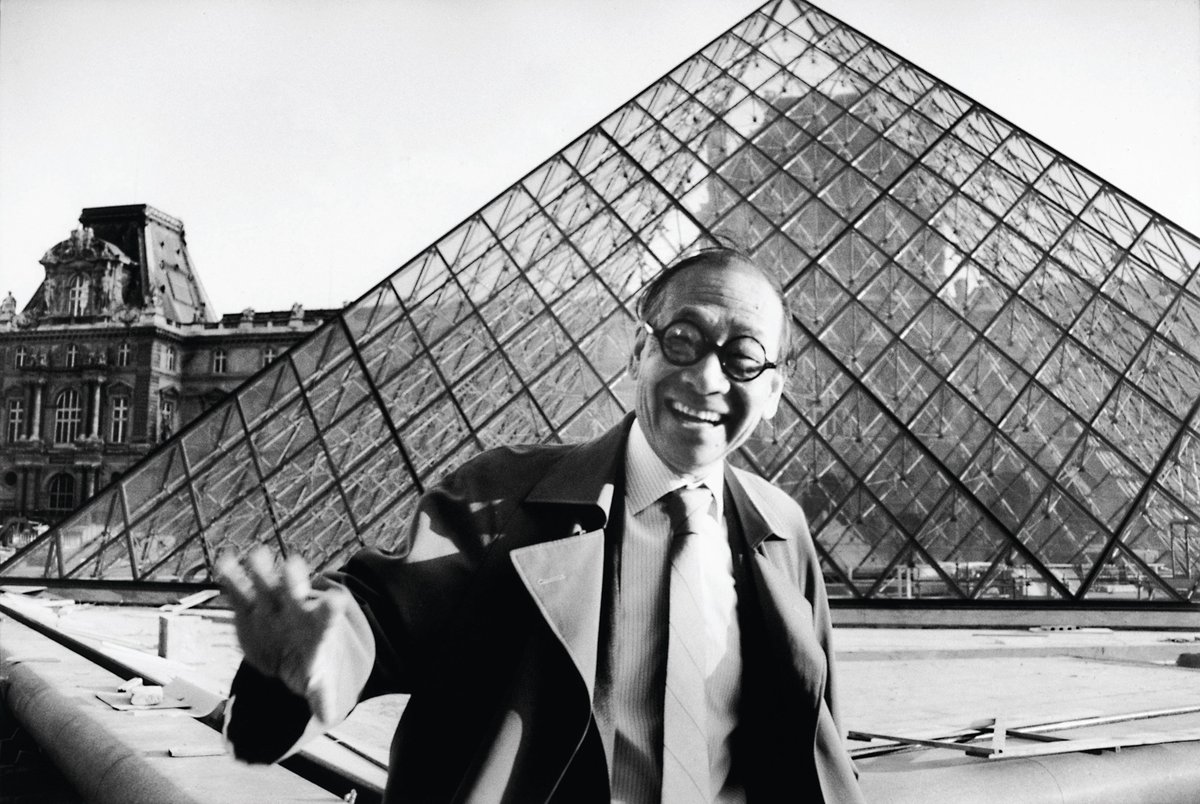

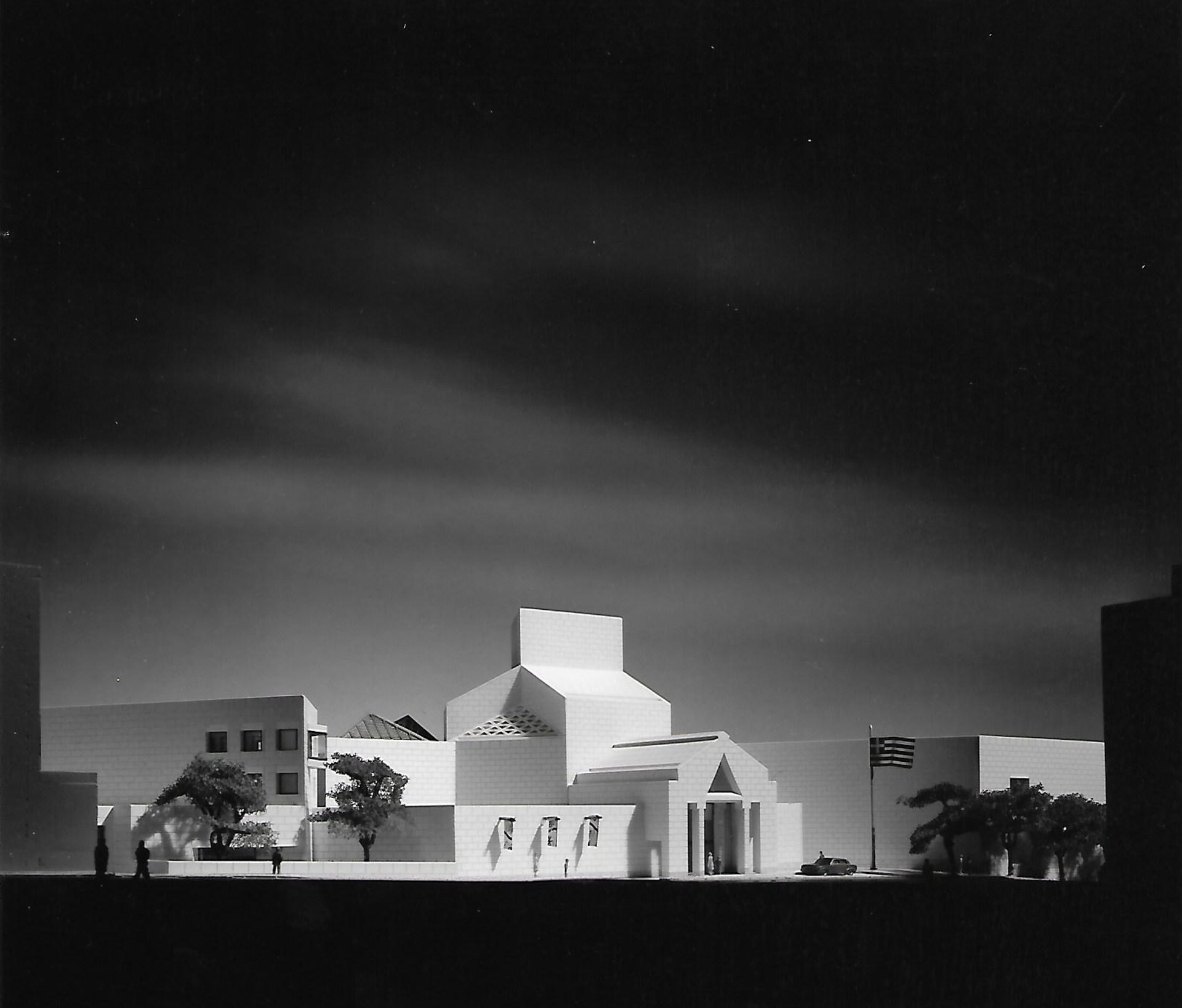

The history of architecture is nearly as much about buildings that never got built as ones that did, so on the occasion of the opening of the Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Modern Art in Athens this October, The Art Newspaper is republishing its 1994 interview with the late I.M. Pei about the uncharacteristically romantic museum, based on a Greek orthodox church, that this usually minimalist architect designed for the very fine Goulandris collection of Impressionist and early 20th-century art.

Unfortunately, this design was to remain “paper architecture” due to archaeological, political and bureaucratic obstacles that dragged on for years, and the museum has finally been housed in a well adapted existing building, but it is worth remembering the elegant, allusive creation that the Goulandris had the taste to commission and that might have been its home.

It was to have been built in a pale limestone, with a footprint of 17,500 sq. m, in the centre of Athens, close to the Benaki Museum and the Cycladic Museum (built by another branch of the Goulandris family) on a site donated by the Greek government. The foundation, based in Lausanne but deriving its wealth from the Greek family's shipping interests, committed $14 million in 1993 to its erection and then, as now, was to cover all running costs.

Early in 1994, The Art Newspaper met with I.M Pei in his Madison Avenue office and asked him about the Athens project and his work on museums in general.

The Art Newspaper: Is this your first project for the Goulandrises, and your first in Greece?

Ieoh Ming Pei: Yes, this is the first.

What is your relationship with the Goulandris and their foundation?

I have known them for 27 years, just as friends.

Could you describe the site?

It's a park bordered by the Byzantine Museum; they are in the process of expanding. Next door is a neo-classical officer's club. Across the street is a row of modern, multi-use residential and office buildings, and a music school. None of the neighbouring buildings is what I call a monument.

When did you first visit Greece?

In 1951 as a student tourist. I have returned quite frequently, though, because I have so many friends there.

Elise Goulandris with I. M. Pei (centre) Courtesy of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners

Has the location influenced your design?

Not very much. Athens as a city is not too distinguished architecturally, nor does it have any limitations that one has to design for, or design against. If there is a strong architectural personality in Athens, I would say it is neo-classical.

Has the legacy of classical antiquity influenced your design?

More than the neo-classical. The high point in Greek architecture was probably the 5th century BC and that is still very instructive today. I don't mean in the literal sense—I'm not using a Doric column or a pediment—but in its simplicity, and the role that architecture played in daily life. I would like to see this building play a similar role, where people will come and meet friends and discuss and stay. That is why we have a garden with a fountain surrounded by orange trees, a restaurant, and an indoor garden for winter. A row of cypresses defines the site on the side of the Byzantine Museum and leads in from a public square. What I most admire of the Athenian architecture of the 5th century BC is that it was a background to life.

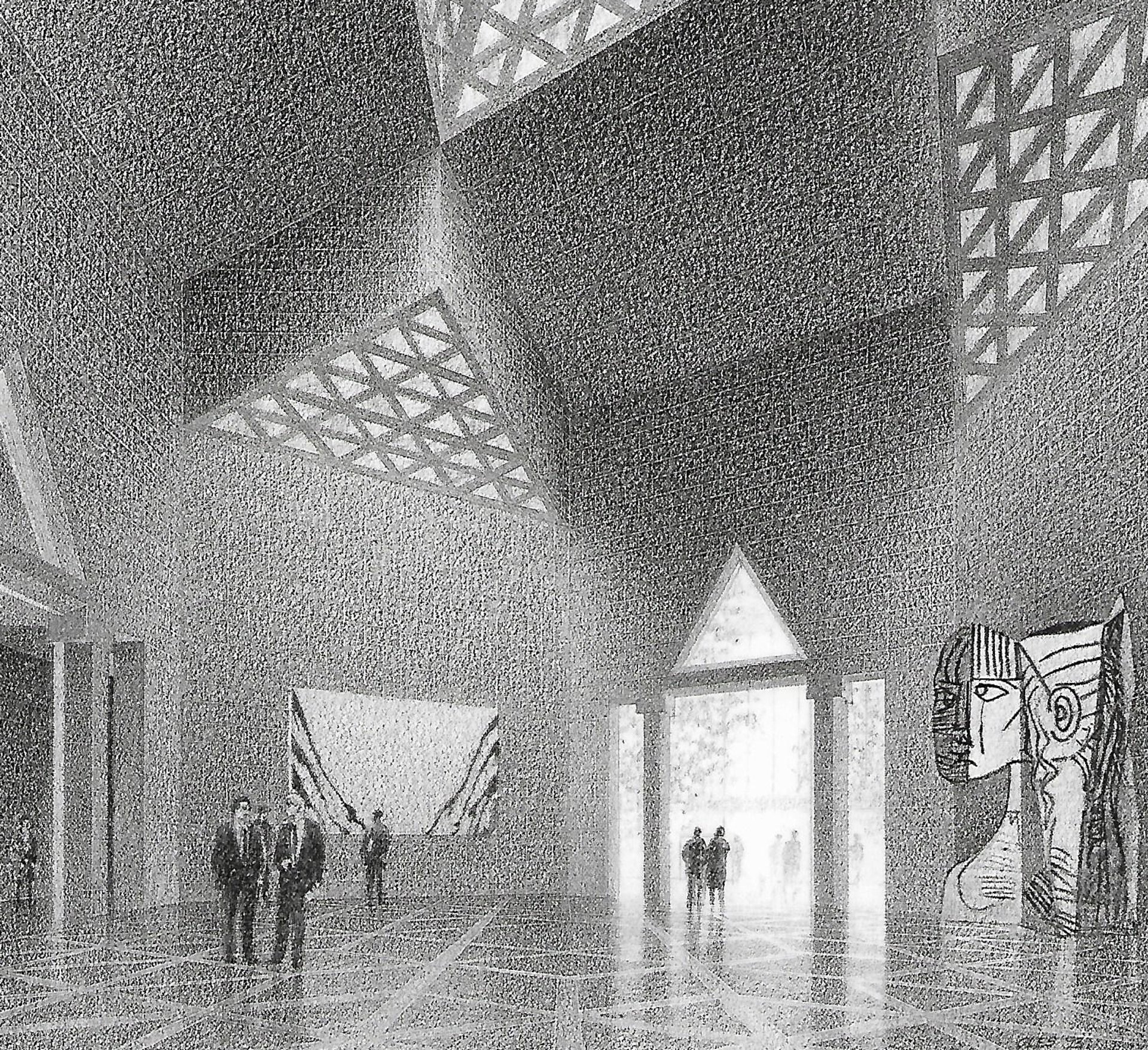

The museum has two floors below ground and two above, except the administration wing which is four stories. In the centre is a hexagonal reception hall more than twenty-five metres high in which I have tried to create the ambience of a Greek church. The harsh light of Greece is softened as it filters through the grillwork of thinly cut alabaster set in the skylights and gables.

Because of the harsh Greek light, I want the building material to be light-coloured rather than dark. Yet I don't want white like the structures on the islands of Greece; because of the pollution of Athens; a white building would be stained very easily. I will use a pale material, preferably a limestone, because marble cannot stand the wear and tear caused by the acid in the air. We are trying to find in Greece or nearby a stone similar to the French limestone used in the Louvre, but it doesn't really save that much money, so we may import it.

Have you had any special instructions concerning structural features or amenities?

Yes. This museum has to be many things besides a place to exhibit art. A small museum such as this plays a different role in Athens than it would in New York, where we have many specialised museums. Here it has to serve a wider public. It has to provide a place for important public occasions, and because of that we have an auditorium and restaurant facilities. There is the administration wing for the foundation's offices, a conservation studio and a library. And there is a certain emphasis on children, such as an art laboratory in which they can experiment with art.

An impression of the interior of IM Pei's never-built Goulandris museum in Athens Courtesy of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners

As far as the programme for displaying the work of art is concerned, did the foundation leave that to you?

No. They have some specific ideas about that, and we have to incorporate them. For example, they own an important painting by El Greco, “St Veronica’s Veil”. Because there are only a few examples of El Greco in Greece, it is featured in a room alongside certain Greek icons to relate the two.

About half the museum is devoted to galleries. How did the character of the art affect your design of those spaces?

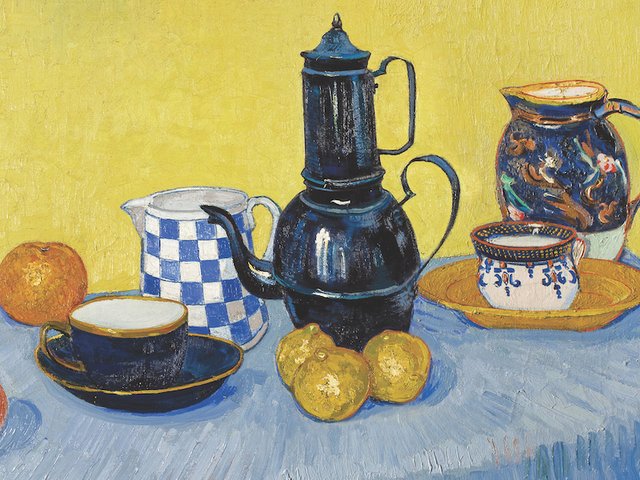

For the Impressionist collection, for instance, which is one of the finest anywhere, I would like to bring daylight in. Impressionist paintings look best when there is daylight, so they are in sky-lit galleries on the second floor. I first saw the collection many years ago in Paris and I am familiar with the paintings by Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Derain. The Greek collection—that I don't know.

Are there other museums of late 19th-century European art in Athens?

No. The wonderful National Museum is mostly for antiquity, and so is the Benaki Museum. The Cycladic Museum is probably the best private museum of its kind in the world. Then there is the Byzantine Museum. But for European nineteenth-century art, this will probably be unique in Athens, although there are many works in the homes of private collectors.

Will there be changing shows?

Yes. I believe the foundation's works will be permanent, but there is a space we have designed for temporary loan exhibitions. You need that in order to keep the museum alive.

Is the museum intended to accommodate many people, or is it to be more intimate?

It is incredibly flexible: if they get 200,000 visitors a year, that's fine, and if they get ten times that, it will be alright too.

A model of Pei's Goulandris museum, based on a Greek orthodox church Courtesy of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners

Is it in some sense true that museums are the secular cathedrals of the 20th century?

I think museums represent the aspirations of the people in a particular society; certainly not as much as religion, but they have reached a point where they have become very, very important.

Do museum structures have a symbolic language as did cathedrals?

To my mind, no.

Do certain museums stand out, in your opinion, as truly exceptional?

If you ask me which museum has the best collection of Renaissance art, I would say the Louvre and the National Gallery in London. But if you ask which is the best museum architecturally, I have difficulty answering. Some museums can be seen in a glance—Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim, for example. You walk in and there it is. But I cannot compare the architecture of the Guggenheim with the architecture of, say, the Metropolitan Museum. One was built... just like that. Whereas the other is an accretion, like the Louvre, the National Gallery in London, the British Museum. Great museums usually have a long history behind them.

Carl Friedrich Schinkel, John Soane, Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Kahn are regarded as having designed great museums. Has any of them influenced your museum work?

Wright has to be the greatest architect of our time. No question about that. But he is not the only one. If you want the names of architects that have influenced me, I would say not Schinkel— Schinkel is of another time—I would say Le Corbusier has to be it. Then you have Frank Lloyd Wright, and Louis Kahn to a lesser extent.

Is there a common thread through your museums?

I'd like to think so. I cannot describe it, but there has to be—it comes out of my head—yet each is different. The Athens museum has almost nothing in common with the Louvre, for example—maybe technical details like the use of materials or the way I bring light into the room—but otherwise they are different.

You are well known for the monumental ideas that govern your projects, such as the pyramid at the Louvre, of the double-triangle floor plan of the East Building of the National Gallery, Washington. Is that where you begin, with a design concept?

Always. Concept is fundamental. If you do not begin with a proper concept, it doesn't matter how well you execute the project, it will not be successful. The conceptual phase is most important, and I probably put the greatest amount of time and emphasis on it.

So you work mainly on the design phase?

The conceptual work is what interests me, but I make sure that it's executed in a way I like. The details are important as well.

Can you explain the symbolism of the triangle and pyramid and retrace their genesis in your work?

Geometry is fundamental to architecture. All the great buildings in history are based on geometry. A triangle happened to be a geometric shape, that's all. I am not exclusively interested in triangles. Sometimes I use circles, arcs. But a triangle is unusually stable. it is a rigid form and cannot twist and turn. A square can be compressed, and it becomes an oblong. But you cannot change a triangle. Geometry is basic, and it is not limiting; it has endless possibilities.

Some of your buildings resemble minimalist sculpture. Are you aware of any affinities between your work and contemporary art movements? Have any visual artists influenced your work?

Art and architecture are not the same discipline, but they are very much related. Therefore, if you compare my work with work of the plastic arts, I would say that you may be able to find some things in common. I tend to want to find the simplest way to express an idea. If you say this is akin to Minimalist art, so be it. But I really don't think one can compare it that way. Some may find my buildings look simple but then to reach that simplicity, it's a long, long process. I am for simplicity, but simplicity doesn't mean simple-mindedness.

Does the concept hinge mainly on the building’s intended function?

More than function. Architecture is a social art, very much tied up with society. It is not only a matter of how the building will be used. But also, what role that building plays in society

To what extent do the site and surrounding structures affect the concept?

The context—where it's situated—is of great importance. One never builds in isolation, particularly in the city. The environment is very, very important.

Do you conceive of the design mainly in terms of space, visual composition, or symbolism?

Everything. It depends on the assignment and the role the building will play in a particular context. All buildings are different. A monument, for example, is mostly symbolism, and symbolism is mostly form, not space—like an obelisk; there's no space inside it. But when the building is designed for use, which is 99.9% of buildings, then space is important. The function of the building has to be understood, then relative importance will be applied to different aspects.

Which aspect tends to predominate when designing an art museum?

An art museum is symbolic, but at the same time it has to function, to provide the best possible conditions for viewing art. What is an art museum for? To display art. To display art for whom? For the public. Therefore, the building must make it possible for the public to enjoy coming to see works of art. The enjoyment is not only how the painting is lit—that's important—but also the ambience, the space: is it too cramped? Too big? Or is it just right?

Do you consider what kind of art is going to be shown?

Very definitely. The objects that will inhabit a museum have a great impact on what the design is going to be like. A decorative arts museum is very different from a museum of Impressionist paintings. It's almost an entirely different programme. Take the Louvre: that's an encyclopaedic museum, a museum that has everything in it; that is very different from a museum such as the one I am doing in Athens.

Do you believe that works of art should be presented in simulacra of their original contexts, or that they can be transplanted and retain their aesthetic integrity?

They have to be transplanted. How can it be any other way? A painting comes out of a palace. You can't design a palace!

Do you regard yourself as a modernist?

What else can I say? Architecture and life are so closely related. My work is to express the time in which I live and work. And if that's the definition of being modern, yes, I am a modernist.

Do you include works of art within your designs?

When I can, I do.

Were the Calder stabile at MIT and the Calder mobile in the National Gallery of Washington parts of the original plans for those projects?

Yes. It is very appropriate, particularly for an art museum, to inhabit a space with works of art of a particular scale. If you put a tiny little sculpture in a big space it would be lost. I choose certain art not only because I like the work of that artist, but also because I want to make sure that the scale of the object is appropriate for the space in which I want to put it. Carter Brown, then director of the National Gallery, and I knew that a Calder mobile would be ideal in the atrium of the East Building and we determined its size. Calder himself said, “You know the space better than I do”, but obviously we had to get his approval.

Henry Moore and I talked for a long time before we arrived at the right size for his sculpture near the arch I built in front of the library in Columbus, Indiana. Ideally the artist and the architect should work together on a piece that is put permanently within a work of architecture. Then it is no longer collecting but making that work of art play a role in a space which is architecture itself.

You recently retired from the firm you founded. What is your role in the company now?

I continue to finish those three or four projects that I had begun when I retired in 1990. But at the same time, I felt that after my retirement I could enter into another phase of my practice. I'm taking on small projects that interest me, which I couldn't when I was part of the firm,. when I had to keep a very large organisation active. Small projects like the Athens museum.

• This article was first published in February 1994 under the headline: The Goulandris Foundation: A major private museum of Impressionism and Greek art for Athens