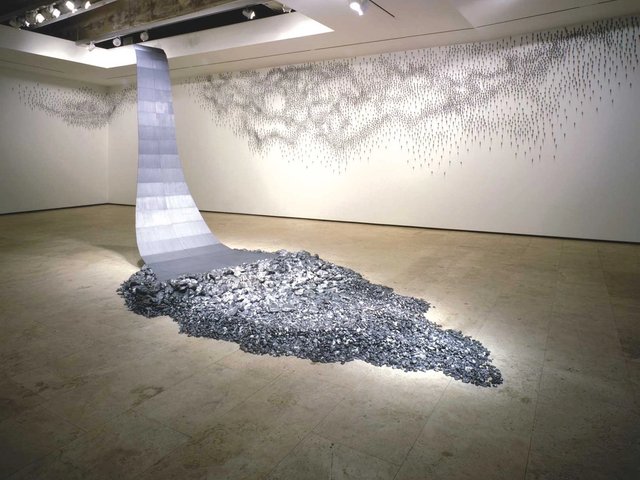

Although art historians have written about the avant-garde artists working in Brazil and Argentina in the 1940s and 1950s, less is known about the technical details of their practice—that is, until recently. Specialists from the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) and the Getty Research Institute (GRI) collaborated with the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros on a pioneering, three-year study of 30 pieces of Concrete and Neo-Concrete art by artists such as Willys de Castro, Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark and Raúl Lozza amassed by the New York and Caracas-based foundation (They are among 100 works donated to New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2016.). The results will be presented in a show opening at the Getty Center this month, which is part of its Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA programme.

The project studied how the works were constructed and the materials used, including the many types of paint and how they were applied. According to Pia Gottschaller, a GCI senior research specialist who is one of the show’s curators, “the entire gamut of 20th-century paints” was found, especially in works by artists from Brazil—a country that “industrialised quickly and sought to become an international player and not dependent on materials from abroad”. House paints were widely used because they were cheaper than artist oil paints and formulated to be self-levelling.

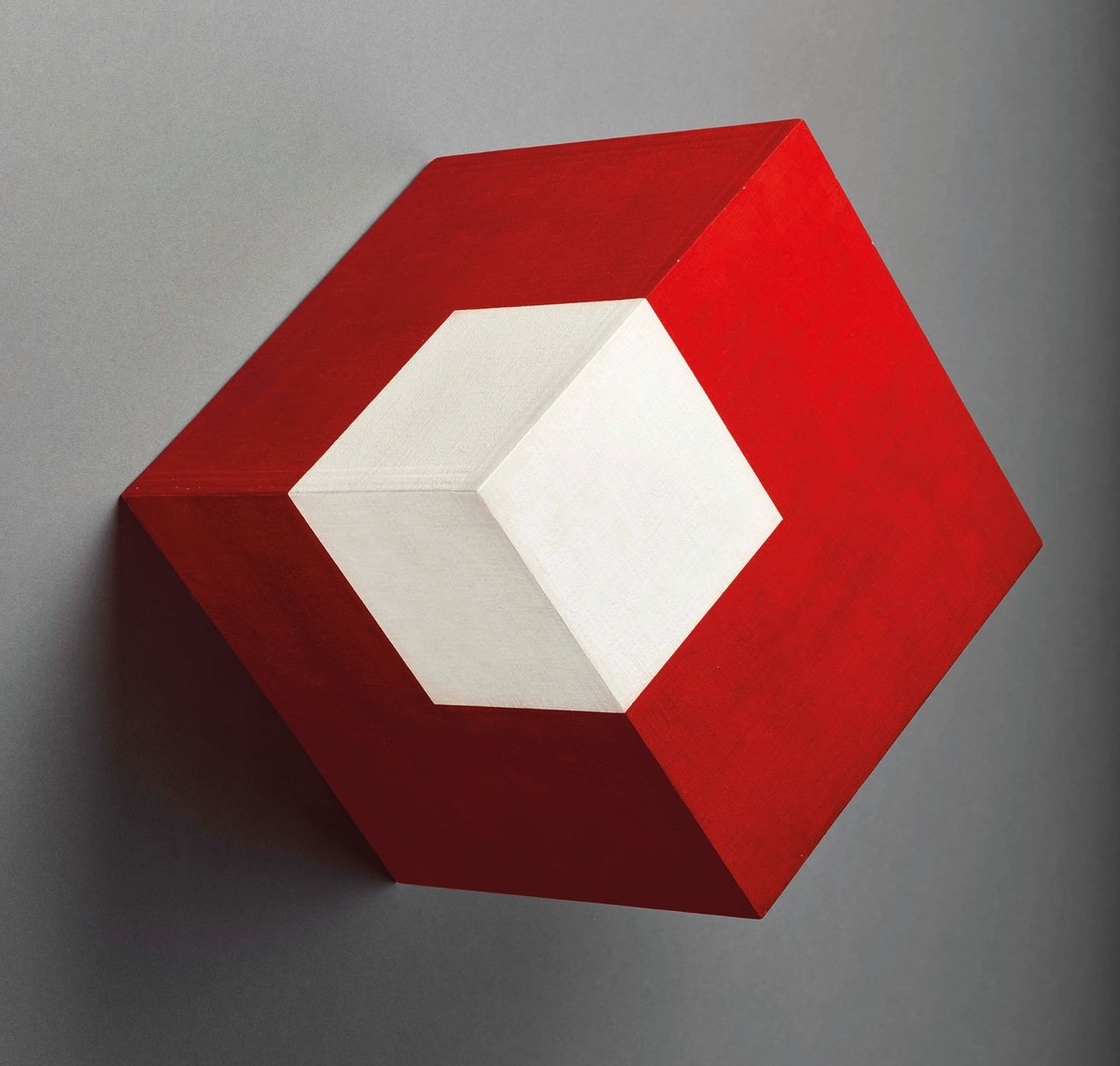

The correct orientation of Concrete works—an art form that lies somewhere between painting and sculpture—was also considered. Gottschaller found a photograph of a work by the Brazilian artist Waldemar Cordeiro, installed by the artist himself, which shows the piece rotated 90 degrees up from how it has been displayed since. The correct orientation of De Castro’s Objeto ativo (cubo vermelho/branco) (1962) was also scrutinised. “It’s not unusual for abstract artists to change a work’s orientation, and so you tend to find an arrow on the back indicating the correct direction. But in these two cases, there aren’t clear instructions,” she says.

The Getty

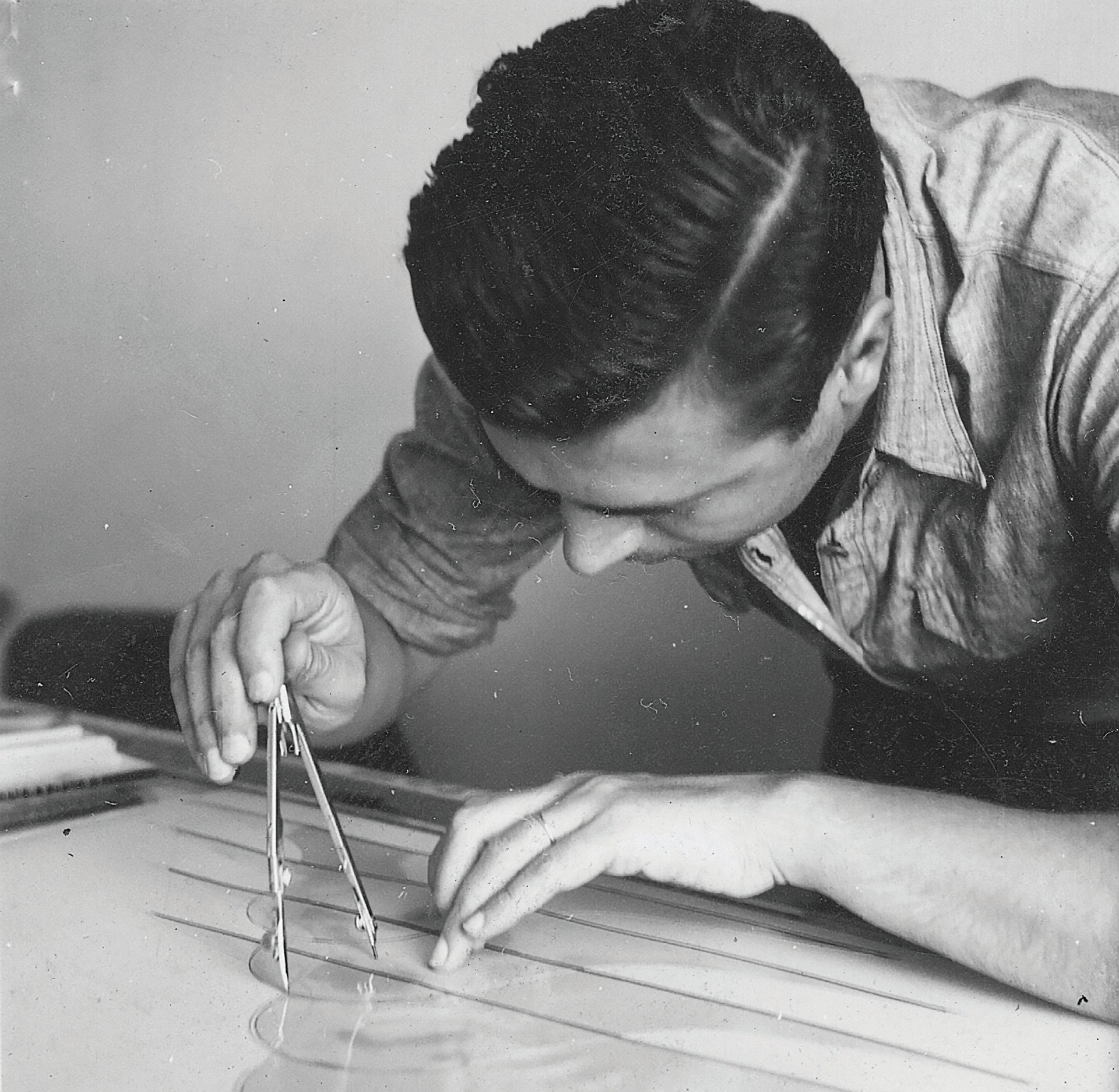

Gottschaller was particularly interested in how the artists created lines or edges. “They had strong feelings about edges and how they should look,” she says. The artist Alfredo Hlito drew them with the ruling pens used by architects, substituting oil paint thinned with turpentine for ink. The precise tool used—everything from a T-square to self-adhesive tape—can be detected by the trained eye. Gottschaller hopes to “sensitise visitors to this by sharing images of the different reliefs” in the show.

• Art Concrete: Works from Argentina and Brazil in the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, 16 September-11 February 2018