If Mexican art in the inter-war years was dominated by the “tres grandes”, the megastar muralist trio of Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siquieros, then the latter part of the 20th century belonged to Francisco Toledo, the prolific painter, photographer, sculptor and textile artist who died on Thursday at the age of 79.

Toledo, referred to across Latin America as “El Maestro”, or Master, was known for work employing symbolism–insects, alligators, monkeys–rooted in his native state of Oaxaca and for an activist bent that once led him to block a McDonald’s from opening in Oaxaca’s central city.

He was one of seven siblings born in Juchitán to a family with roots in one of the many indigenous communities in the area. His aptitude for sketching a likeness was spotted when he was nine, at a time when it was considered a luxury for children to attend school, let alone study art. His shopkeeper father enrolled him at Taller de Grabados, where he studied under Arturo García Bustos and Rufino Tamayo, before he transferred to the Institute of Fine Arts in Mexico City. At 19, Toledo held his first solo exhibition in the Mexican capital, which would travel to Fort Worth, Texas.

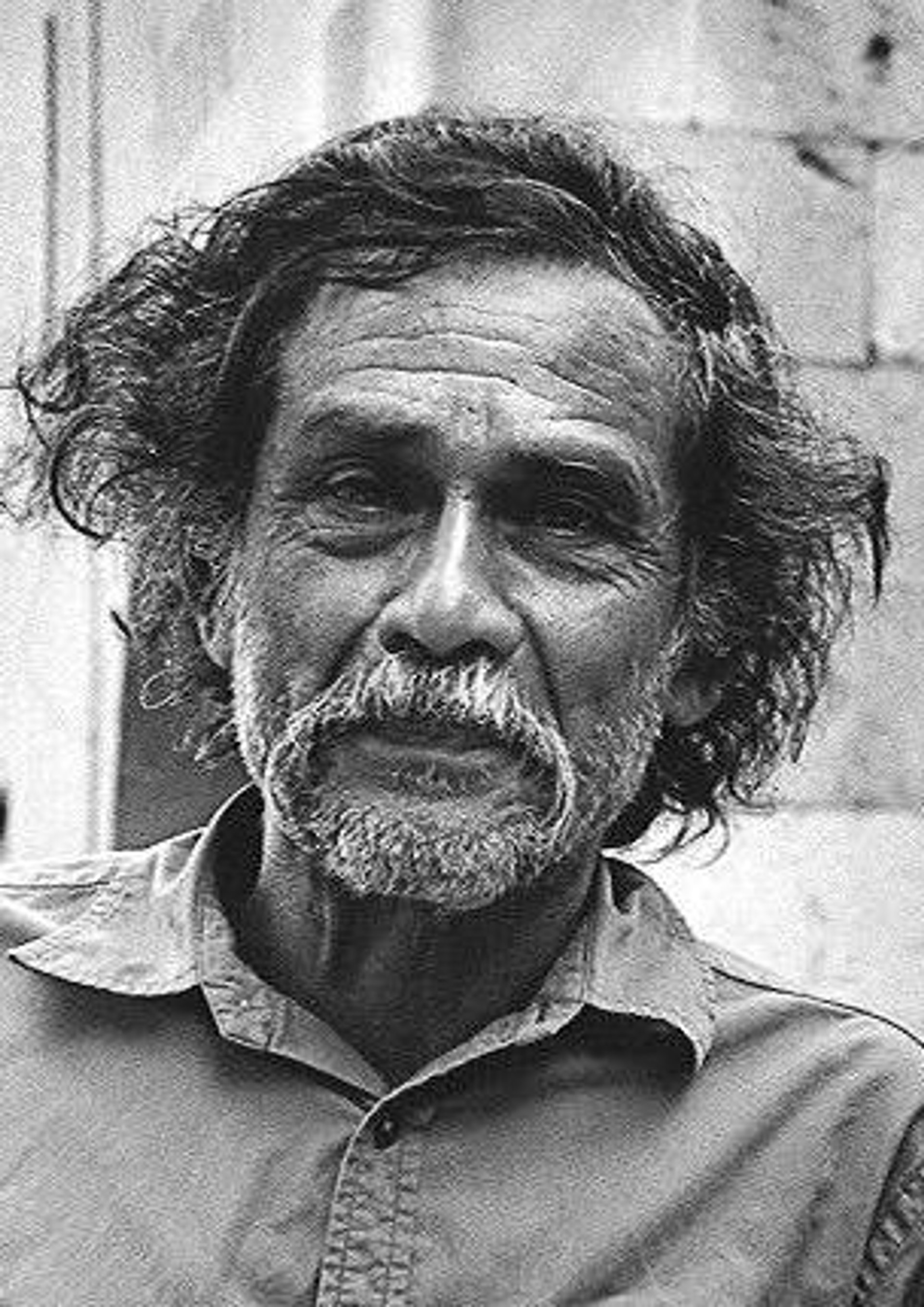

The artist Francisco Toledo

On the advice of the gallery owner Antonio Souza, who had helped arrange the Mexico City show, Toledo decided to expand his horizons and journeyed to France, where he was reunited with Tamayo and also worked in the printmaking atelier of the English engraver Stanley William Hayter. His first Paris show, in 1963, was a success but Toledo later spoke of how lonely he had been in France. By 1965 he had moved back to Mexico.

Profoundly affected by the police brutality he witnessed during the Tlatelolco student massacre in 1968, he demanded the withdrawal of his art from display in a government office. He then sold some works and sent money to the bereaved families. Returning to Oaxaca, where he moved into a relatively modest dwelling with his family, he proceeded to bankroll such cultural assets as the Institute for Graphic Arts; the Centre for Contemporary Art; three libraries, including one for the blind; and myriad other educational initiatives.

In 2002 Toledo led the campaign to prevent the opening of a McDonald’s restaurant off the historic 17th-century plaza in Oaxaca, threatening to parade naked in front of diners. The threat of nude protesters under the golden arches won the day.

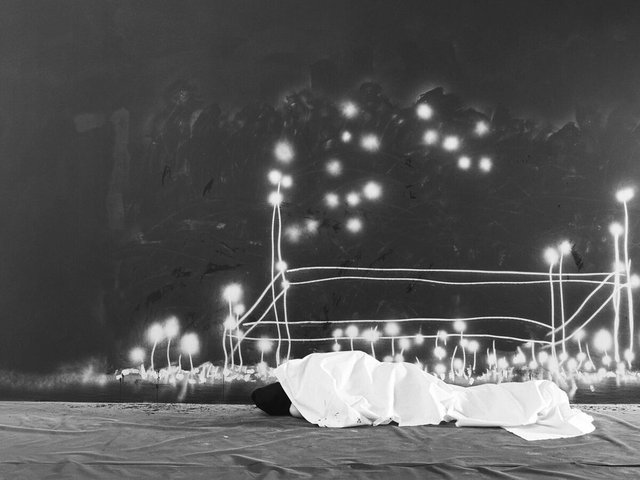

He also lent his name, as did such artists as Leonora Carrington and Tamayo, to an environmental collective established by the poet Homero Aridjis in an unsuccessful 2004 effort to halt the destruction of Cuernavaca’s Casino de la Selva to make way for two giant retail stores. And when 43 teacher trainees mysteriously disappeared while in police custody in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, in 2014, the artist created a poignant installation of paper kites, each bearing the face of one of the missing.

Toledo experimented widely. He is perhaps best known for his works on canvas, bark and paper and for his prints, but also worked with ceramics and textiles. Although his reputation outside his own country did not equal the fame he won in Mexico, he gained an international profile with exhibitions like a 2000 show at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, winning new converts to the mythical landscapes featuring the flora and fauna that he grew up with.

He is survived by his third wife, the weaver Trine Ellitsgaard, and five daughters and sons: Natalia Toledo Paz, the Mexican minister of cultural diffusion; Laureana Toledo, a photographer; Jeronimo López Ramirez, the artist and tattooist known as Dr Lakra; Sara López Ellitsgaard, head of the Institute of Graphic Arts of Oaxaca; and Benjamin López Ellitsgaard. A retrospective of his work is on view at the Museum of Popular Cultures in Mexico City until the end of September.