A drawing of the interior of a Gothic church by Adolph Menzel in the exhibition Gurlitt: Status Report, Nazi Art Theft and its Consequences at the Bundestkunsthalle in Bonn is one of very few works in the show whose provenance is known.

It was hidden for decades in the home of the reclusive hoarder Cornelius Gurlitt, who at one time had a secret trove of more than 1,500 works of art, many of them since seized by authorities. Earlier this year, the drawing was returned to the heirs of Elsa Helen Cohen, who sold it under duress in 1938 to Cornelius’s father, Hildebrand Gurlitt, an art dealer to the Nazis, to fund her escape to the US.

“It is very important to us to tell the human stories behind these works—the stories of the mostly Jewish owners who were expropriated,” says Rein Wolfs, the Bundeskunsthalle’s director and a co-organiser of the show. He hopes the exhibition will encourage more claimants to come forward.

The exhibition opens today (3 November), the day after a parallel show called Gurlitt: Status Report, Degenerate Art Confiscated and Sold opened at the Kunstmuseum in Bern, which inherited the entirety of Cornelius Gurlitt’s controversial collection. While the Bonn show focuses on Nazi art-looting from private individuals, most of whom were Jewish, the Bern exhibition explores the venomous campaign of Joseph Goebbels against art the Nazis deemed “degenerate” and seized from German museums.

It is an explosive subject, it is important and everything must be as transparent as possible

Aside from being one of just four dealers permitted by the Nazis to sell degenerate art abroad for hard currency, Hildebrand Gurlitt acquired works that had been stolen from Jews, or sold by Jews desperate to leave the country. He ran his own dealership in Hamburg and shopped in occupied Paris during the war for Adolf Hitler’s planned Führermuseum in Linz, Austria, a project that never came to fruition.

When Cornelius Gurlitt died in 2014, the unsuspecting sole beneficiary of his will was Bern’s Kunstmuseum, which hesitated before accepting his legacy because of the responsibility it carried. It eventually reached an accord with the German government, which continued investigating the provenance of Gurlitt’s collection. Only works free of the taint of Nazi looting would enter Swiss territory.

But Gurlitt family members contested Cornelius’s testament, arguing that he was not mentally capable of making a will. The dispute was only resolved in December last year, when a Munich court ruled in Bern’s favour. Until then, Bern could not inherit the trove, and Monika Grütters, the German culture minister, was forced to delay the Bonn exhibition, which was initially planned for 2016.

Kunstmuseum Bern. Bequest of Cornelius Gurlitt 2014

The Bundeskunsthalle is showing around 250 works, most of which are either known to have been looted or whose provenance remains unclear. Works by Max Beckmann, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Aristide Maillol, Albrecht Dürer, Edgar Degas and Auguste Rodin are included. The majority are works on paper, with about five sculptures and around 60 paintings, Wolfs says. Two photo albums of works of art destined for the Führermuseum are also on display.

“We didn’t want to wait another five years until there is clarity on more works,” Wolfs says. “The longer we wait, the harder it will be to examine this dark chapter of history. It is an explosive subject, it is important, and everything must be as transparent as possible.”

The Bonn and Bern shows will be combined for an exhibition at Martin Gropius Bau in Berlin in autumn 2018.

• Gurlitt: Status Report, Nazi Art Theft and its Consequences, Bundestkunsthalle, Bonn, 3 November-11 March 2018

• Gurlitt: Status Report, Degenerate Art Confiscated and Sold, Kunstmuseum, Bern, 2 November-4 March 2018

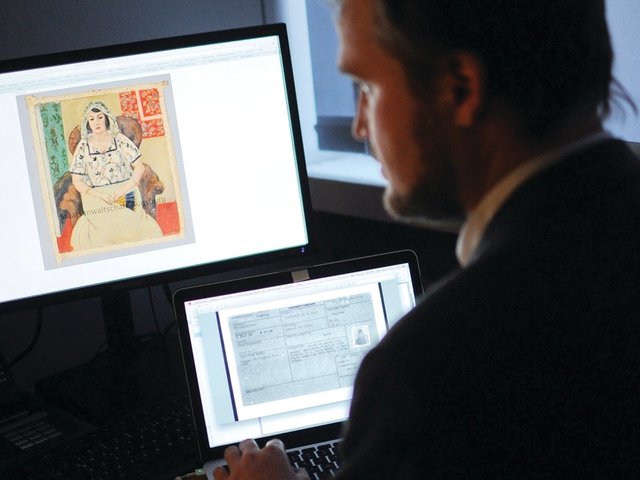

David Ertl. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Bern

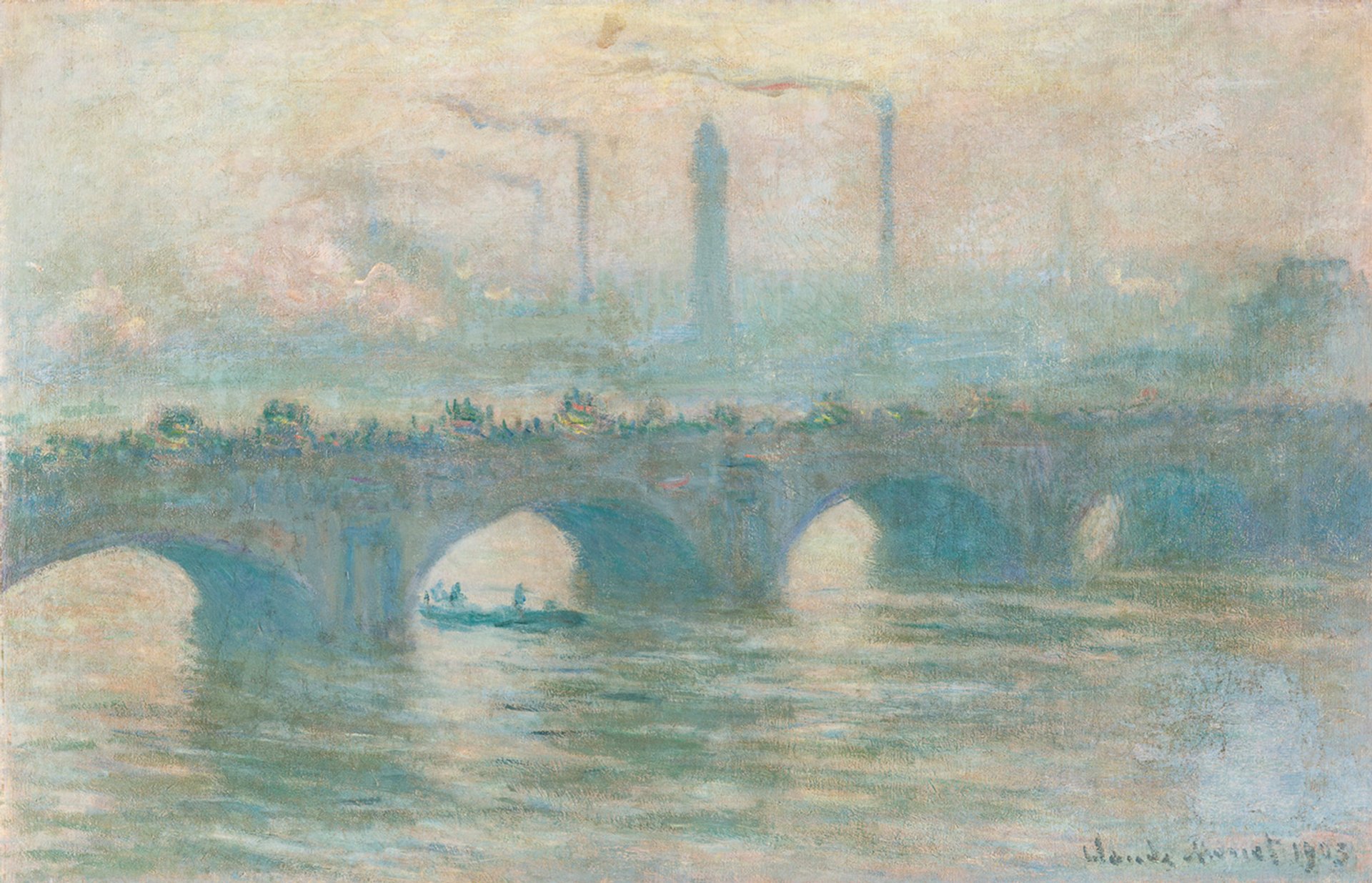

- THE MONET HIDDEN BEHIND A BOOKCASE

Claude Monet’s painting of Waterloo Bridge (1903) was found wrapped in newspapers behind a makeshift bookcase in Cornelius Gurlitt’s Salzburg home. The oil-on-canvas picture is one of many Monet produced of the same scene, in this case on a grey and misty London day. The back of the painting presents an equally murky scenario. Attached is a note from Marie Gurlitt to her son, Hildebrand, dated 1938: “I am happy to confirm that this painting photographed overleaf was purchased by Father for me many years ago and I gave it to you on your wedding in 1923.” The note raises more questions than it answers. Why did she wait until 1938 to write it—15 years after the supposed wedding gift was made? Was the story even true? Quite possibly not, Wolfs says. Hildebrand Gurlitt lied extensively about the provenance of his art collection on several occasions and may have enlisted his mother to help in a cover-up for any number of reasons. Wolfs says the painting is one of “very many works in the exhibition whose provenance is not clear”.