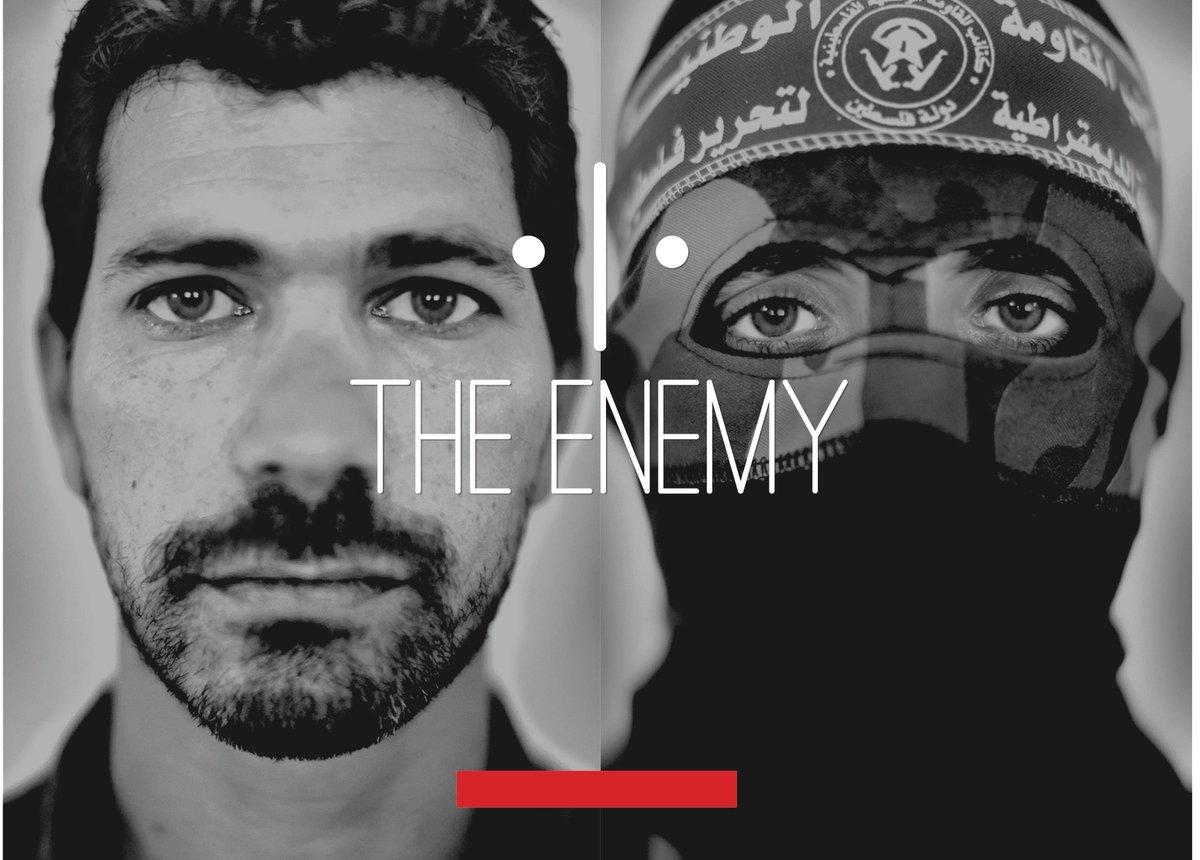

“We understand the world through stories,” says the Belgian-Tunisian photojournalist Karim Ben Khelifa, who has created an interactive VR experience, The Enemy, where visitors can “meet” fighters on both sides of longstanding conflicts and hear their stories in their own words. Inspired by his 15 years of reporting from conflict zones, Ben Khelifa worked with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) digital media and artificial intelligence professor Fox Harrell during a fellowship at the MIT Open Documentary Lab in Boston in 2013-15 to develop the project, which made its North American début at the MIT Museum in Boston last week (until 31 December).

The Enemy takes participants—or “passengers”, as Ben Khelifa likes to call them—on a 50-minute experience during which they encounter six fighters, two from each side of conflicts in Israel-Palestine, the Democratic Republic of Congo and El Salvador, as they wander through a 3,000 sq. ft space. Khelifa whittled down a selection of fighters based not only on their storytelling ease, but also sought a relative uniformity in size, rejecting outliers in height so that size wouldn’t skew visitors’ reactions to each person.

In a 360-degree audio and video experience, visitors come face-to-face with the fighters, who answer two types of questions: about their enemies (who they are, why they want to kill them) and then about themselves—“what is peace to you, what is violence to you, do you have nightmares, what are the most beautiful moments of your life”, Ben Khelifa says. They talk about their children, the future, their suffering.

Each visitor’s experience is customised due to The Enemy’s use of cognitive science and AI-based interaction technology. In the final section, based on the amount of time a visitor has spent “interacting” with each fighter, they walk towards a mirror and see themselves as one of the fighters, who mirrors the visitor’s own motions. The fighter you’ve become “assimilated to” tells you something about peace and hope, Ben Khelifa explains.

“We hope to humanise the other in the face of war. Not a specific war, but rather to bring to light the aspirations for peace and a positive future that exists across boundaries,” Harrell says. The show has already “brought” opposing sides together in its presentation in June at the Tel Aviv International Student Film Festival. “In real life, an Israeli would walk away from a Palestinian fighter, but here they get closer,” Ben Khelifa says.

So far, at the Israel presentation and the début presentation at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris in May, there have been two main types of immediate reactions upon exiting the experience, Ben Khelifa says. Around 70% of people “speak straight after”, often talking with people such as staff collecting the headsets ( “I hope I didn’t mess up your headset, I was crying”), while others “walk around and they still need to figure it out”.

After MIT, The Enemy, which was developed by the Montreal-based digital creation studio Dpt. and the National Film Board of Canada will travel to cities in Canada including Montreal, and Ben Khelifa also aims to present it in the conflict zones depicted in the work.

So does Ben Khelifa think that VR is a means to create a more empathetic world? “This medium is extremely powerful [and] offers a lot of possibilities for understanding the other,” he says, though “if you can bring people together, you can also divide people really easily”. It depends on the people who are using the tool—it’s just a tool, he adds. “You can build a house with a hammer, but you can also kill a chicken.”