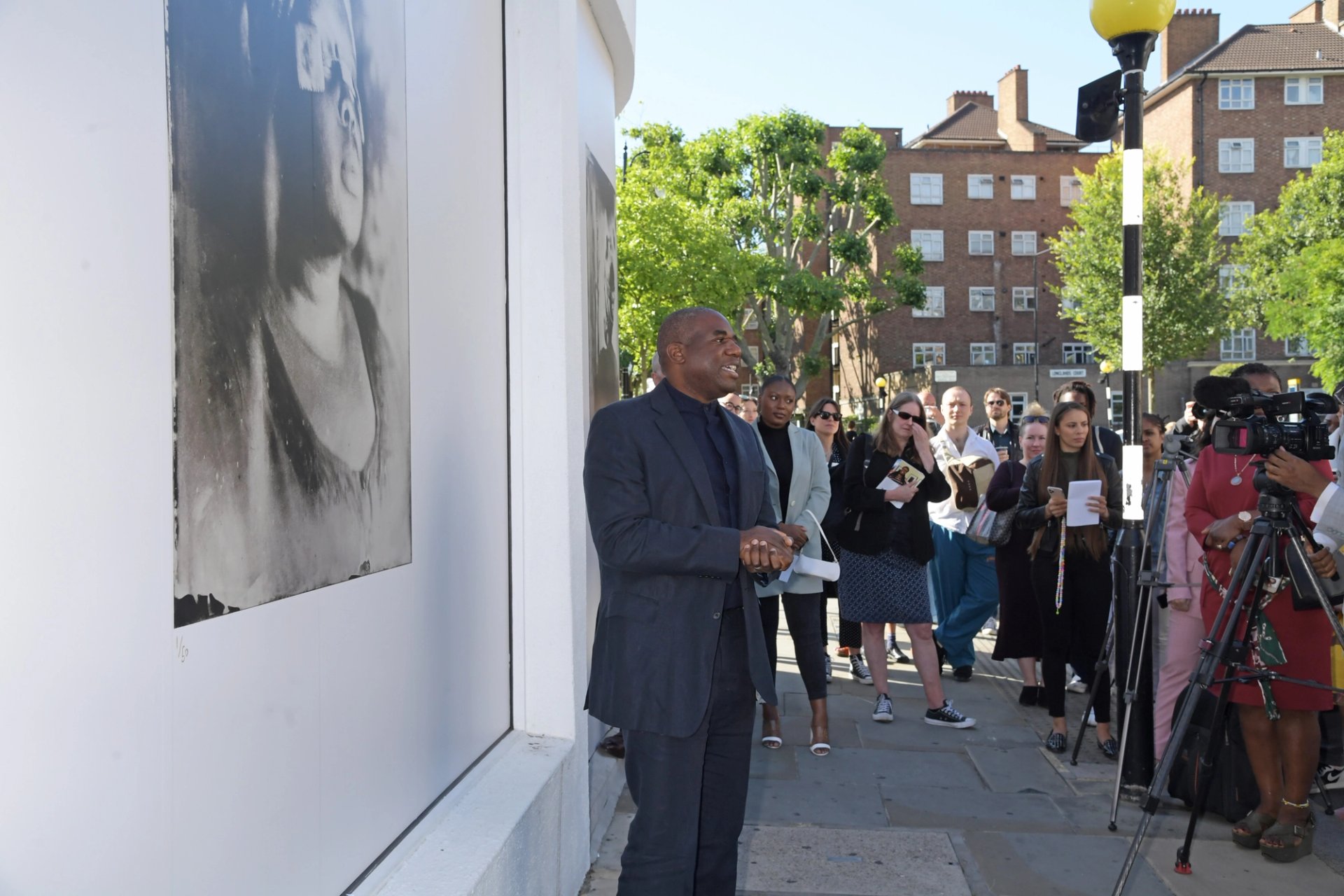

The British MP and shadow justice secretary, David Lammy, and the mayor of Kensington and Chelsea, Gerard Hargreaves, were among those gathered in west London to mark the unveiling of In This Space We Breathe, an installation reproducing the works of Khadija Saye, the young British-Gambian artist who died in the Grenfell Tower fire in 2017.

Described by Lammy, who knew her personally, as a “tender, gentle and creative soul”, the politician said Saye was “on the cusp of something special” in her artistic career when her life was tragically cut short three years ago. Saye was just 24 when she died and the majority of her work was lost in the fire.

The nine poster-sized prints have been installed along the facade of 236 Westbourne Grove, an affluent postcode just over a mile from the site of Grenfell Tower. The works were originally created as nine palm-sized unique tintypes for Saye’s first major international exhibition in the Diaspora Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2017. Six went on show in Venice; the other three were destroyed in the Grenfell fire.

British MP for Tottenham, David Lammy, described Khadija Saye as a “tender, gentle and creative soul” at the unveiling © Photo by David M. Benett/Dave Benett/Getty Images for Eiesha Bharti Pasricha

The exhibition is “very much a response to the issues of inequality, racism and injustice” that have been reignited by the global Black Lives Matter protests, according to the exhibition’s curator, Sigrid Kirk. “I felt very strongly that we had to act and not just virtue signal.”

The unveiling of In This Space We Breathe also marks the official launch of the Khadija Saye IntoArts Programme, established by the artist and wife of David Lammy, Nicola Green, who employed Saye as a studio assistant and is now the administrator of the Khadija Saye estate.

The new project is operating under the umbrella of the IntoUniversity scheme, which Saye herself attended from the age of seven, benefiting from its academic support as well as the Carnival Arts Programme. “Khadija reminded me of me,” Lammy says. “She was bright. She got a scholarship to Rugby [School], she was able to pursue her dreams of photography. In black communities that can be a struggle with your parents, because they’re worried, they know that getting a job and making a living is going to be tough. And they want you to become a doctor or a lawyer or something established.”

The Khadija Saye IntoArts Programme will introduce arts-focused activities to the IntoUniversity community learning centres across the county as well as mentoring schemes that will enable children to learn about potential careers in the cultural sector. “Speaking as a white person we often find it very hard to understand the support systems we have from childhood that we take for granted, and the opportunities that they bring to us. Khadija had to find those networks for herself,” Green says.

Khadija Saye, Peitaw (2017) © Image courtesy of the Estate of Khadija Saye

Fifty portfolio sets of the nine images currently on show on Westbourne Grove are being sold, with half the proceeds going to the Khadija Saye IntoArts Programme and the rest to the artist’s estate. One of these silkscreens, titled Sothiou, was originally made in 2017 from the unique tintype by Saye herself in collaboration with Green’s studio and Matthew Rich at Jealous Gallery.

The other eight images in the portfolio were created posthumously using salvaged high-resolution raw scans and printed by Rich “using the exact same processes and materials used for Sothiou”, Green says.

So far, 12 sets of the 50 silkscreen portfolio sets have been sold to a mixture of private collectors and institutions including the British Museum, the British Library and the Government Art Collection. Sets are available through Victoria Miro gallery, priced at £15,000 and rising to £20,000 after half the edition of 50 are sold.

Khadija Saye, Andichurai (2017) © Image courtesy of the Estate of Khadija Saye

Saye’s exhibition is the first of three public installations under the umbrella title, Breath is Invisible, curated by local resident Sigrid Kirk on the exterior of the empty Westbourne Grove building, which is owned by the entrepreneur and local resident Eiesha Bharti Pasricha. The other two shows will feature works by the musician and producer, Martyn Ware, of Human League fame, and Joy Gregory, who exhibited in the Diaspora Pavilion alongside Saye and Green in 2017.

Other community partners include West London’s Amplify Studios and The Harrow Club, who work with young creatives and arts organisations in the area.

Saye’s nine poster-sized images are greatly enlarged in contrast to the intimate scale tintypes from which they are taken, but Kirk wants the exhibition to “instigate projects and inspire children by having work in a public space while museums are closed”. She adds: “Not everyone feels museums are for them.”

Lammy likewise wants both the public installation and the Khadija Saye IntoArts Programme to open doors for as many young people from diverse backgrounds as possible. “It is our deep hope that there will be many many hundreds of Khadijas in the years to come,” he says. “I hope that the eight- or nine-year old who walks past in the next few months steps back, breathes and is inspired.”