The Nazi leader Hermann Goering usually got the art he wanted, especially when it belonged to a Jewish collector. But one Germany’s oldest and finest medieval tapestries eluded the Nazi leader’s grasp. The German-Jewish industrialist Ottmar Strauss defied the Nazis in a quiet act of resistance, recently revealed on social media by a curator in lockdown.

The 15th-century tapestry Wild Men and Moors was recently featured in a series of tweets by Victoria Reed, the provenance curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Posting the history of a work from the collection each day online while the museum is closed during the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic was “a spur of the moment decision,” she says.

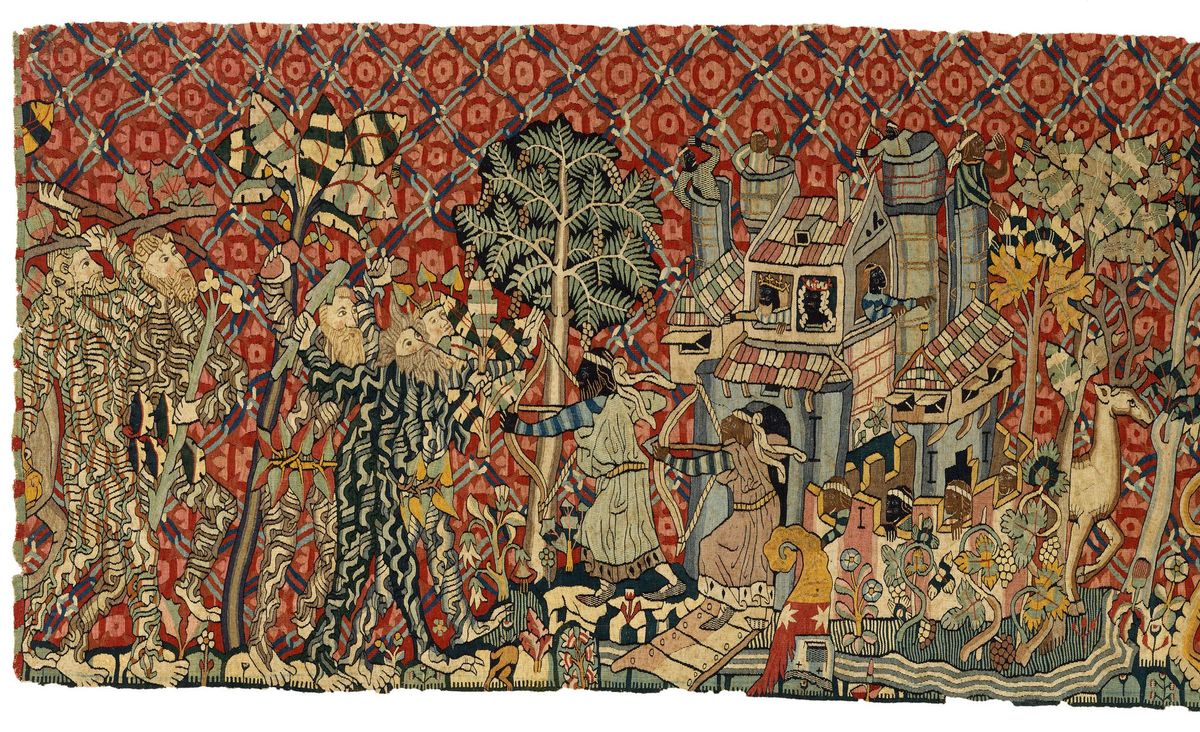

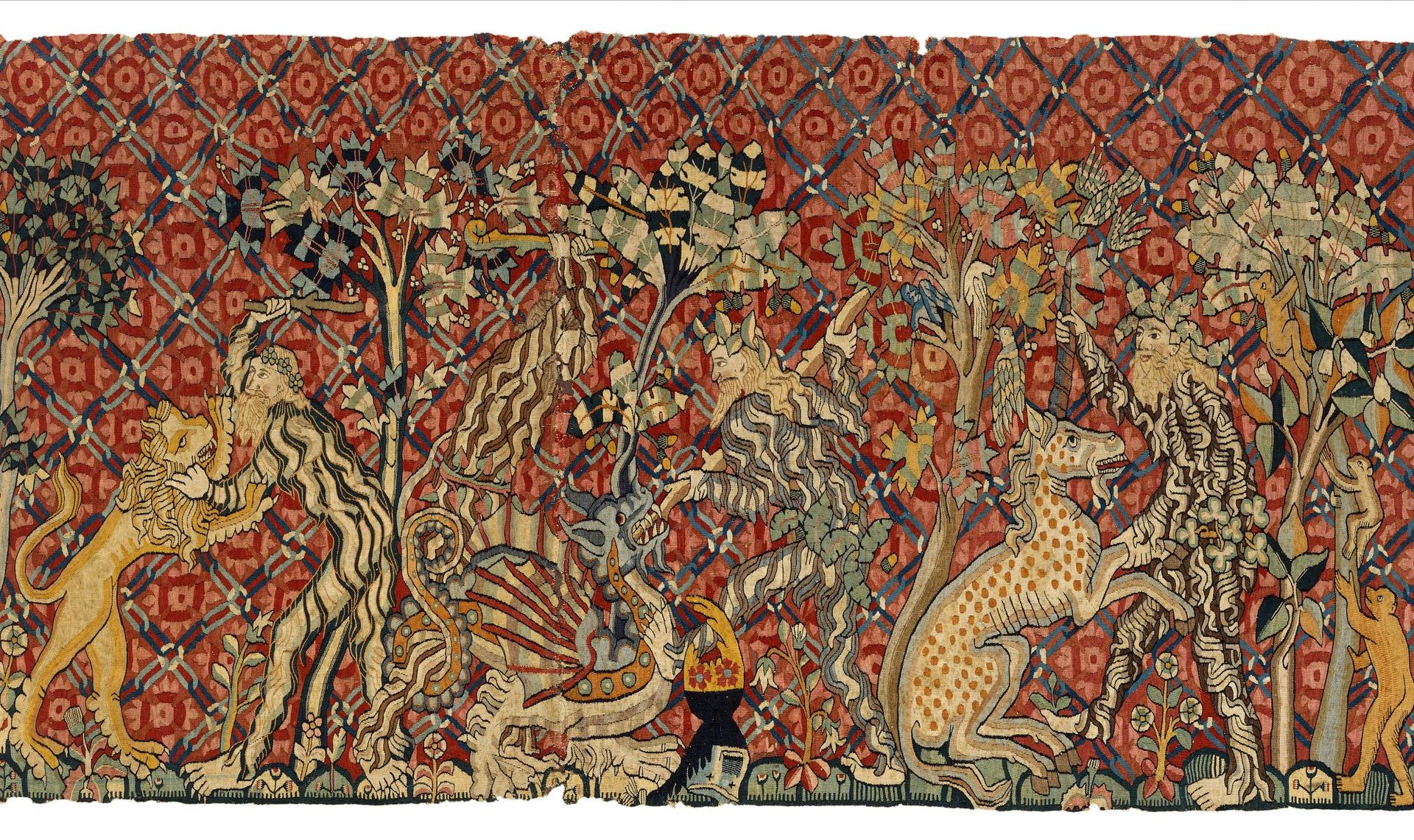

The tapestry, which measures nearly 5 metres long, was possibly made in Strasbourg (now France) around 1440. It depicts a group of “wild” men covered head to toe in long hair— and even a hirsute woman with two children—along with an army of animals including a lion, dragon, unicorn, attacking a castle defended by Moors. The tapestry with its Teutonic theme would have been a highlight of Goering’s huge art collection, although it includes an early, positive representation of African men, which might have jarred with the Nazi’s belief in Aryan supremancy.

A detail of the tapestry Wild Men and Moors, from about 1440 Charles Potter Kling Fund. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Reed says the tapesty’s survival through the Second World War is remarkable, as is a Jewish collector hiding it successfully. Her research began in 2009, when the tapestry raised a red flag because she recognised Strauss’s name in the minimal information on file about its origin. An industrialist and art collector, Strauss was forced by the Nazis to sell his magnificent collection of Medieval religious art to pay a so-called “exit tax” to flee to Switzerland, where he died in 1941.

“I feared [the tapestry] had been sold in one of the Strauss auctions,” she says, but it did not appear in any of the sale catalogues. She traced it back to a US dealer, who acquired it from Strauss’s grandson via the family attorney. “I was still curious about what happened to it,” Reed says. She found a reference to the work in a footnote of an article on Strauss’s collection that mentioned that Goering wanted the tapestry but that Strauss hid it in a Cologne bank vault.

A detail of the tapestry Wild Men and Moors, from about 1440 Charles Potter Kling Fund. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In a final twist, the curator Georg Swarzenski, who acquired the tapestry for the MFA in 1954, knew it well. He had previously borrowed it when he was the long-standing director of Frankfurt’s Städel Museum. Swarzenski, who was Jewish, was interrogated by the Gestapo for championing so-called degenerate Modern art, and was dismissed from his post at the German museum by the Nazis. Swarzenski then fled to the US, and the tapestry, which the Boston museum bought for $95,000, was one of his last major acquisitions.

Reed's use of social media reflects a sea change in some museums' attitudes to sharing provenance research about possibly problematic objects in their collections. Recently, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Nelson Atkins Museum, and most notably the Kunstmuseum Bern after it was bequeathed the Gurlitt hoard, have organised groundbreaking exhibitions of objects once plundered by the Nazis.