A 15th-century Persian Quran manuscript quietly made a big new auction record for an Islamic manuscript when it sold in June at Christie’s London for £7m (with fees), ten times the estimate and almost double the previous £3.7m record for a Quran, achieved at Christie’s London last year. Sources suggest that the Quran may be destined for Saudi Arabia, but Christie’s declined to comment.

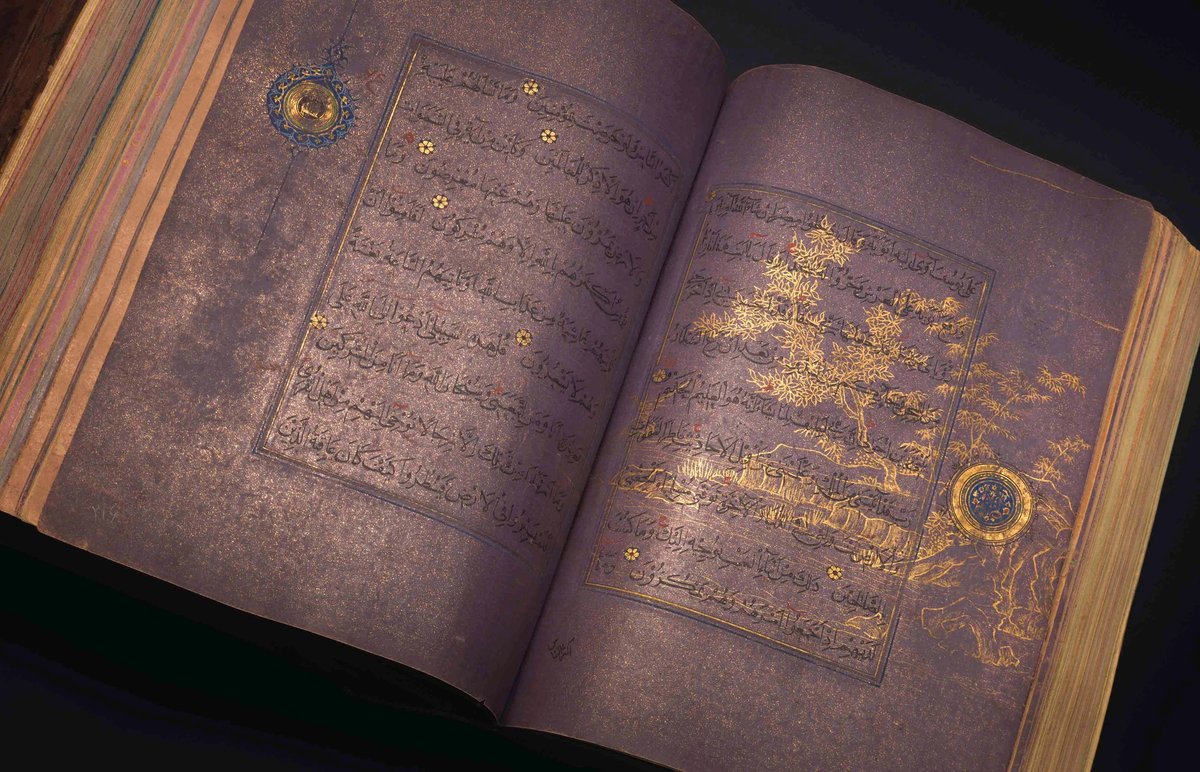

The manuscript was probably created at the court of a Timurid prince in what is now Iran or Afghanistan, and contains 534 richly coloured, gold-flecked pages of Chinese paper covered in Arabic calligraphy. It was estimated to sell for between £600,000 and £900,000 at Christie’s Art of the Islamic and Indian Worlds sale.

But Yael Rice, the assistant professor of art and the history of art and of Asian languages and civilisations at Amherst College, Massachusetts, and Stephennie Mulder, the associate professor of Islamic art and architecture at the University of Texas at Austin, say the manuscript has a “‘no provenance’ provenance” as its known ownership history only dates back to the 1980s.

They point to their email to the department of Islamic and Indian art at Christie’s, which provided the information that the Quran was bought by the current vendor’s father in London in the 1980s. “Transparency about provenance ensures that the purchase of an object is not in violation of the 1954 Hague Convention or the 1970 Unesco Convention,” Rice and Mulder say. “Since this object apparently has no provenance prior to the 1980s, we can’t know anything about the context in which it was removed from its country of origin.”

It is not a legal requirement that an item of cultural heritage must have a provenance traceable back to before 1970, though it is desirable. In response to Rice and Mulder's claims, a Christie’s spokeswoman says the Qur’an manuscript has been in the same collection for 40 years: “As included in the catalogue notes, a number of additional pages of this manuscript were made in the 19th century, likely in Central Asia. The paper of the manuscript was made in China in the late 14th or early 15th century and most pages of the manuscript were written in Persia in the 15th century. Manuscripts have historically been very personal and portable objects, frequently travelling with people across borders through time.”

She adds: “It is hugely important to establish recent ownership and legal right to sell. Christie’s will not sell any work of art that we know or have reason to believe has been stolen or illegally exported from its country of origin."

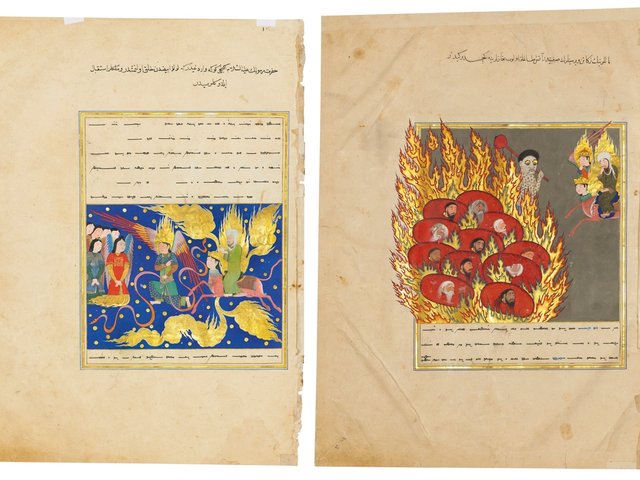

Manuscripts, Rice and Mulder say, “often get less attention than other forms of endangered cultural heritage like archaeological sites” despite their historical significance. The "dismemberment of manuscripts for profit and the lack of complete provenance impedes our ability to reconstruct and interpret the past" they say, pointing to the contentious sale of two illuminated pages from another 15th-century Timurid manuscript at Christie’s last October.