The Chinese artist Hua Yong, who publishing videos of Beijing's controversial evictions of migrants and surrounding protests, has been released on bail following his arrest on Saturday, according to the BBC. He fled the city to avoid detention but was tracked down by authorities. He was released on Monday in time for his daughter's third birthday.

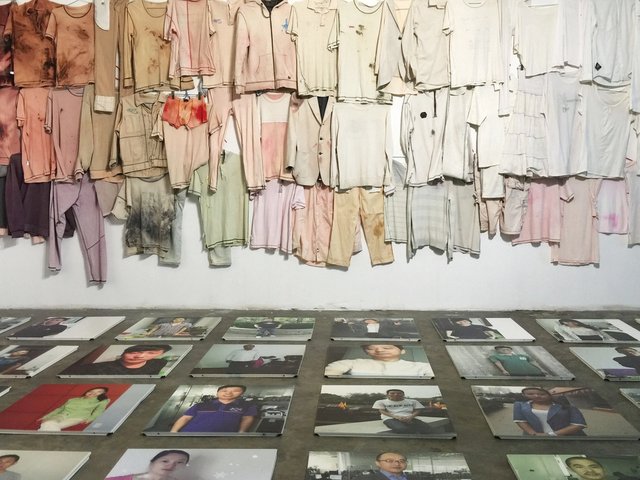

The government's crackdown on migrant workers has hit Beijing’s art community, which has lost studio and gallery storage space, as well as staff providing cleaning, shipping and fabrication. The mass eviction and demolition of buildings, which left thousands of families homeless or without power in freezing temperatures, was sparked by a tenement fire on 18 November that killed 19 people in the city’s Daxing district. In a 40-day campaign, authorities razed neighbourhoods housing the city’s millions of workers from other parts of China, labelled as “low-end population” by the government.

Beijing’s usually resolutely apolitical art establishment has been among the voices expressing outrage online (quickly expunged), and documenting and protesting about the evictions, of which Hua has been the most prominent.

Estimates of the numbers of residents evicted in December range from several thousand to hundreds of thousands, or more. The demolition of Feijiacun, a migrant village in northeast Beijing close to the 798 Art District, and home to the Red Gate Residency artists’ residency programme, prompted rare street protests that are still ongoing. Smaller protests erupted earlier in December at the demolition epicentre Xinjiancun, as documented by Hua Yang; signs at both declared, “Forced evictions violate human rights”.

Migrants from around China comprise almost half of Beijing’s population, officially 21.7 million. There are millions more undocumented migrants, but only the educated, affluent arrivals are able to obtain the jobs and flats that will secure them legal permission to reside and access social services in the city. Residency permits are impossible to get for the migrant labourers who build and maintain the city’s gleaming new towers and museums, and staff its shops and restaurants. The Beijing municipality is undergoing a massive facelift, with plans to move its government out to the eastern suburb of Tongzhou, and ambitions to cap the city’s population at 23 million by 2020 and reduce the population of its six downtown districts by 15%. Many believe the demolitions are actually designed to clear valuable land for sale to developers.

Previously, residents would have months or years to negotiate a resettlement. Before, “it was still not fair, but in the past year the government policy has been clear, to implement its vision at full speed”, says Alessandro Rolandi, an Italian Beijing-based artist, who since 2011 has run the Social Sensibility R&D Department, a programme that arranges collaborations between artists and factory workers in the Beijing factory Bernard Controls.

Demolitions earlier last year hit Beijing’s art scene more directly: Heiqiao, or Black Bridge, a farming village near the 798 Art District containing a studio hub, was demolished last spring, displacing thousands of local artists. In March, several studios were demolished in Songzhuang, the largest artist colony in China, and more than a hundred artists there clashed with police. Iowa, an artists’ community in Caochangdi, was demolished in August.

A Beijing gallery director who had storage space at Heiqiao, and did not wish to be identified, says that the village was home to about 80,000 migrants, and estimates that the number of people displaced in demolitions, including the latest crackdown, is in the millions. “Artists are suffering the ‘collateral damage’ in the whole thing, as obviously the target is not the very small population of artists,” she says. “The reason artists are suffering is that most of the studios are geographically next to the ‘slums’ where the migrant workers have been living. Sure, there are artists, mostly young, who lived in the studio besides working there, but most use it more as workplace, not like the migrant workers, who were crammed in a space sharing public facilities. Studio villages are not only a place you work (and sometimes live), but also [offer the] possibility of sharing resources: shippers, logistics, gallery and museum visitors.”

During Beijing’s mid-2000s art heyday, the city was a beacon of opportunity for young artists around China. Now the country’s young artists are flocking abroad or to more welcoming southern Chinese cities. “Beijing was a place where people met in a special way, with small villages to gather in informally,” Rolandi says. “That has started going away. They’re taking away that lively energy that makes a place beautiful.”