Reading the 899 pages of Eva Hesse’s diaries from the 1950s and 1960s, which have been excerpted but never published in full until now, feels like eavesdropping on a young, ambitious woman’s psychotherapy sessions. While struggling to make great work, the late German-born, US-raised artist confesses to attacks of self-doubt and anxiety, acute fears of abandonment and, on occasion, fears of getting fat. She tracks her moods, winter colds, her PMS and the disintegration of her brief marriage to the sculptor Tom Doyle. Inspired, no doubt, by her ongoing therapy sessions, she also records her dreams. In her nightmares, a German shepherd and Nazi-like officers chase after her.

Given their use as therapeutic tool, the diaries give an intimate but radically incomplete view of Hesse—one that makes her seem forever stymied as an artist. (When she is working, she is not writing as much.) The startlingly original, fragile-but-powerful sculptures and drawings that made her the subject of celebrated posthumous surveys (from the Whitechapel Gallery in London to the Guggenheim in New York and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among others) hardly even figure in the entries apart from an occasional shopping list, like: “2 wires + weights + tape + thin foam rubber”.

Yet the publication of the diaries (in spell-corrected but otherwise unaltered form, says the editor Barry Rosen) is a welcome event, offering a portrait of a young artist determined to take a seat at a male-dominated table—or a spot in their shows. The book benefits from being read alongside a new documentary, now showing at Film Forum in New York, by Marcie Begleiter, who draws on Hesse’s diaries and correspondence as well as new interviews (with Nancy Holt, Sylvia and Robert Mangold and Lucy Lippard, among others). Together, the book and film show how, despite and because of her anxiety, Hesse made profoundly eccentric, often self-repeating, sculptures—by turns prickly, lumpy and loopy—that both speak to and stand apart from standard minimalist art of the 1960s.

The film and journals cover some familiar ground: her travel by Kindertransport out of Nazi Germany to a detention centre in Amsterdam, aged two, her bipolar mother’s death by suicide when she was almost 10 and the brain tumour that killed her, aged 34, in 1970. But beyond these dramatic bookend moments, the book and film provide some new insight into the central relationships and preoccupations of Hesse’s life—which is, perhaps inescapably, part of how we read her art. Here are four of the most interesting discoveries.

Behind one powerful woman is another powerful woman While the support from some big (male) guns of minimalism like Mel Bochner and Sol LeWitt certainly helped advance Hesse’s reputation, feminist critics starting with Lippard have worked tirelessly to carve out a place for her in 20th-century art history. But working more quietly behind the scenes, without art history expertise, is Eva’s older sister, Helen Hesse Charash, now in her 80s. She is the one who held Eva’s hand when they took the Kindertransport train out of Nazi Germany and has long overseen the estate, represented by Hauser & Wirth. Her appearances in the documentary show just how thoughtful Hesse Charash has been with her younger sister’s legacy, starting with a clip in which she handily dispels the myth of the artist as a tragic, 19th-century-style heroine. “There were times she felt helpless, but she had gutsiness right from the get-go,” Hesse Charash says. All great artists should be so fortunate to be remembered with complexity and clarity both.

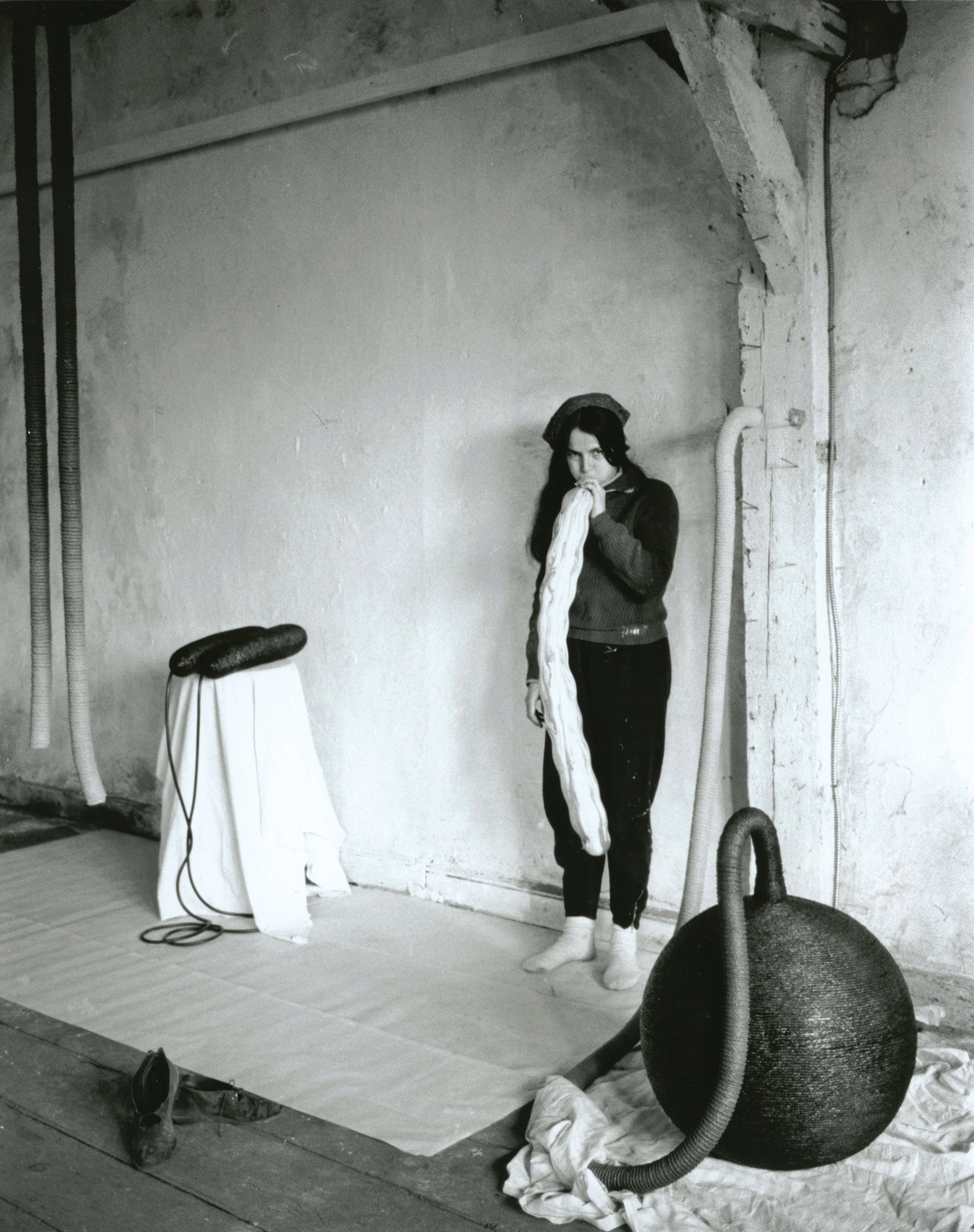

Hesse’s marriage to Tom Doyle was violent Many critics identify Hesse’s painful stay in Kessig, Germany in 1964-65 with her new husband, the sculptor Tom Doyle, as a seminal period. During this time, she is said to have grown from a painter into a sculptor, literally picking up ropes off the floor of the studio—a former weaving factory—to make new work. The standard story also describes how the implosion of her turbulent marriage caused a redoubling of her own sense of purpose at work. The journals make it clear there was physical violence as well. He broke a wooden bed frame. He pushed and shoved. And on October 19 1964, he poked her eye. “[P]ain terrible. The under lid of my upper lid is hurt and I feel emotionally depleted. How wasted these times are for me. And if only they would not recur,” she writes. Doyle appears in the film briefly and sheepishly chalks up their rough relationship to his drinking. “Our private life was not so great, but our working life was very good. Except I drank a little too much then, you know, I was drinking a lot, and that wasn’t so good.” Hesse Charash, her sister, says in the film: “She always says, it’s art that pulled her through. Personally, I think she fell apart, and professionally she forced herself to go on.”

“Eva was the love of Sol LeWitt’s life” LeWitt’s admiration of Hesse is well documented, and the two are the subject of a powerful travelling exhibition exploring their mutual influence, now at the Cleveland Museum of Art (Converging Lines, until 31 July). But one of the most memorable accounts of their relationship comes from an interview with the artist Carl Andre in the new documentary. “Eva was the love of Sol LeWitt’s life, and Eva loved Sol,” Andre says. “I once asked Eva, ‘You know, Sol’s a great guy, a great artist, and he loves you. Why don’t you…?’ She said: ‘You don’t go to bed with your brother.’” Hesse’s journals back up this point. In 1966, she writes: “Sol gave it to me today. He wants more than our closeness; he wants total, complete relationship. I can’t blame him, but I can neither help him. I cannot give him what he wants.”

The idea that Hesse was killed by her own art is speculation As artists learned more about carcinogens, many of Hesse’s friends advanced the idea that her hands-on work with fibreglass and resin could have caused her brain tumour. The film plays out both sides, with Lippard describing her intimate relationship to these materials and how she “was probably breathing them and tasting them”. Hesse’s studio assistant and fabricator Doug Johns, of Aegis Reinforced Plastics, counters: “This is the beginning of fibreglass, but it really is not that toxic and her tumour was far too large to even think that that small amount of exposure that she had gave her that brain tumour.”

While neither side has real evidence to back up their convictions, the debate reminds us to stay away from blanket statements that Hesse’s cancer was caused by her art, which serves in some hands to feed the myth of a vulnerable female artist. Worse yet was the time in the 1970s when Hesse was lumped in with Sylvia Plath and Diane Arbus as though she had committed suicide. The diaries also put this to rest: even during the worst of her marriage, she did not have suicidal tendencies, but rather a strong urge to defend herself—and to create.

• Eva Hesse: Diaries (edited by Barry Rosen), Yale University Press and Hauser & Wirth, May 2016. $45; Eva Hesse (directed by Marcie Begleiter), theatrical debut at Film Forum, New York (until 10 May) and Laemmle Monica Film Center in Santa Monica on 13 May