France has long been accused of dragging its feet on the restitution of Nazi-era loot. According to a French government report published last year, France’s policies are characterised by “time delays” and “weak responses and inaction”. France pledged to improve research in this area at an international conference in Berlin last December and is setting up a taskforce to tackle some of these issues. But a major court case will put these assurances to the test.

The Ministry of Culture has been summoned to appear in court at the end of June by the heirs of René Gimpel, an art dealer who died in a concentration camp in 1945. His grandchildren accuse the French state museums of blocking the restitution of three paintings by André Derain since 2013.

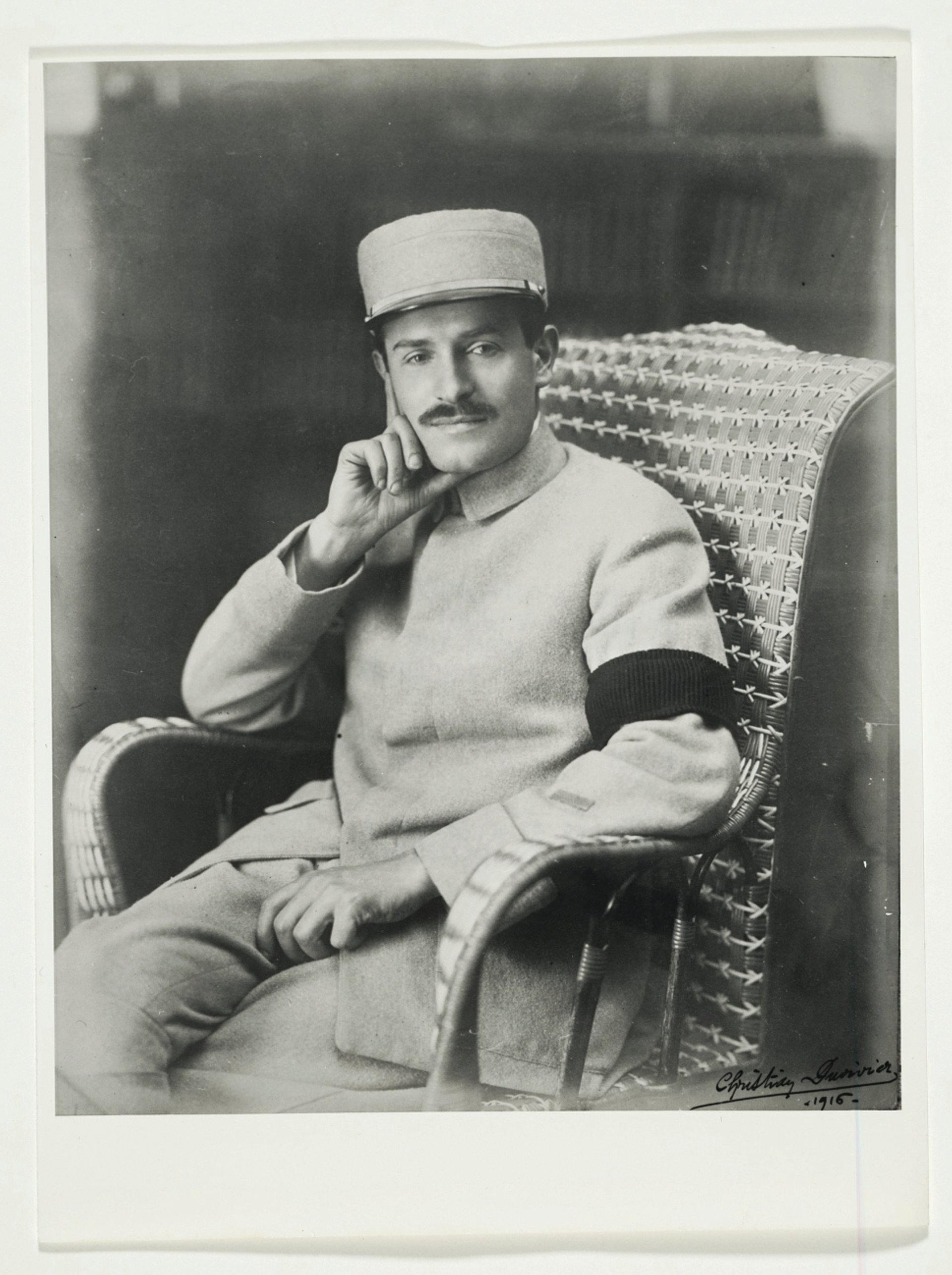

Born in 1881, Gimpel, who was related to the Wildenstein and Duveen families, became one of the most prominent art dealers of the 20th century. In 1902, his father Ernest opened the Gimpel & Wildenstein Gallery in Manhattan, selling 18th-century French and British works to collectors such as Henry Clay Frick and John D. Rockefeller. Later, when René Gimpel took over the gallery, clients included the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Gimpel also began dealing in Impressionist and Modern paintings. In 1921, he bought six works by Derain from the Kahnweiler collection at the French auction house Drouot. The works still featured in the gallery’s stock records in the early 1940s.

The Gimpel Gallery in Trouville-sur-Mer, Calvados, around 1900 Gimpel family archives/Archives of American Art; Smithsonian Institution

In 1942, Gimpel’s apartment in Paris was confiscated and looted by the German embassy, as were 82 crates of works he had placed in storage. In 1944, the Gestapo seized more of his property from a bank safe in Nice.

Involved in the Resistance with his two sons, Gimpel fled to Cannes on the Riviera, which was under Italian occupation. In order to survive and finance his underground activities—he bought a coal truck company in Marseilles to transport men and deliver messages—he was discreetly selling works. Gimpel was interned by the Vichy authorities for his activities in the Resistance, released in 1943, and then re-arrested. He was sent to the Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg, where he died in January 194.

His collection has been at the centre of several restitution claims. Derain’s Vue de Cassis (View of Cassis, 1907) was sold at Sotheby’s New York for $2.5m in 2015, and Monet’s Les Meules à Giverny (Haystacks in Giverny, 1885) from a private collection in Switzerland, was sold at Christie’s New York on 14 May 2015. In both cases, an amicable settlement was reached with Gimpel’s family. Another restitution agreement was reached on a Gainsborough, Portrait of Mrs Elizabeth Edgar, which was sold at Sotheby’s in London in December 2014 for £20,000.

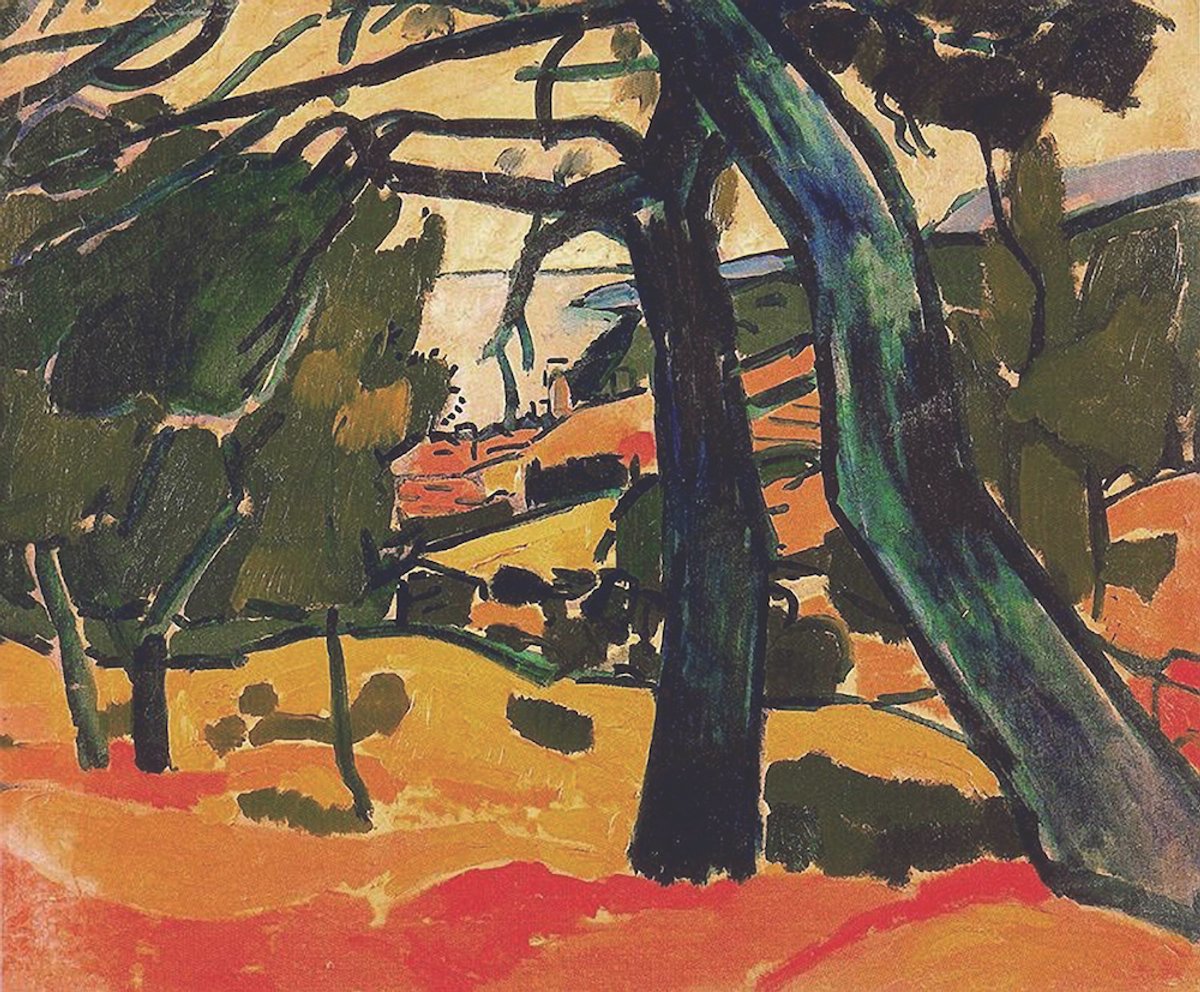

But things have not gone as smoothly with the French state. Three paintings by Derain from Gimpel’s collection, two views of the Riviera in Cassis and The Mill (1910), hang in museums in the cities of Marseilles and Troyes; the latter canvas was renamed La Chapelle-sous-Crécy. The works were connected to Gimpel by the British researcher Ian Locke a decade ago.

Corinne Hershkovitch, the Gimpel family lawyer, first met with the Ministry of Culture in 2013. It pledged to start “conducting the necessary research”, but for the next four years the family had no news. Pressed by Hershkovitch, the French state museums’ administration admitted it had no knowledge of the provenance of the two landscapes that had been donated to the Modern Art Museum in Troyes by the collector Pierre Lévy, although Gimpel’s family later discovered that he had bought at least one of them at Drouot in 1951.

A portrait of René Gimpel taken in 1916 © Succession René Gimpel

The third picture, Pinède à Cassis (Pine Landscape, 1907), was acquired in 1987 by the Cantini Museum in Marseilles from a local industrial family who had bought the picture in 1942 from an art critic. It was described as sold in Gimpel’s inventory in 1943—or, more exactly, “returned to its owner”, a necessary precaution at the time as Jewish people were prohibited from trading goods under French law.

In August 1941, in one of the cryptic postcards Gimpel sent to an assistant in Paris, he asked her to “take care of his valuable old friend Derain”. His granddaughter Claire says: “He had to use these codes. It is quite clear he needed the money she could get from the Derain paintings,” Claire transferred these documents to the ministry, but there was still no answer.

In December 2017, Hershkovitch went back to the Ministry of Culture. She received a reply requesting yet more documentation and assurances that the ministry was “actively researching the case”. Vincent Lefèvre, the deputy director of collections at the ministry, who signed the letter, tells The Art Newspaper: “These investigations take time.” But he also expressed doubts: “Gimpel’s situation was indeed difficult, but he was still dealing in art. And it is not clear if these sales were legitimate or not.” Hershkovitch, however, has no doubt that the sales were forced. “Until his arrest and deportation in 1944, Gimpel was hiding in the south of France. He could not travel to Paris and was not authorised to work. These sales were clearly made under duress,” she says.

The court case comes at the same time as the launch of a central taskforce under the prime minister’s authority to guide research and even decide on restitution cases. The entity sidelines the museums’ administration, which has historically been responsible for this issue. It will be headed by David Zivie, who authored the report that criticised the ministry’s policies. However, after a full year, the seven-member team has not yet been finalised.