Typical of 19th-century European perspectives on ancient Egypt is this observation from Lord Cromer, head of the Antiquities Service in the 1880s: "The Egyptians are as yet not civilised enough to care about the preservation of their ancient monuments…no moral guilt of any kind is attached to the offense, which is considered as absolutely venial…We say to the Egyptians: we civilised governments care about their monuments. If you pretend to be a civilised nation you ought to care about them too."

The same might be said by an antiquities dealer today, without the altruistic motive of taking an interest in monuments. Egyptians' perceived indifference to ancient Egypt helped fuel the antiquities trade in the early 1800s. So did greed and the weakness of local governments. Modern European archaeology and travel to Egypt boomed soon after Napoleon's campaign there, as did the pillaging of sites. As early as 1835, Muhammad Ali condemned the looting of ancient objects and ordered a ban on the export of antiquities and the creation of a place where they could be seen and studied in Egypt. Yet Egyptian participation in the growing field of Egyptology would be slow until at least World War I. The locals had to crack a European monopoly.

Besides the now familiar tales of conquest, pillage, study, preservation and blithe tourism throughout the 19th century, Dr Reid's narrative follows the competitive campaigns by Britain and France to control excavation sites and museums.

Each group of foreign travellers accused the other of the worst abuses. Yet purists will also be reminded that trade, transport and tourism fuelled the study of antiquities, even 200 years ago.

It was a mixed blessing. Demand from tourists helped open sites to study and travel— and to freelance souvenir-hunting. For Egyptians, guiding tourists was sometimes the first step toward scholarly training.

It comes as no surprise that a condescending British official like Lord Cromer might not appreciate the plight of Egyptians trying to study and work in a practice reserved for Europeans. The shifting balance there and its components—education, sovereignty, and the assimilation of the pharaonic past into a national identity—are elements in the story that Dr Reid tries to tell. It was Europeans who created the field of study, but usually Armenians and Syrians, rather than French or British, took the lead in training the local population..

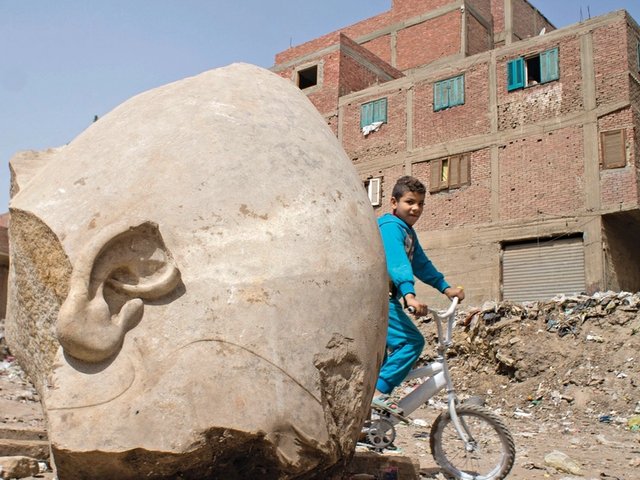

The bias was not all in one direction. Islamic hardliners then (and now) scorned the veneration of the idolatrous pharaonic past and feared promoting a heritage that they associated with Christians of the Coptic Church. And why would not ordinary Egyptians question preserving the pre-Islamic past?

Rich in detail, Dr Reid's study reminds us how distant cultures were one from another, almost inevitably so under colonialism. British experts could read ancient Egyptian, yet few were competent in Arabic. It was not until the end of the 19th century that more than a few Egyptians could read ancient inscriptions on the façade of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, or that an Arabic language transaction of the Iliad was completed.

"Whose Pharaohs?" ends with independent Egyptians as the stewards of their own sites, with millions of most European tourists visiting every year (despite episodes of terrorism), and the study of monuments more collegial than competitive. Pyramids and the Nile are icons that all Egyptians share in their popular culture, currency and postage stamps. Or do they? When hardline Islamists shot Anwar Sadat, they declared, "We have killed Pharaoh." Will monuments be the next targets?

As always, studying and preserving the past is political. "Whose Pharaohs?" examines more than a century of that political journey. Almost a century later, with more of that heritage damaged, the journey is not over.

"Whose Pharaoh's? Archaeology, Museums, and Egyptian National Identity from Napoleon to World War I" by Donald Malcolm Reid.