Do not expect a snapshot, thesis or panorama of today’s Italian art scene in the national pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale—but be prepared for a view of the fantastical. “I think a platform like the Biennale should be less about trying to systematise the Italian art scene and more about offering a different kind of experimental platform [for] artists,” explains Cecilia Alemani, the curator of the 2017 Italian pavilion. “It should be a space of taking risks and trying a different approach”.

The curator “did not want to create a museum display, because the pavilion is not a museum, it’s not going to work in that sense,” Alemani says. “It’s really a place to give artists carte blanche to transform the space radically and to offer the viewer an occasion to walk into the artist’s mind.”

In an effort “to do exactly the opposite” of previous presentations, such as 2015’s Codici Italia (Italian codex), which included 15 artists, Alemani’s show has a much tighter focus. The pavilion will feature the work of just three artists born in the mid-1970s to 80s—Adelita Husni-Bey, Giorgio Andreotta Calò and Robert Cuoghi—under the title Il mondo magico (the magic world).

The theme is taken from the title of a book written during the Second World War by the Italian anthropologist and philosopher Ernesto de Martino, whose studies looked at why cultures and individuals use magic—“meaning rituals, mythology and new faith”, Alemandi explains—“as a tool to reaffirm [their] presence in the world when there is a crisis”.

Alemani sees the works of these three artists as “very deeply embedded with magic ritual, the fanciful and also the idea of using the imagination to read the world”. The fanciful theme also serves as a counterpoint to the slew of recent exhibitions focussing socially and politically minded works, including Okwui Enwezor’s central exhibition for the last Biennale, All the World’s Futures (although Alemani is careful to mention her respect and admiration for Enwezor, whose Documenta 11 in 2002, “changed my life”, she says).

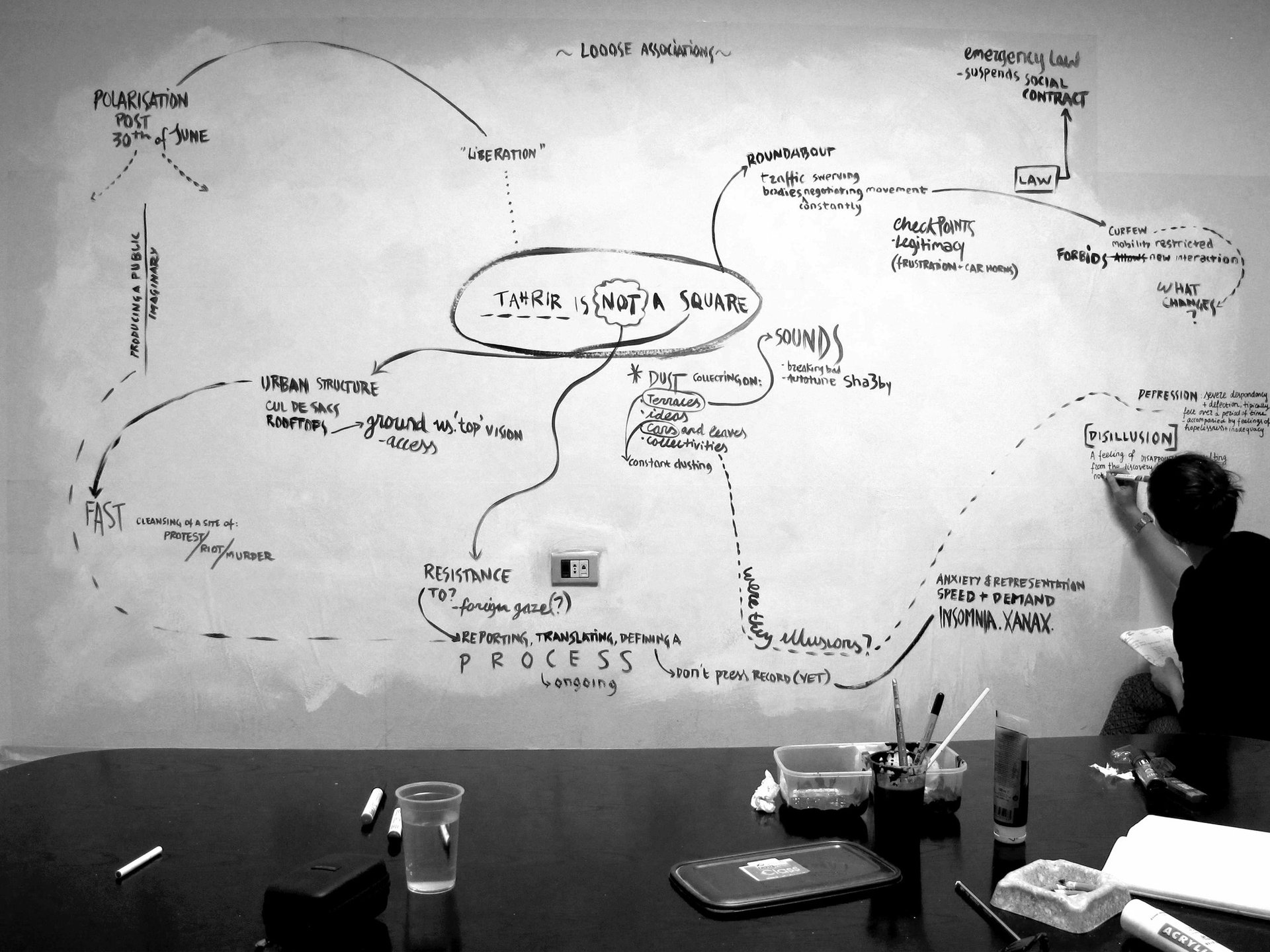

The youngest artist in the show is the Milan-born Adelita Husni-Bey, who is fascinated by “the sphere that opposes what’s rational and reasonable—not to get lost in it, but to use it as an active tool to re-imagine reality”, Alemani says. Husni-Bey organises and films community workshops that last a few days to weeks and examine topical subjects using techniques from experimental theatre and radical pedagogy. The Italian pavilion will feature a new video that is the result of a workshop the artist held with group of teens in New York, which contrasts a capitalist view of the world with one that looks at what is “impalpable or irreducible”, Alemani says.

In the work of Giorgio Andreotta Calò, a Venice native who recently moved back to the city from Amsterdam, the idea of magic includes his use of natural forces—something he shares with the Arte Povera artists, Alemani says. Water is a recurring element of Calò’s work, from flooding a studio at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Amsterdam to turning a room of Rome’s MaXXI museum into a camera obscura, with the image reflected on a pool of water. Calò is already on-site at the pavilion working on “an installation that will completely change the architecture and the way you read and see and feel the space”, Alemani says.

Roberto Cuoghi, based in Milan and the oldest and most established artist in the trio, “represents the artist as a shaman that has the ability to combine these archaic and futurist elements in his work”, Alemani says, linking him to the Italian “artist-shamans” of the 1960s, such as Alighiero Boetti and Carol Rama. Cuoghi’s work is a mix of cutting-edge technology and traditional materials—such as ceramics with unusual glazes made from proteins or 3-D printed clay works that are then fired in homemade kilns. Entering his space in the pavilion will be “like walking into the artist’s studio”, and will include a new sculptural installation, with some objects brought to Venice and some made on-site using experimental materials. “It’s not going to be a white space with five sculptures—it’s going to be messy,” Alemani promises.