The sale of vinyl records in the UK has risen remarkably over the past decade, from a low of 205,000 copies in 2007 to 4.2 million last year, according to the Official Charts Company. Gennaro Castaldo, a spokesman for the British Phonographic Industry (BPI), puts this down to events such as Record Store Day, a new audience among younger, engaged fans, as well as cover art and sleeve notes, “which contribute to the appeal of vinyl as collectible artefact”.

There is, of course, a long tradition of artist-designed album covers—perhaps most famously, Andy Warhol’s groundbreaking designs for records by the Velvet Underground and the Rolling Stones. But artists are increasingly responsible for the content on the records as well as the packaging. At the forefront of this is the Vinyl Factory—a vinyl pressing company, record label, publisher and, more recently, collaborator on major exhibitions at the Store X space in London. Although the company was founded in the early 2000s, the record label began in 2008 and “the vision was always to work closely with musicians and artists, to give them the tools to be as creative and close to the process as possible,” says the Vinyl Factory’s project manager Vickie Amiralis. “The first fine artists we worked with were those who had bands, or for whom music and sound was an integral part of their work, such as Martin Creed, Jeremy Deller and Christian Marclay.”

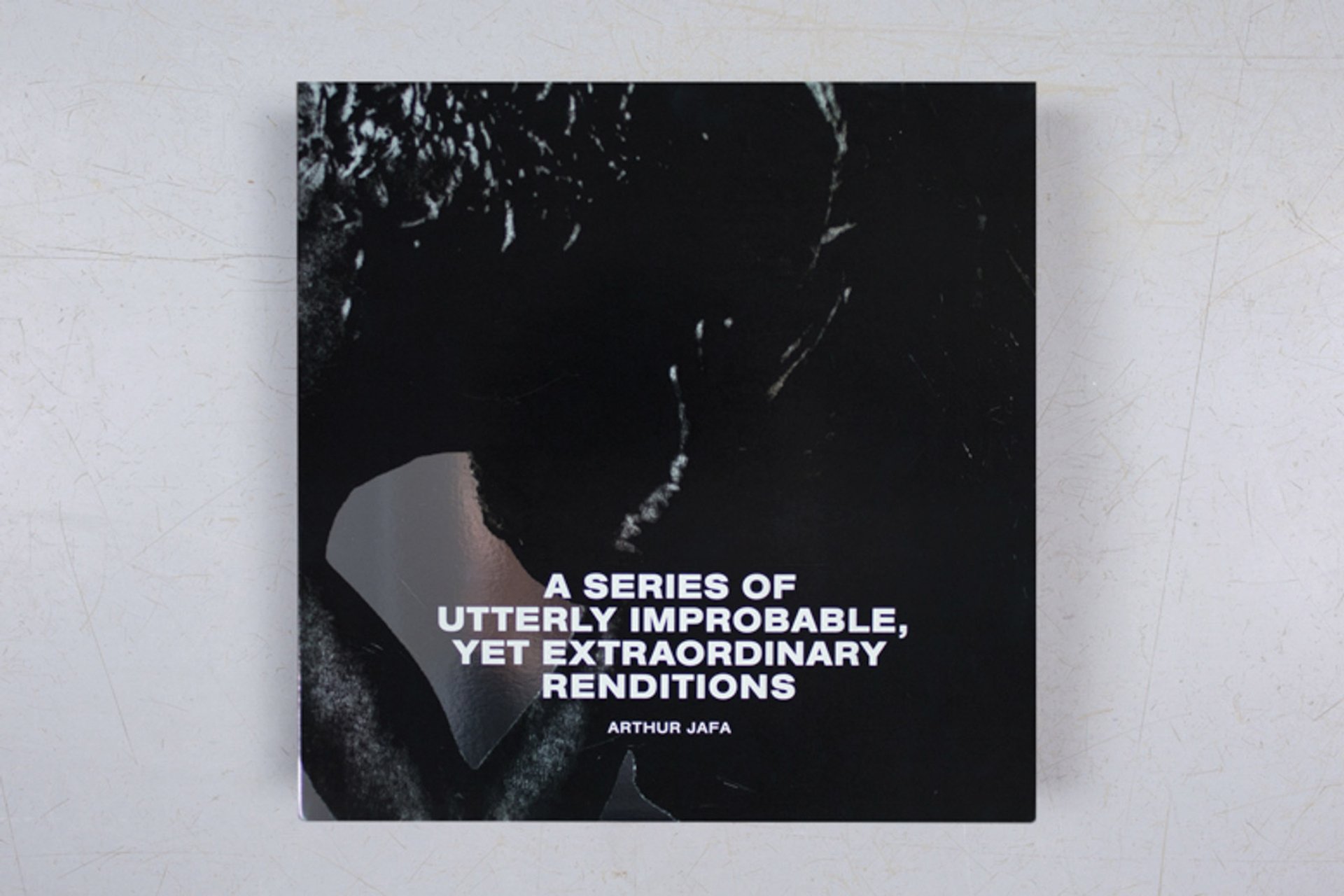

Arthur Jaffa, A Series of Utterly Improbable Yet Extraordinary Renditions © The Vinyl Factory

The Vinyl Factory owns and runs the biggest pressing plant in the UK. Curious artists have visited the plant, Amiralis says. “Christian Marclay was perhaps the most enthusiastic—he spent a few days there, experimenting with lacquers, cutting them up and collaging them back together.” This collaboration with Marclay led to the creation of the Vinyl Factory Press, a mobile vinyl factory housed in a shipping container, used during Marclay’s White Cube show in 2015. It was used to record and press 15 records, each in an edition of 500, featuring collaborations with musicians such as Mica Levi and Thurston Moore.

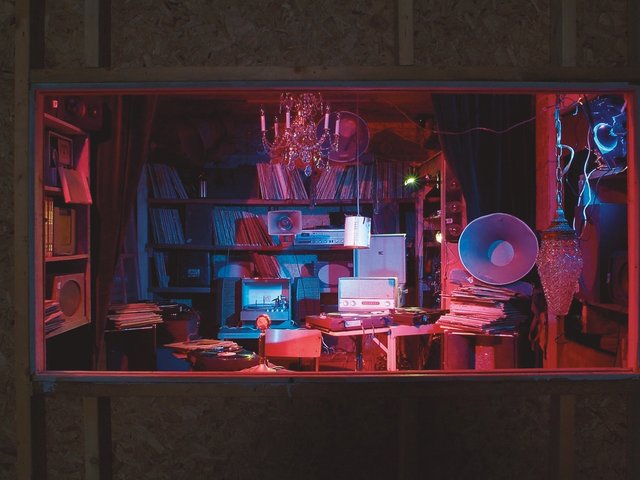

The Vinyl Factory’s direct-to-disc mobile unit, the VF Lathe, made its debut at the 2015 Venice Biennale, recording works by Jeremy Deller and Isaac Julien, among others. In 2017 Arthur Jafa used it creatively during his Serpentine Sackler Gallery show, to record jazz musicians in different London locations. As Amiralis recalls, their respective parts, played to a guide track without hearing one another, were streamed live, “so you only heard the whole composition if you were in the gallery”.

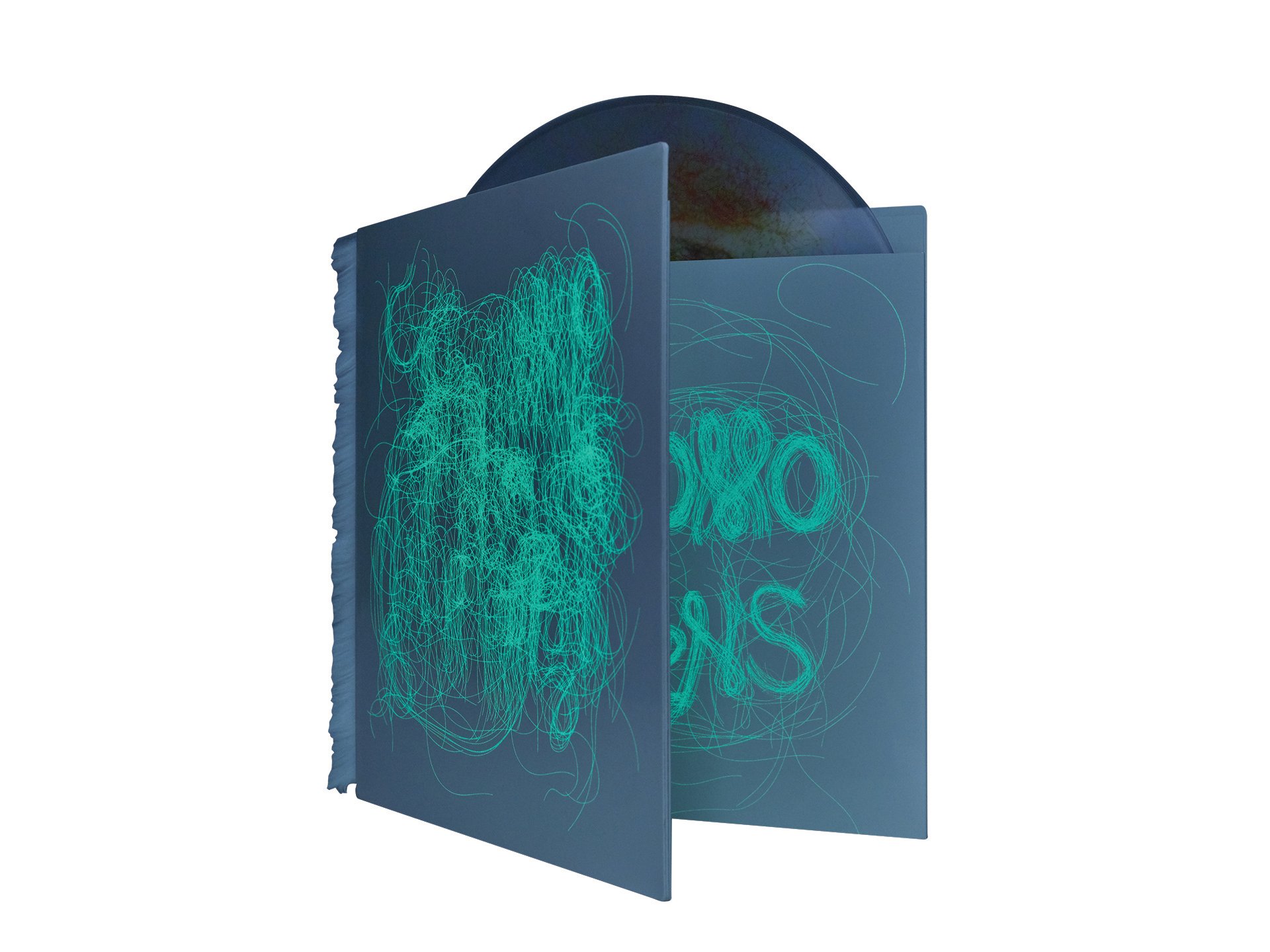

Hrafnhildur Arnardóttir, aka Shoplifter’s Chromo Sapiens LP Courtesy of karlssonwilker inc

With the advent of more convenient means of recording and disseminating sound, what is it that makes artists increasingly want to use this seemingly outdated medium? “Because it’s physical,” says the US artist Taryn Simon, who in September released a double album of songs of grief and mourning from her powerful performance, An Occupation of Loss (2016). “The laments have been etched into something circular and cyclical that requires intention and interaction from the listener,” she says.

Similarly, the UK artist Jeremy Deller says the appeal of vinyl is that “it’s a nice object, a good shape”. Deller has created several records with the Vinyl Factory, including last year’s Freetail Dub, a dub mix of bat recordings replete with a glow-in-the-dark cover. However, Deller sees these records as “just a decent piece of documentation” rather than works of art.

Aziz Tamoyan and Kalash Tossouni Boudoyan Taryn Simon, An Occupation of Loss, London, 2018 Photograph by Hugo Glendinning. Courtesy Artangel

At the Venice Biennale, this year’s Golden Lion-winning Lithuania pavilion has a vinyl catalogue for its operatic work, Sun & Sea, by Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė and Lina Lapelytė. “Vinyl catalogues can hold an enormous amount of text materials, while at the same time maintaining a relationship to the idea of an object one can cherish [and] collect,” say the artists behind the work. It also provides “a glimpse of what the work is—it’s a very important fracture of the piece—but it’s not a complete work”.

For Hrafnhildur Arnardóttir, aka Shoplifter—who created the Chromo Sapiens LP to accompany her Venice Biennale installation for the Icelandic pavilion—the record has several functions: it is “a special edition artist multiple and an extension of the installation, supporting the show, but an independent art object as well”. The allure is also the physicality of vinyl. “It’s more tactile and you have to handle the object in order to play it,” she says.

BPI’s Castaldo points out that some vinyl fans say “that the less compressed audio on vinyl leads to a warmer, richer sound”. Arnardóttir agrees but seemingly experiences it on a much deeper level: “It feels like I am in a closer relationship with the sound waves and the vibration when I use analogue technology […] it seeps through my ears and skin to vibrate and massage my inner landscape, blood cells and neurons, gut and lungs.”