free-standing art gallery in the Holy Roman Empire.

Conceived to mark the tercentenary of Anton Ulrich’s death, “…Einer der grössten Monarchen Europas”?! Neue Forschungen zu Herzog Anton Ulrich, a richly illustrated volume edited by Jochen Luckhardt, complements Das Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum und seine Sammlungen, which Luckhardt edited in 2004. The present book contains valuable new essays on the role of art in the politics of the Holy Roman Empire, and on Anton Ulrich’s acquisitions. This provides a fascinating insight into the duke’s collecting practices and their relation to the politics of the later 17th and early 18th centuries.

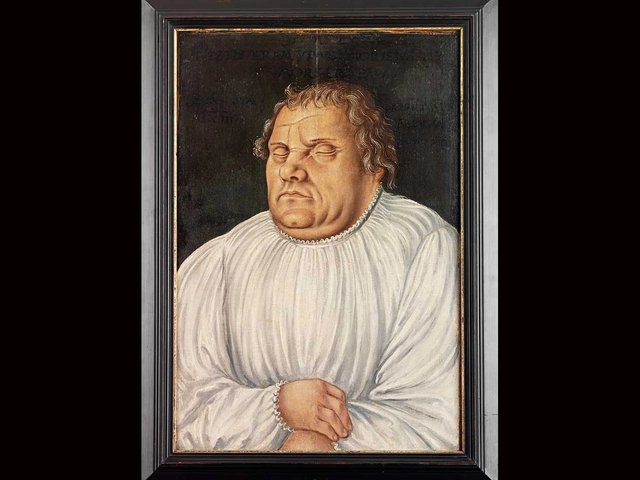

Liselotte’s reference to “aspirations” certainly captures the central theme of Anton Ulrich’s career. The second son of Duke August the Younger (1579-1666), he was made co-regent by his brother Rudolf August (1627-1704) in 1685. The elder brother preferred building churches to governing, and remained without a male heir. Anton Ulrich was fired by the ambition to assert the position of his line against the equally fierce ambitions of his Calenberg-Göttingen-Grubenhagen cousin Ernst August, who, however, won a decisive victory when Emperor Leopold I created him Elector of Hanover in 1692. This drove Anton Ulrich into a French alliance, which nearly cost him his duchy in 1702. A rapprochement with Vienna led to the marriage of his granddaughter to the young Charles III of Spain, later the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI; another granddaughter married the Tsarevich Alexei, son of Peter the Great. In 1710, he followed his first granddaughter in converting to Catholicism—like her, almost certainly for political reasons.

Anton Ulrich’s collections undoubtedly reflected his personal taste, but they also played an important role in his political life. As the superb chapter by Friedrich Polleross on networks of art and representation in the Holy Roman Empire from Rudolf II to Leopold I makes clear, the emperors not only gave and received works of art as gifts, but also reinforced their political networks using portrait series of electors and other princes by favoured court painters, printmakers or sculptors. Leopold I and his son Joseph I even sent pictures and plans of their building works to princes throughout the empire as part of a campaign to lim it the influence of French styles.

Despite an early Grand Tour to France (1655-56) and his later flirtation with a French alliance, only 3% of the 800 paintings in Anton Ulrich’s collection in 1714 were French. His focus was on Italian and Dutch works, with around 25% of his collection devoted to each country. Visits to the Venice Carnival from 1680 enabled him, like other nobles from all over Europe, to browse the art market while also enjoying the city’s theatre, opera and music. He took home works by Titian, Veronese, Francesco Montemezzano, Bernardo Strozzi and Jacopo, Francesco and Leandro Bassano, among others.

Equally important were his purchases in the Netherlands. Here, Anton Ulrich seems to have been guided by the list of Dutch painters that Joachim von Sandrart included in his Teutsche Academie der Edlen Bau-, Bild-und Mahlerey-Künste (1675-79). His favourites were historical paintings; he acquired few landscape or genre pictures and almost no still-lifes. These choices were mirrored in the German and Flemish paintings that made up 23% and 18% of the collection respectively.

How to impress your guests

Anton Ulrich displayed his pictures at Salzdahlum. This gave him great pleasure but also served to entertain and impress distinguished guests. Peter the Great visited in 1713 and left his host bemused by insisting on kissing all the religious pictures. When he came to a bronze statue of Nero, the tsar stared at it intently before giving the Roman emperor a few hefty slaps in the face.

Luckhardt and his contributors shed new light on the world of collecting in the Holy Roman Empire. Their book must be consulted by anyone interested in the history of German taste. Readers will also no doubt make a note of the need to visit the Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum in Brunswick. The Salzdahlum palace, built as a timber-frame structure, was demolished in 1813, and many of its treasures are now displayed in the museum.

“…Einer der grössten Monarchen Europas”?! Neue Forschungen zu Herzog Anton Ulrich

Jochen Luckhardt, ed

Michael Imhof Verlag, 208pp,

€29.95 (hb); in German only

Joachim Whaley is professor of German history and thought at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of Gonville & Caius College