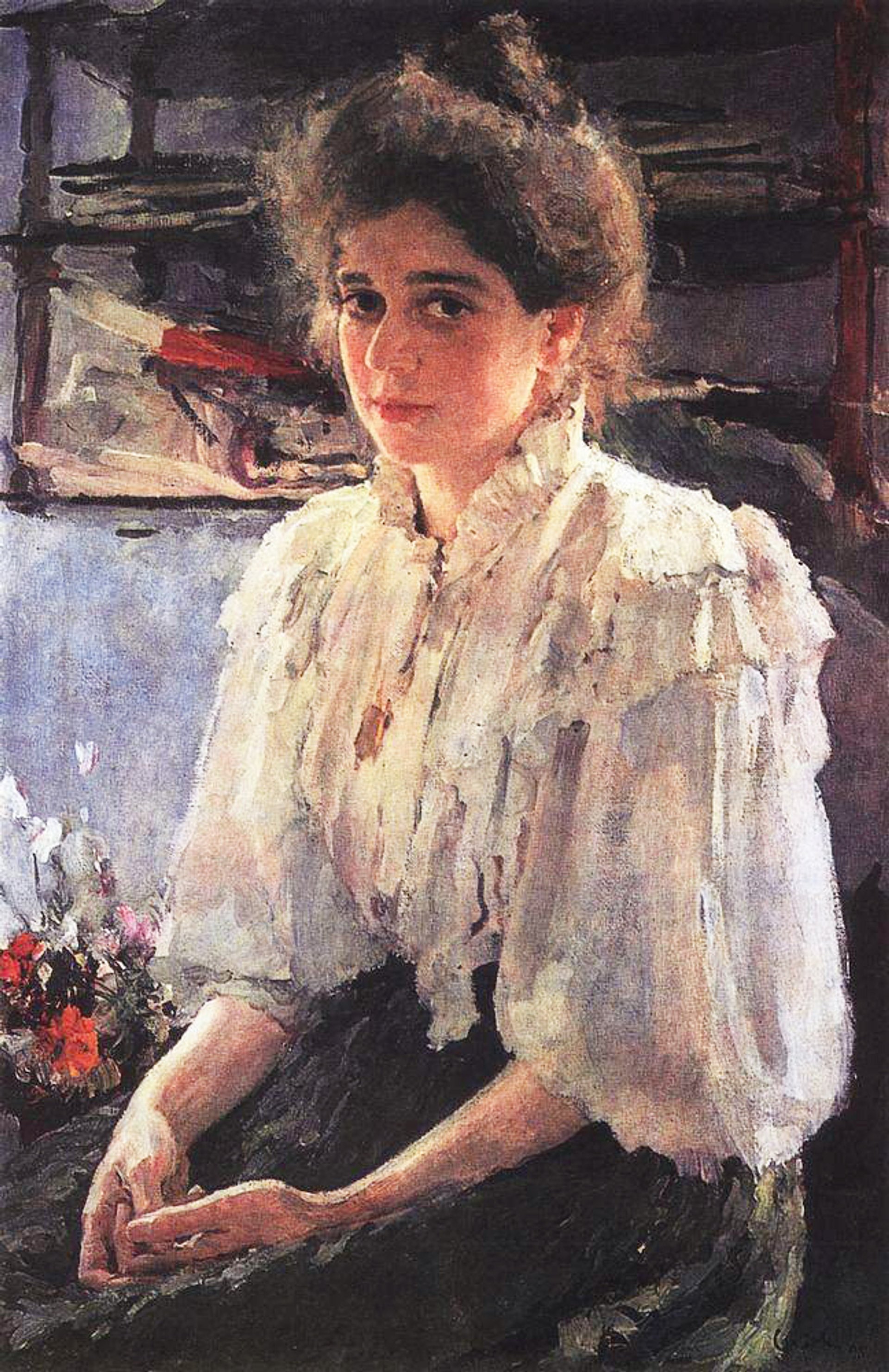

Although little known in the West, Valentin Serov—a Russian fin-de-siècle artist famous for his portraits of artists, aristocrats and tsars—is beloved in Russia. The artist’s exhibition at Moscow’s State Tretyakov Gallery marking the 150th anniversary of his birth has been drawing crowds ever since it opened in October. But even the most die-hard Serov fans will have been surprised at the passion the show inspired in Moscow museum-goers who stood in line for hours in subzero temperatures last week and quite literally beat down the doors of the museum.

Last Saturday, the museum announced that due to popular demand the show would be extended through 31 January (it had already been prolonged once before). But six works from foreign museums will be missing in the extended run, including Madame Lwoff (1895), a portrait of the artist’s cousin, from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Over 100 paintings and 150 graphic works from the Tretyakov and on loan from two dozen Russian and four foreign museums as well as private collections have been on display. A mock-up of a proscenium curtain completed by the artist in 1911 for a Ballet Russes production of Scheherazade is also on show.

Zelfira Tregulova, the general director of the Tretyakov, told reporters on Sunday that 440,000 museum-goers had already attended the Serov show, making it the most visited Tretyakov Gallery exhibition in the past half-century and possibly “an absolute record number in the history of exhibitions in the USSR and Russia.”

The more caustic commentators credited a visit by President Vladimir Putin on 18 January for drawing a new wave of Serov lovers. He was shown on state television touring the exhibition with Tregulova and Vladimir Medinsky, Russia’s culture minister, and commenting on Serov with detailed knowledge of the artist’s childhood. He also discussed a popular internet meme that was inspired by the exhibition’s popularity. Putin, viewing Serov’s paintings of Alexander III and Nicholas II, compared Serov to Diego Velázquez, the Spanish court painter.

Serov, however, had complicated relations with the Russian court. He had artistic differences with Empress Alexandra over a portrait of Nicholas II and quit the Imperial Academy of Arts after Tsarist forces shot demonstrators on Bloody Sunday in 1905.

As crowds swelled at the Tretyakov, angry Facebook posts accused the museum of failing to honor e-tickets that the museum had urged visitors to buy as a way of bypassing the line. Despite extended museum hours, tempers flared to such an extent after the near-storming of the museum on 21 January that the Russian Military-Historical Society, an organisation run by Medinsky, set up tents to feed those in line with buckwheat kasha and warm them with tea.

The Tretyakov has promised to work out new crowd-control procedures for future exhibitions. The State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts is already working on a system of timed visits to popular exhibitions, according to a report on the Moscow city government’s website.

While crowds have tapered off at little at the Tretyakov this week, commentators are still analysing the deeper meaning of the long lines.

Maxim Trudolyubov, the comments editor of the business newspaper Vedomosti, wrote on Facebook—as did many—that the lure of Serov is in the search for Russian identity. “The Russian people have an identity deficit,” he wrote.

Dmitry Bykov, a poet and social commentator, had a much simpler take on the Russian psyche: “Seeing any line, our people will go and stand in it.”