A new cybersecurity law in China, which came into effect in June, is likely to push artists into deeper levels of self-censorship. In the first week of its implementation, authorities used the law to target celebrity gossip on social media platforms WeChat and Weibo. Sixty accounts were closed down, including that of the popular film blog Dushe Dianying. Younger users of social media platforms “are feeling nervous for the first time”, says Xu Wenkai, a Shanghai- and Berlin-based media artist and blogger who goes by the name Aaajiao.

The new law requires companies to prohibit anonymity and to monitor and report on their employees’ activities online, according to the international organisation Human Rights Watch. The Cyberspace Administration of China said in a statement that the intention is to protect “national security, the public interest, as well as the rights and interests of citizens”.

The law specifically targets corporate accounts on the social media platform WeChat, which allows users to send messages and make payments, among other functions. “Everyone in China uses it every second,” Aaajiao says. “Big Brother really is watching.” His first encounter with web censorship was in 2005 when a server host he and a friend had set up at university was shut down by police. Until then, “we thought the internet was free”.

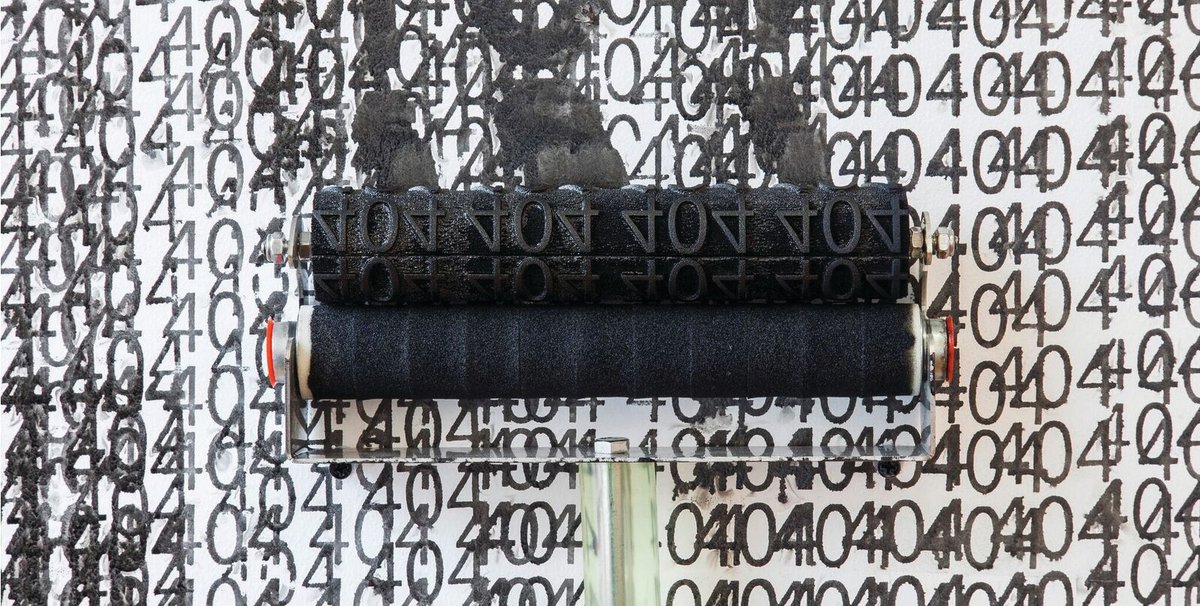

Digital restrictions are the backdrop to the work of all Chinese artists, and for some, the so-called Great Firewall—the online surveillance structure that blocks data from foreign countries—provides both subject and medium. “The Chinese internet is such a unique and rich material, I am often inspired by it,” says the New York- and Shanghai-based artist Miao Ying. “For anyone who resides in China, you will be shaped by it, not just because of the firewall. China has its own internet environment and it is developing more rapidly than anywhere else.”

Virtual private networks (VPNS), which allow users in China to bypass the firewall, are used by only 1% of the population. “You would be surprised how much people are willing to give up over little inconveniences, not big obstacles; that is precisely how censorship wins,” Miao says.

Writing in the New York Times in May, the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, who now lives in Berlin, warned that “whenever the state controls or blocks information, it not only reasserts its absolute power; it also elicits from the people whom it rules a voluntary submission to the system and an acknowledgment of its dominion”.

“Sadly, I think there will be more and more restrictions to the internet overall in the long run,” Miao says. The subject of internet censorship is also becoming more delicate in the real world. “I recently had a government official show up at a museum displaying my art and I had to censor my work that was about censorship in order to show it there,” she says. “The smarter the internet gets, the more it isolates people.”