The estate and foundation of George Rickey, whose kinetic steel sculptures combine technological innovation with balletic choreography of geometric forms, are now being represented exclusively worldwide by Kasmin gallery. Next fall, in tandem with displaying three of Rickey's works on its rooftop sculpture garden prominently visible from the High Line, the Chelsea gallery will help sponsor an exhibition uptown on Park Avenue of nine monumental pieces spanning the artist's mature work from the early 1960s to just before his death in 2002 at age 95.

“The outdoor sculptures have a wonderful receptiveness to light and local climate conditions and particularly along the High Line and Park Avenue—these thoroughfares in the city that are also about movement and constant changing perspectives—it will be a really nice dialogue,” says Nick Olney, Kasmin’s director. It will be the largest show of Rickey's work in New York since his 1979 retrospective at the Guggenheim, which included works poised on the roof and at street level.

“It’s a major opportunity for Rickey being seen anew in New York,” says Philip Rickey, the artist's son, who had worked with Marlborough for the last decade but felt Kasmin's outdoor space and long-standing commitment to public sculpture offered the best context for his father’s large-scale work. Such pieces by Rickey range in price from $750,000 to $1.5m.

As a young child, the artist first learned about kinetic movement through his grandfather, a clockmaker. “The pendulum is instrumental to every moving work my dad did,” Rickey says. His father studied painting in Paris and worked in the Social Realist mode before joining the Army Air Corps during the Second World War, when his childhood love of tinkering was put to use working on gunnery sites for B-29 bombers. He then started making little mobiles, inspired by Alexander Calder, and for the last five decades of his life dedicated himself to movement as an art form.

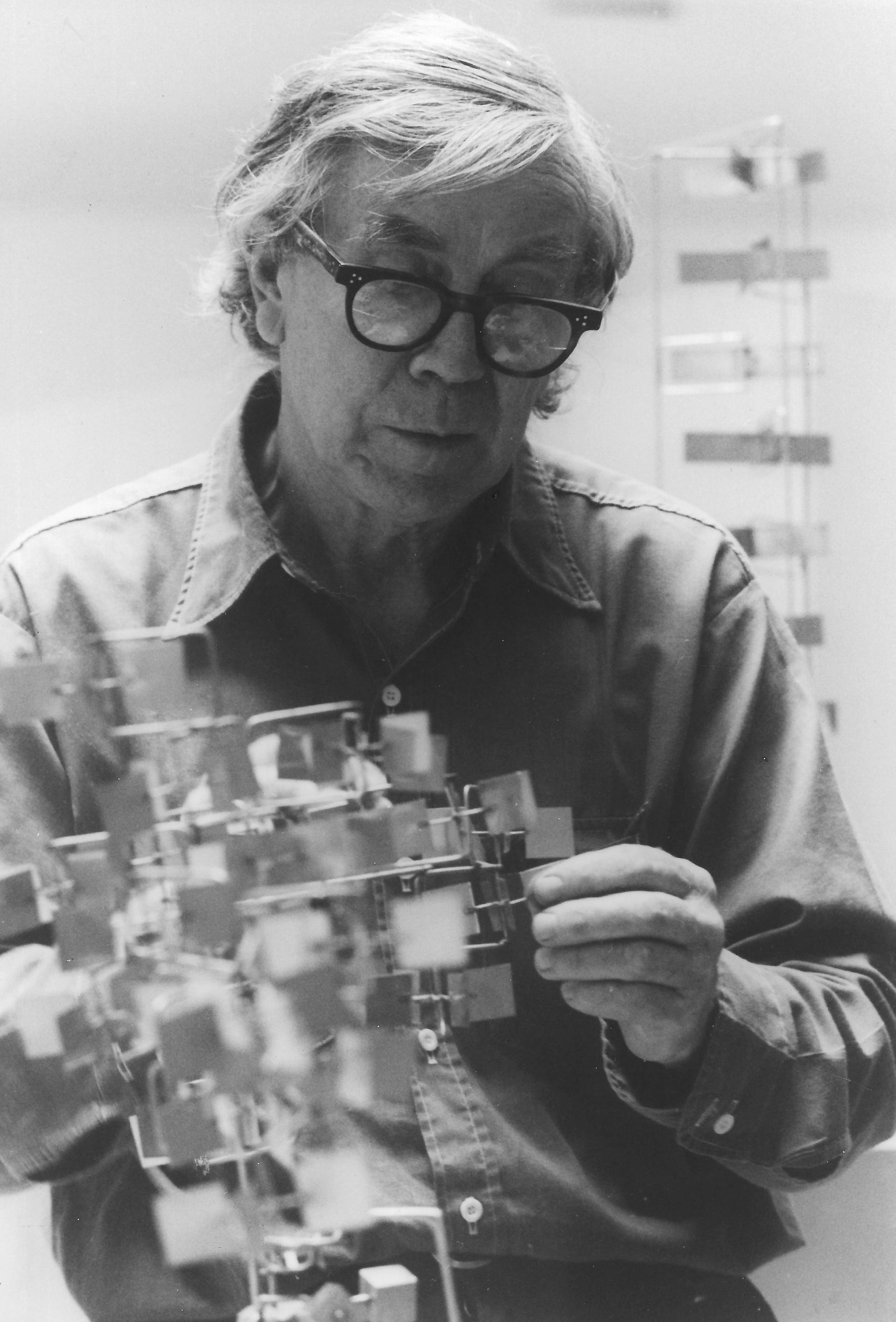

George Rickey installs Study for Crucifera IV at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, September 1979 Photo: Achim Pahle © George Rickey Foundation, Inc

The Park Avenue show will include Two Red Lines, Rickey's first monumental sculpture made in 1963, with two 32-foot-long blades pivoting on knife-edge bearings (in 1975 he updated the mechanism with ball bearings and shock absorbers). The lineup of works—employing dynamic geometric compositions of lines and planes, rectangles and triangles—will show how he progressed from simple hinge forms to gyroscopic and jointed forms of movement.

“If a Rickey's outdoors, you don't need a power source,” says the son. “It just goes.”