Don McCullin’s career began almost by chance in 1958, when a portrait he took of a local north London gang was accepted for publication by the Observer. Six decades later, one of the greatest post-war photojournalists—who has covered conflicts from Northern Ireland to Vietnam—will have a major retrospective at Tate Britain.

Although an art institution may not seem the most obvious place for a McCullin retrospective, “it’s very clear throughout his entire career he was always doing things that you wouldn’t consider photojournalism”, says the show’s co-curator Simon Baker. “He was always making portraits, he was always doing landscapes. If you take the most historic notion of genres in art, he was always engaged in that,” Baker says.

The exhibition of more than 250 silver gelatin prints, hand-printed by McCullin in his darkroom at home, will include some of his most famous war photographs alongside what he refers to as “a sprinkling of new surprises”—never before printed photographs selected from his archive of 60,000 negatives. McCullin sees the exhibition as an opportunity to “show what I’m really made of” and the inclusion of social documentary and landscape photography—taken in winter when “you actually see the character of the trees”—demonstrates the breadth and diversity of his life’s work.

Now in his 84th year, McCullin says he “can see the horizon” where his journey in photography will probably end. But he continues to take photographs. Some of the most recent pictures in the exhibition are of the ancient city of Palmyra—before and after it was damaged by Islamic State—from a body of work he plans to add to soon, visa permitting, by travelling to photograph the ruins of Persepolis in Iran.

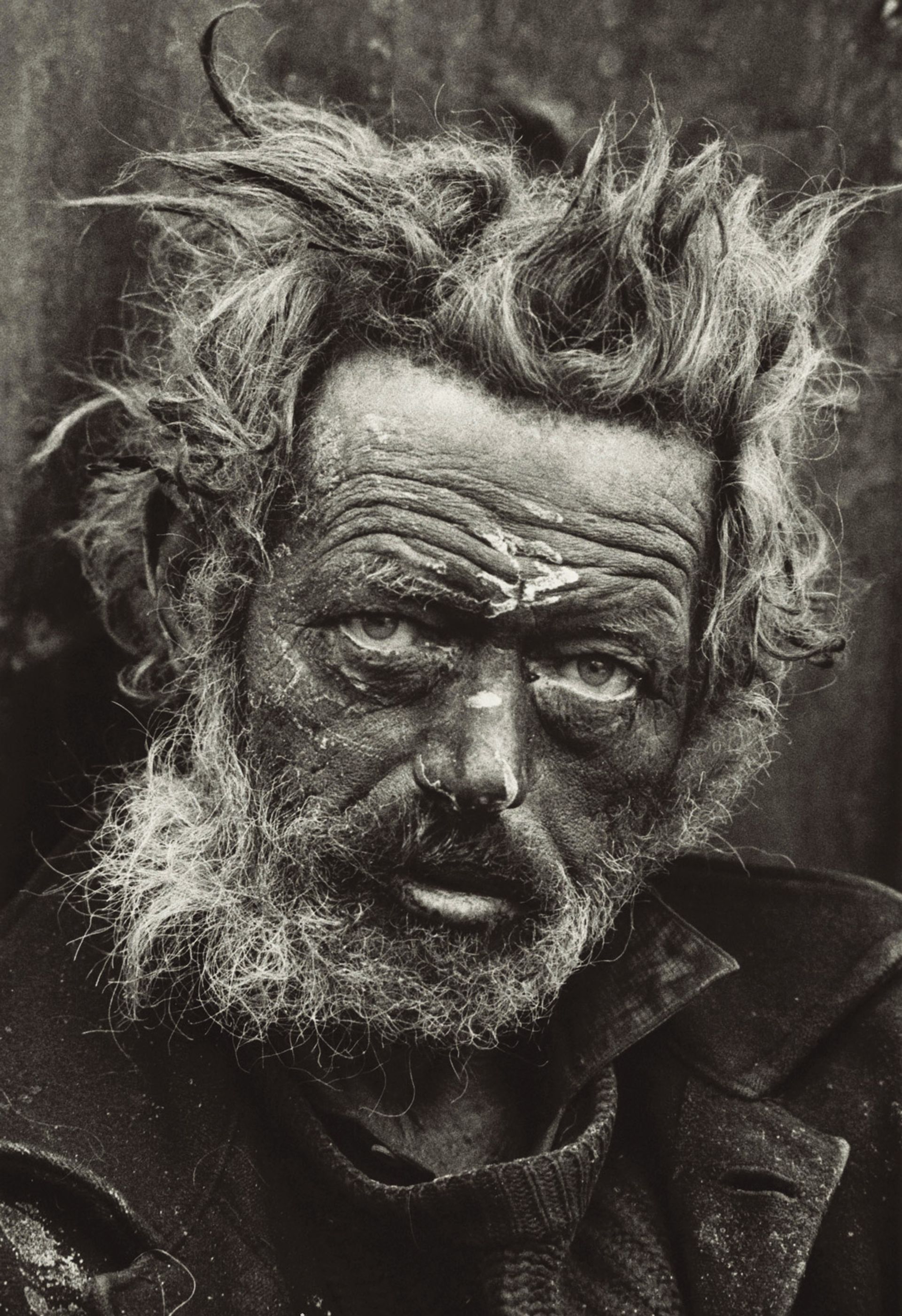

Homeless Irishman, Spitalfields, London (1969) by Don McCullin © Don McCullin

The Art Newspaper: How do you feel about being invited to exhibit at Tate Britain?

Don McCullin: I’m in a very funny place: I’m in an art gallery and yet I’m a photographer saying I don’t want to be an artist. The reason I’ve agreed to be involved, apart from the honour of it all, is that if I leave my photographs in yellow boxes in my house, no one will ever see the work I’ve done that condemns war, famine, starvation and tragedies. It’s a great opportunity to release the propaganda of all the evil things I’ve seen in the world, which are not humanly right. So that’s my justification in putting my work, as a photographer, in an art gallery. But I’m not an artist.

Were there particular stories you wanted to tell in the exhibition?

There were four really important things I did in my life, photojournalistically. I did a story about homeless people in England in 1971, which is a very topical subject now. Another story was a great battle in Vietnam in 1968 during the Tet Offensive. And there were two others: the Biafran War and the war in Bangladesh, where it was very much like the people now in Burma, the Rohingyas, who are fleeing into Bangladesh.

Grenade Thrower, Hue, Vietnam (1968) by Don McCullin © Don McCullin

Some of your photographs are very difficult images to look at.

I’ve walked this [moral] tightrope all my life and been very aware of it. I’ve tried not to discredit myself in these areas of tragedy; I’ve always been very careful how I operate. But, after all, nobody invites you to their murder or their death.

On the other hand, most of the things we see in our newspapers today have all been self-censored. The media has got very much away from urgent news stories. I’m sick to death of Jamie Oliver, the Beckhams, Gordon Ramsay, footballers and good-looking film-stars in newspapers. It’s pure narcissism. And that is not giving the unfortunates in this world a voice. We need a balance now and we’re not getting it.

In this context, what do you think an exhibition can do?

I’m trying to reverse the situation but it’s only a fleeting glance. We have a newspaper every day; we don’t have an exhibition like mine every day. I don’t want it to be a painful experience to go and see these pictures. I want people to come away saying, “God, is this going on in the world? Should this be right? Shouldn’t we stop that?”

Your more recent work includes an ongoing project photographing the remains of the Roman empire across North Africa and the Middle East. What interests you about these ruins?

I love their dignity, which in fact was built at the expense of other people’s dignity. These monuments were built with terrible cruelty and cost of life and yet we go and stand in front of them thinking how beautiful they are. I do like photographing them though. When you’re photographing them, they do not move, so you’ve got all the time in the world to do it properly.

Woods near My House, Somerset (around 1991) by Don McCullin © Don McCullin

Your war photographs have often been described as iconic...

That can be a mistake, using the word iconic, because in a way it turns my photography into a kind of compositioned work that borders on the art world. But I like to keep photography really pure. I’m a bit prickly about this art stuff.

What do you mean by “pure” photography?

Well, it’s based on chemistry, of course, because you need film, emulsion, printing paper and silver. But I’m using light the way painters use light. I tend to actually like looking at paintings; I think they’ve helped my photography. I’m not very clever at the technical side of photography. I believe my photography comes from my emotion. It doesn’t come from my cameras; it comes from the way I see and feel things.

I went down to buy some newspapers this morning and I saw these amazing trees. I came back, got one of my cameras and I drove all the way back down into the village and photographed those trees. It was only for a few minutes, but my God, I was so happy. I won’t let go of photography, at my age even. I won’t let go.

• Don McCullin, Tate Britain, London, 5 February-6 May