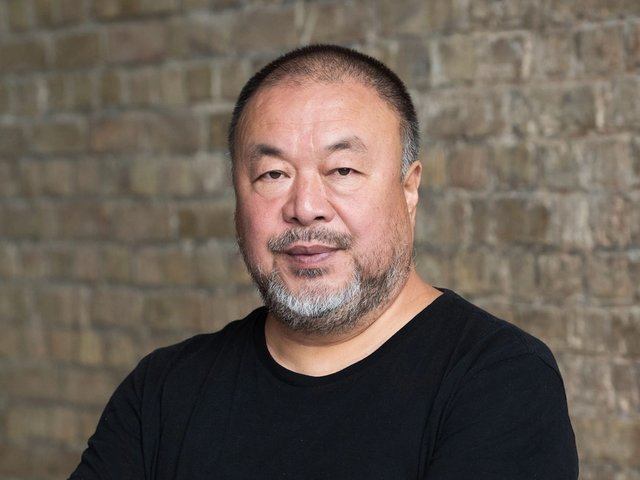

Since his exile from China began in 2015, Ai Weiwei has focused his attention almost exclusively on the refugee crisis, with scores of international shows and his critically acclaimed documentary on the subject, Human Flow (2017). A selection of his migration works has landed on the shores of Hong Kong for the show Refutation (until 30 April) at Tang Contemporary Art’s new gallery space in the H Queen’s development. Here, Ai tells us about his old love for Hong Kong, his new love for Latin America, and why critics of his work should seek medical advice.

Ai Weiwei left China for Germany in 2015 2018 Shutterstock

The Art Newspaper: The theme of your exhibition at Tang Contemporary Art is refugees. How will these works resonate in Hong Kong in particular?

Ai Weiwei: Hong Kong received a lot of refugees from China [in the 1940s and 50s]— people would just swim [across]. But now there is still pressure, with refugees coming from neighbouring countries like Myanmar. It’s quite difficult for them to stay in Hong Kong because it is owned by China now and is becoming much less independent.

Have you seen Tang Contemporary Art’s new space?

I haven’t seen the space [but] I admire the owner for his courage. I had my first and last show in mainland China in 2015 [at the Beijing branch of Tang Contemporary Art] and at the time my status was very fragile, just before I got my passport [back from the Chinese government]. It was a very big show and there were a lot of secret police. And [now], doing a refugee-oriented show in Hong Kong, the gallery owner must know that it’s not going to be a commercial type of show. But still there are individuals trying to make an effort. I think it will make some difference to the Hong Kong art scene.

Will you be coming to Hong Kong?

It’s not possible; I will deliver the work—it’s better than me.

In the past year many international galleries have opened in Hong Kong, including Hauser and Wirth, Pace and David Zwirner. Do you think this is going to change Hong Kong’s art market?

With its location and its political position, Hong Kong should be the most lively spot. I think it’s in a better position than Tokyo or South Korea. But still, it’s not booming—I don’t know why. But I think it has the potential.

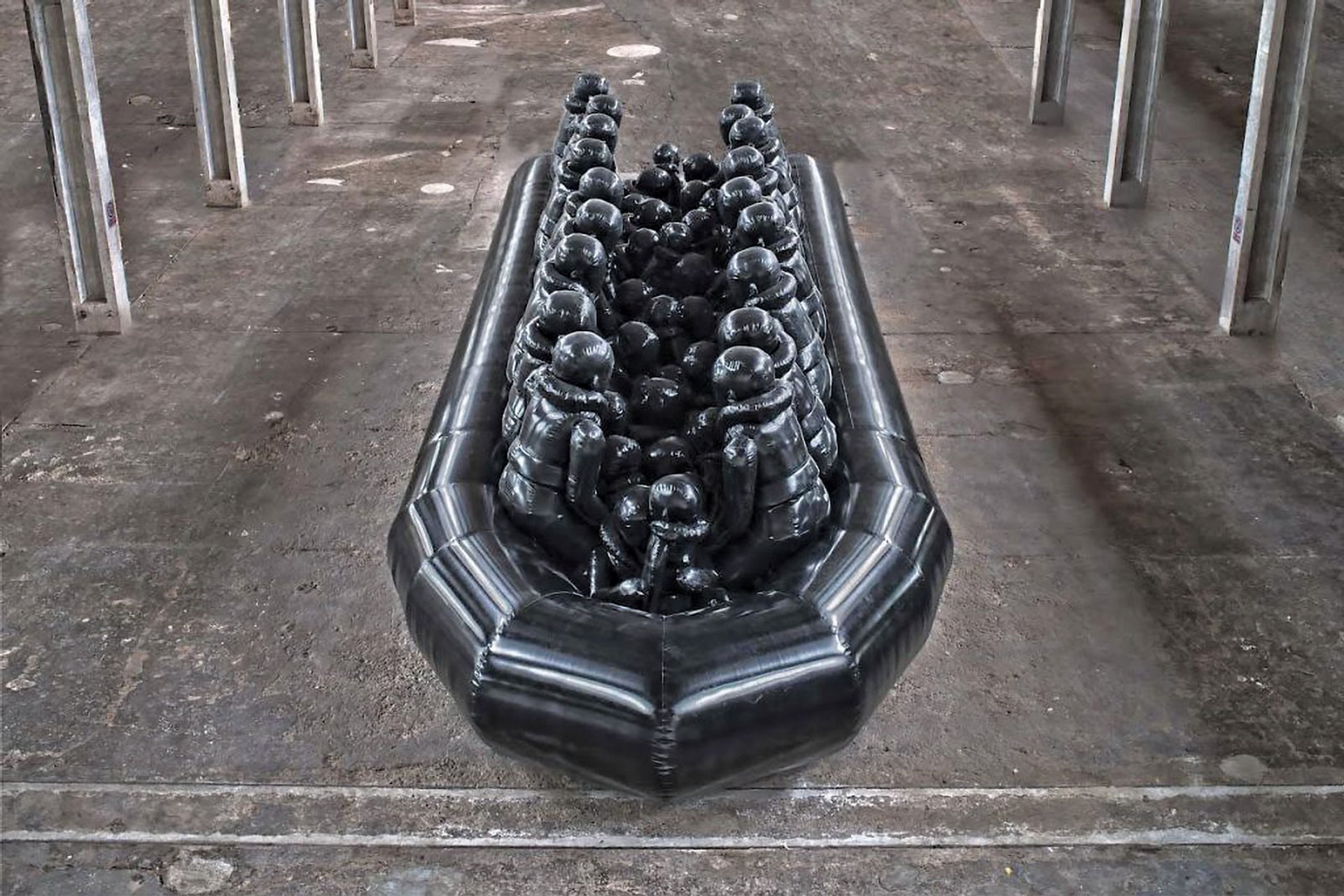

Ai Weiwei’s cast of a dinghy of refugees, Law of the Journey (Prototype A) (2017) in his show at Tang Contemporary Art Courtesy of Tang Contemporary

How is Hong Kong significant for you personally?

I have a very special place [for it]. For such a little island, when I was detained [in China in 2011], it had the strongest voice [against the government]. It was not only the art community but also ordinary people, which is very impressive.

Your half-brother, Ai Xuan, also has a show on in Hong Kong. What do you think of his work?

Oh wow, I didn’t know. Then you will see two extreme ends of something called art. We are blood related but, besides that, we are completely unrelated.

You’ve said before that you can’t imagine living in China again as it’s unsafe. Will you stay in Germany?

I’m very fortunate—I’m like a high-end refugee. I can speak to the media and I get to do so many shows but I have a nation I cannot go back to. It’s very hard to think conceptually “I am settled here” because everything is so uncertain. Uncertainty gives me a clear understanding about the refugee condition.

Do you feel that your humanitarian focus and symbolic position as a critic of Chinese state oppression have clouded your activities as an artist and affected the reception of your work on its own terms?

I don’t think so, I think it just helps it. [Without it] I would have much less understanding of humanity and personal freedom—then what would my art take from? I think every artist has to make an effort to not play safe but to follow [their] first thought, [their] instinct. Maybe you can contribute to so-called art or art history or maybe you’re a failure.

You’ve been criticised in the past for some of your performances relating to the refugee crisis, such as your restaging of the photograph of the drowned Syrian boy Aylan Kurdi and handing out metallic emergency blankets at a gala. What do you make of such criticism?

I think if they feel something is bad taste, they first need to [look at] their sense of what taste is. They can either go to see a doctor or a dentist. As artists, we are not decorating their aesthetic views, we are always working in a dangerous area and questioning existing judgements, [whether] moral, philosophical or aesthetic. You can’t always have so-called good-taste art. I don’t understand why that sort of comfort is important. Art has to be relevant. Relevant means making the people whose life and moral judgements are so fake at least feel uncomfortable about it. If I cannot make them feel uncomfortable, I am a total failure and I will feel sad about why I am still doing this.

So in that sense, the criticism is almost good for you?

There is almost no real criticism now. They just tell you they either feel bad or sad but there is no criticism. Why do you feel bad? Why can artists not pose in a certain position, whether as Jesus or Aylan Kurdi or whoever? What is so wrong about it? It’s a form. Are there certain forms that are forbidden or that you just can’t talk about? I don’t understand it.

Your Instagram feed is full of snapshots from your life. I noticed you’ve been on a lot of trips to South America and there are also pictures of you making a body cast.

This year and next year I have big museum shows in Argentina, Chile, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Mexico. I am fascinated by the Latin American nations. We are doing a lot there preparing for those shows—we have 25 of our studio members in Brazil right now. I got back five days ago and in a few weeks, I’ll be there again. The body cast is for a new work we are developing in Brazil—we are doing a lot of new exciting works.