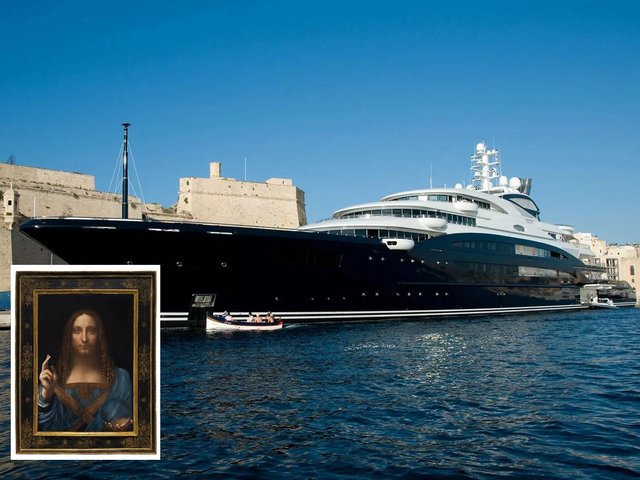

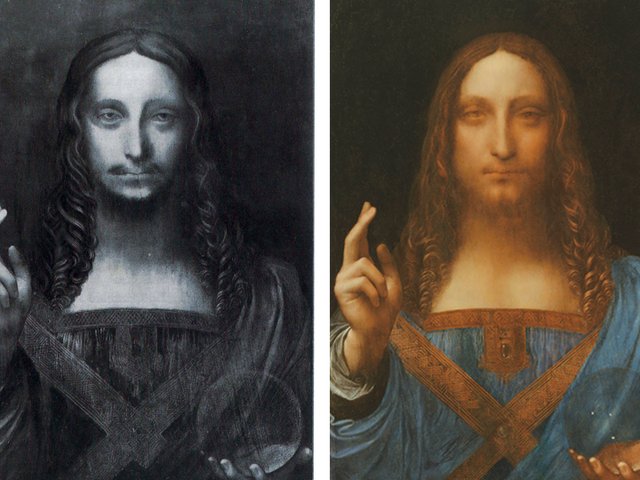

The sale of Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi for $450m (including fees) at Christie’s New York on 15 November shattered every record for art prices. Since then, speculation about the identity of the buyer has ranged from Chinese billionaires to the Microsoft co-founder and Leonardo Codex collector Bill Gates; from French government officials for Abu Dhabi to the Qatari royal family and even, among conspiracy theorists in the darker corners of the internet, President Vladimir Putin.

One less fantastical suggestion is that the buyer is Ken Griffin, who set up the global investment firm Citadel. Multiple sources suggest that Griffin planned to lend or donate the work to the Art Institute of Chicago. In 2016, he lent the museum a painting by Jackson Pollock and another by Willem de Kooning, having bought the pair for around $500m from the music mogul David Geffen. Griffin and the Art Institute both declined to comment.

The Salvator Mundi’s inclusion in a post-war and contemporary art sale was a gamble, albeit one that paid off handsomely. To minimise its risk, the auction house found a third party willing to “guarantee” the work. In other words, the painting was pre-sold to an undisclosed buyer for an undisclosed sum.

Another rumour is that the work was guaranteed by the three consignors of Andy Warhol’s Sixty Last Suppers (1986), which was included in the same auction and sold for $60.9m (with fees). Although the owners have not been revealed, the work is known to have belonged to the art dealer Larry Gagosian, who showed it in Abu Dhabi in 2010. (He declined to comment.)

The same rumour has it that in a so-called “double-bind guarantee”, the Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev, who was the seller of the Salvator Mundi through a family trust, in turn guaranteed Sixty Last Suppers for around $50m. Rybolovlev also declined to comment.

If true, the arrangement, whereby sellers guarantee one another’s works within the same sale (effectively stabilising the auction), is “extraordinary”, says the art-market commentator Georgina Adam, the author of Dark Side of the Boom, out this month. “I’ve never heard of it. If this type of deal is common, it’s unknown to the wider market, and it only reinforces the impression that the system of guaranteeing or pre-selling work is totally opaque. It belies the myth that auctions are transparent marketplaces,” she says.