In the sleepy borough of Madison, New Jersey, the trustees of a foundation have found a major lost work by the French sculptor Auguste Rodin. The marble bust of Napoléon Bonaparte (from around 1908), which experts had lost track of in the late 1920s, had been sitting in a town hall committee room. After being authenticated by a Rodin expert, the work is due to go on loan to the Philadelphia Museum of Art by the end of October, in time for the centenary of the artist’s death next month.

Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge is the key to how the sculpture arrived in Madison. The daughter of William D. Rockefeller and an avid art collector, she provided the funds for the Neo-Classical Hartley Dodge Memorial Building, erected in 1935 and named after her son, who had died in a car accident. According to recent research done by the foundation that oversees the preservation of the historic town hall, she had acquired Rodin’s bust at auction the year before from the family of Thomas Fortune Ryan, a tobacco magnate, who had loaned it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from 1915 to 1929.

Dodge, who lived on a 300-acre estate in Madison, decorated the government building with works from her personal collection. “She was always bringing things in the building, and evidently this was one of them,” explains Nicolas Platt, the president of the Hartley Dodge Foundation. “But there was no paper work.”

Consequently, the Napoleon fell into obscurity. For around eight decades, the imperial bust silently gazed down from a plinth in the building's main committee room, scarcely noticed by local legislators or passersby. It was not until 2015, when the foundation hired an archivist, a 22-year-old graduate student named Mallory Mortillaro, that the sculpture’s full provenance came to light. “She was running her finger along the base,” Platt says, “and felt a chiseled mark, and got a flashlight, got on a chair and peered over, and there was the signature of A. Rodin.”

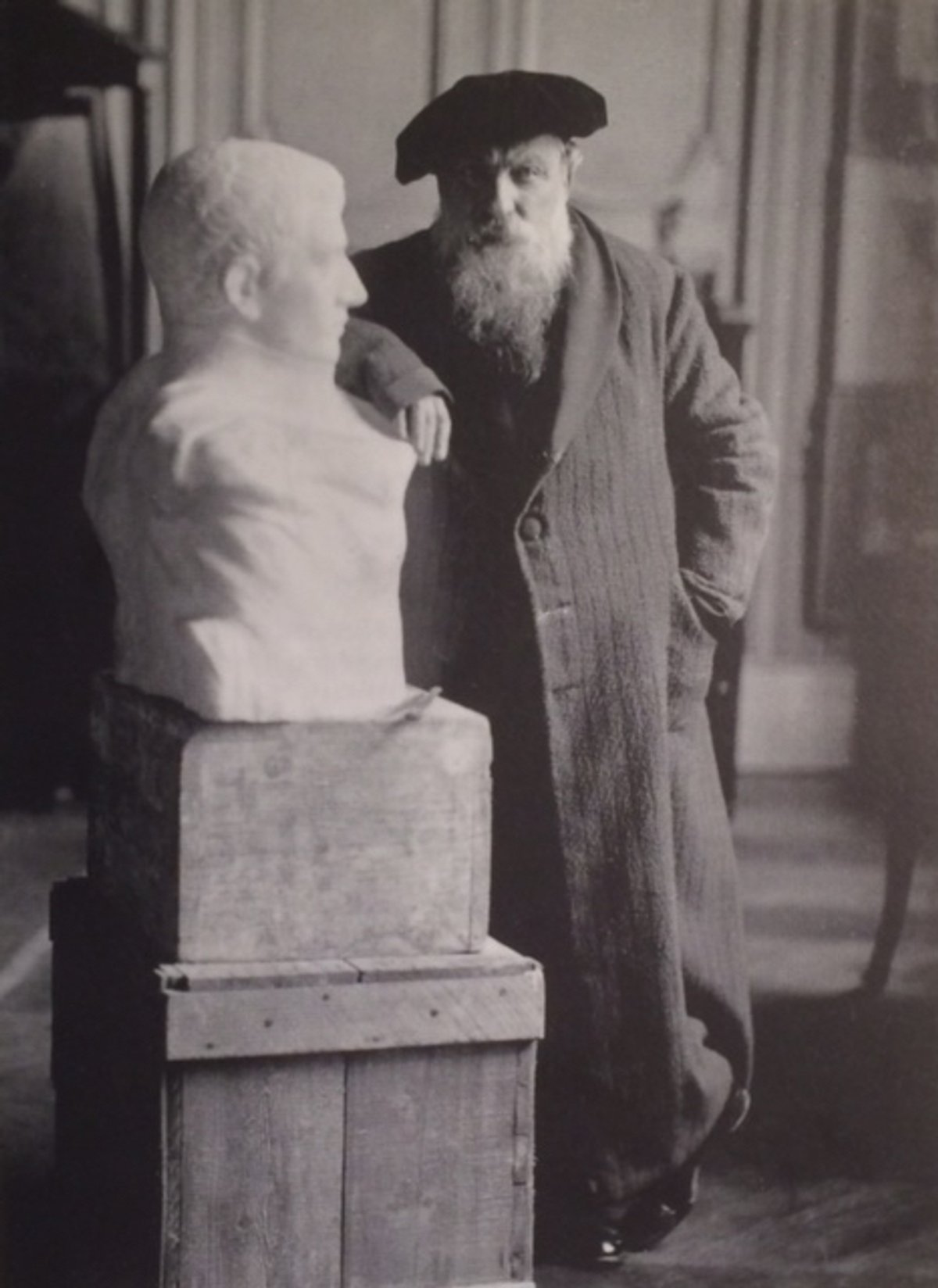

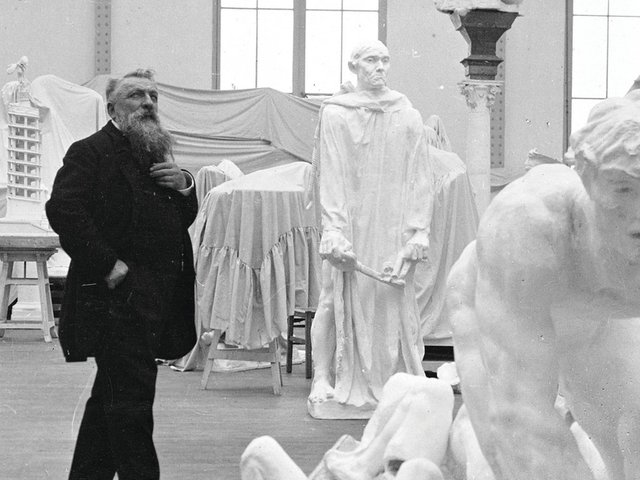

The foundation contacted the noted Rodin specialist Jérôme Le Blay, formerly of the Musée Rodin and the founder of the Comité Rodin, which authenticates the sculptor’s work. “The first pictures that they sent me by email immediately struck me,” Le Blay says over email. “We have a huge database and archives and it was rather easy for us to find the origins of this marble in the workshop of Rodin.” A photograph from 1910 even shows the sculptor posing next to the 700-pound bust, officially titled Napoleon enveloppé dans ses réves (Napoleon wrapped in his dreams).

The foundation did not announce that they possessed a sculpture estimated to be worth between $4m to $12m until this week due to security concerns. An insurance company had cautioned that such an expensive work of art could not remain in a municipal building. They contacted museums that might wish to have it on loan, and two weeks ago, the Philadelphia Museum of Art agreed. “That’s why the foundation took a pledge of silence and didn’t tell anybody [until now],” Platt says.