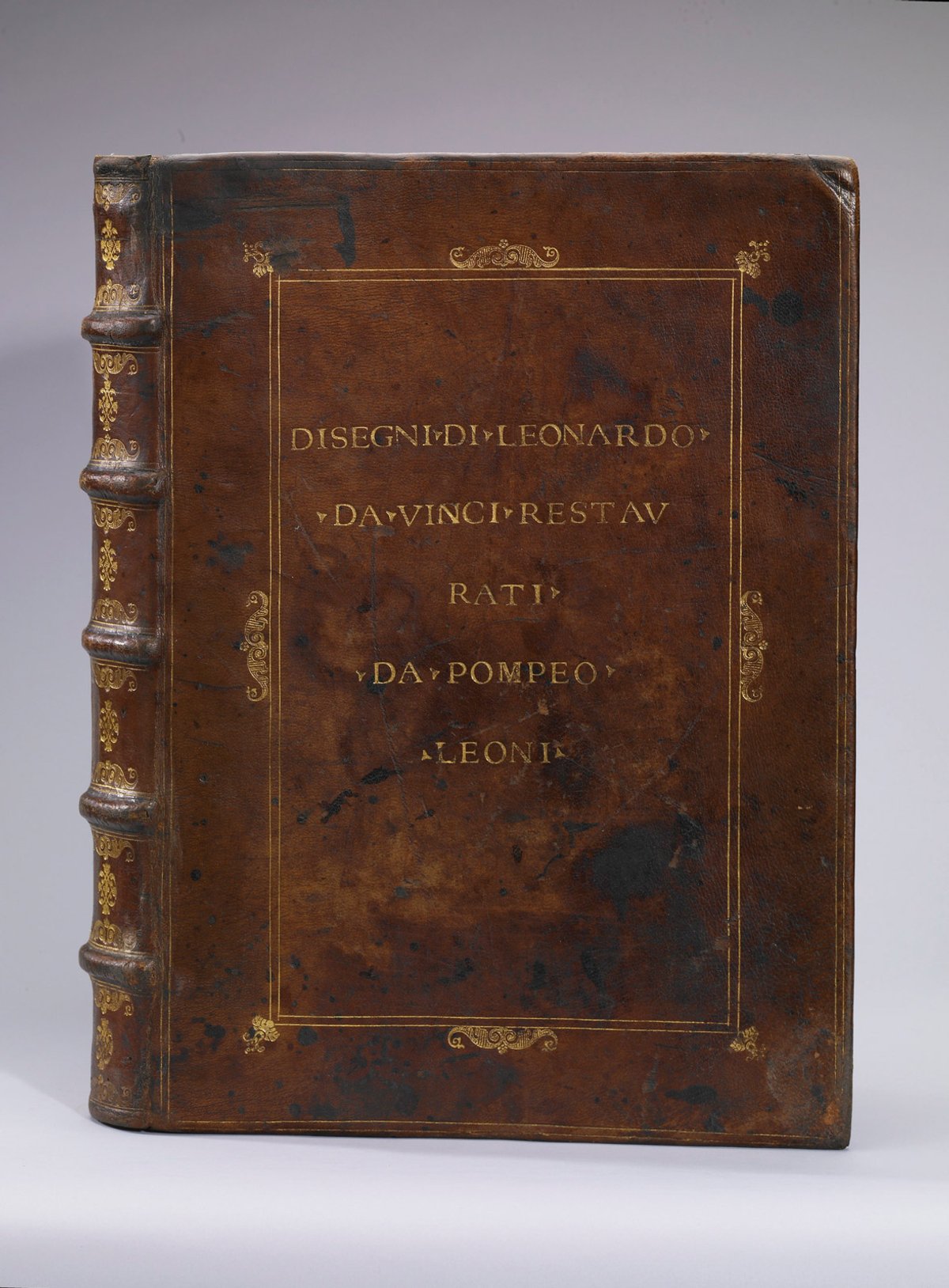

Were the wonderful Leonardo drawings at Windsor once owned by Charles II? Scholars have been intrigued by the idea, but there has been no proof. Their earliest documentation in the Royal Collection dates from 1690, when Constantijn Huygens Jr, secretary to William III, spent a morning leafing through the bound album. So, when I stumbled on a report in an English publication of 1680, it was not so much “eureka!” as “gotcha!”. Here, unmistakably, was an eyewitness account of Leonardo’s drawings being in Charles II’s Whitehall Cabinet.

The testimony came from a blue-chip source—Walter Charleton (1619-1707), physician-in-ordinary to Charles I and Charles II. Prominent in his own day, he is now eclipsed by more famous friends, John Evelyn, Anthony Wood and Margaret Cavendish. In March 1679, as Harveian Orator of the Royal College of Physicians, Charleton gave the inaugural lectures in the new anatomy theatre. These were published in 1680 as Enquiries Into Human Nature: in VI. Anatomic Praelections in the New Theatre of the Royal Colledge of Physicians in London. The opening words of the sixth lecture, “Of motion voluntary”, are startling:

“For Painting, I recommend to them the incomparable Lionardo da Vinci, della Pittura: not only because he was eminently skill’d in all parts of Anatomy, as appears by the accurate Figures that illustrate and adorn Vesalius’s noble Volume De Corporis humani fabrica, all of which were drawn and cut by Da Vinci’s own hands; and the original Draughts of which are yet extant in a large Manuscript of his in Folio, in the Italian language (but written from the right hand to the left) carefully preserv’d in His Majesties Cabinet at White-Hall, where I have had the good fortune sometimes to contemplate them: but also because in his Treatise Della Pittura just now mention’d, he seems to me to have describ’d the figures, motions, forces and symmetry of the limbs, their Articulations and Muscles, in various postures, more clearly than any Writer I have hitherto read.”

Charleton’s intimate contact with the Leoni-Leonardo album is palpable, and felicitous; we could scarcely conjure a more fitting 17th-century English reader. Discussing Leonardo’s writings on animal and human musculature, he cites a passage in the editio princeps (Paris, 1651) of the artist’s Trattato della pittura. To identify a text that confirms Charles II’s ownership of the album during the 1670s connects Leonardo’s anatomy drawings and the treatise on painting, and situates them in the frontline of 17th-century scientific theory, was, for a Leonardo nerd like me, equivalent to finding the missing evolutionary link. The new discovery holds out the promise of further “eureka” moments among the papers of Charleton’s networks, and a glimmer of hope that we may yet ascertain how Leonardo’s celebrated drawings entered the Royal Collection.

• Margaret Dalivalle’s discovery is discussed in more detail in Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi and the Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts, published on 17 October by Oxford University Press. She teaches at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Oxford