Boston’s memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, which sensitively depicts African American soldiers who fought for the Union in the Civil War, is the nation’s greatest public sculpture, in the opinion of Thayer Tolles, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s curator of American paintings and sculpture. Its creator, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, was “the most significant sculptor at the turn of the 20th century” in the US, she tells us. “He said of the Shaw memorial: ‘A sculptor’s work endures for so long that it is next to a crime for him to neglect to do everything that lies in his power to execute a result that will not be a disgrace… It is plastered up before the world to stick and stick, for centuries while man and nations pass away.’ That’s remarkably prescient given what is going on now, with monuments being looked at under a lens and beyond issues of quality to who is being depicted and where they’re located,” Tolles says.

After widespread dismay at US President Donald Trump’s initial failure to condemn white supremacists protesting against the planned removal of General Robert E. Lee’s statue in Charlottesville, Virginia, he sought to shift the debate, tweeting: “Sad to see the history and culture of our great country being ripped apart with the removal of our beautiful statues and monuments.” Yet many Confederate memorials, often erected during the Jim Crow era of racial segregation, were cheap, mass-produced and exactly the kind of disgrace that Saint-Gaudens condemned. With this in mind, we asked five specialists in American sculpture to select the pieces they regard as the nation’s truly great works.

Marcia Reiss, New York: Then and Now

George Washington, by Henry Kirke Brown, Union Square, New York, dedicated 1856

Karen Lemmey, curator of sculpture, Smithsonian AmericanArt Museum, Washington, DC

Brown was a pioneer of American sculpture. He spent four years in Italy, as many of the early American sculptors did, but left Rome with a self-appointed mission to further American monuments and sculpture. He ran around with the likes of William Cullen Bryant and became friendly with Walt Whitman, so he was part and parcel of that New York moment where they were anxious about forming a national culture.

His Washington was one of the first equestrian bronzes cast in the US. He went out on a limb and convinced a firearms foundry in Massachusetts to cast it. Brown became a model that others followed: his greatest protégé was John Quincy Adams Ward. He opened the door for Americans to train on home soil. And the bronze was such a success that it encouraged other foundries to open.

Having come from Rome, Brown looked back to Marcus Aurelius for what was going to be the definitive American monument. So there’s the absurdity in trying to put Washington on the same footing as the heroes of Europe, ancient and modern, but instead of representing him in a toga or classicised drapery, as was the tendency at the time, Brown showed the commander in chief dressed in uniform. And even though it is an equestrian monument, Washington is represented as a man of the people because his hat is off in deference to his public.

Monuments always diminish with time in terms of scale. A city grew up around the sculpture and dwarfed it. It became something other than monumental within a few decades. But after 9/11, it became a hub of communication and commemoration. People would leave candles and notices of the missing, and flowers and ephemera. I was moved to see that, despite its scale being so out of sync with the city around it. It became the epicentre, once again, for something public, for something national.

Maaarteh

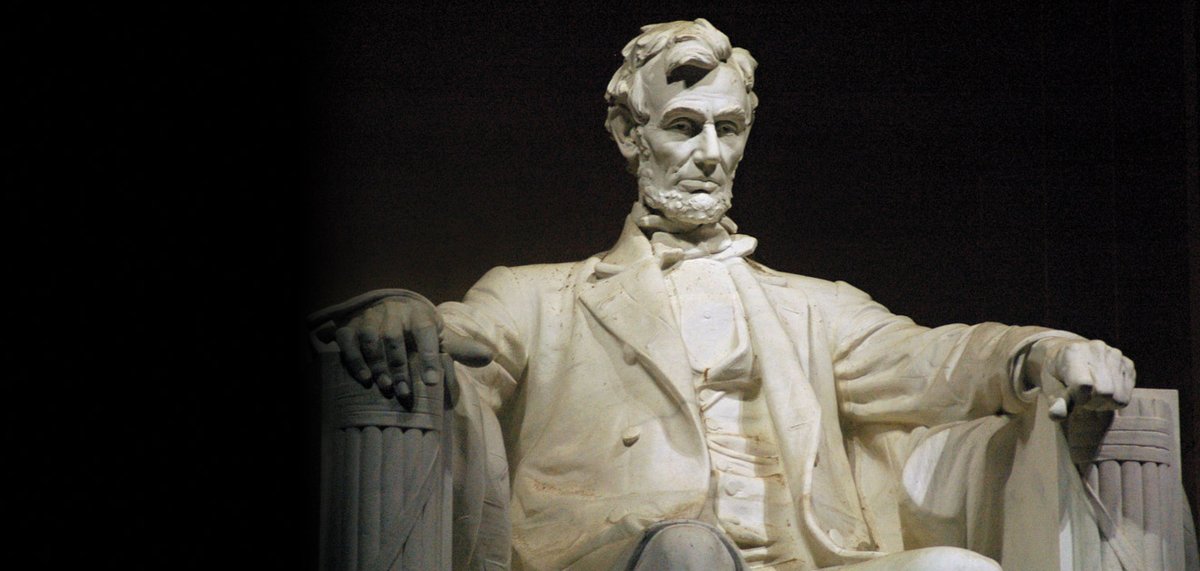

Abraham Lincoln, by Daniel Chester French, Washington, DC, dedicated 1920

Harold Holzer, historian and winner of the 2015 GilderLehrman prize for scholarly work on Abraham Lincoln

Even if French’s sculpture wasn’t the brilliant conception and great accomplishment it is, its iconic status was guaranteed because it has served as the indelible backdrop for many events, but particularly those addressing racial harmony. It has had three particularly iconic moments: Marian Anderson’s concert in 1939, Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech in 1963, and Barack Obama’s pre-inaugural appearance in January 2009. These events mark a step-by-step progression from complete segregation and hostility to people of colour to the arrival of a black American president.

The sculpture is truly colossal: 19 feet high. It’s a triumph of revision, because it was originally contracted to be just over half that. Fortunately, the architect Henry Bacon and the sculptor did several tests with plaster enlargements and photographs and determined that the scale would not work as originally conceived. The seated position is a happy accident of circumstances, artistic and political. An equestrian statue was out of the question: Lincoln was not known for his riding skills—whenever he sat on a horse, his legs tended to dangle very low to the ground, so he’d look ridiculous. Originally it was all but assumed he would be standing, but French had already done a standing figure in Nebraska, and his friend and rival Augustus Saint-Gaudens had done a standing Lincoln for Chicago. French also believed that Lincoln looked less dignified standing: he had very long legs and was indifferent about how he wore his clothes. He thought having him in a chair of state would communicate something different.

So French did one of his frenzied maquettes in clay that captured the idea of Lincoln enthroned, inspired by Bacon’s designs for the majestic Parthenon-type temple. And he got this extraordinary pose together in his head; pigeon-toed, knees thrust forward, and head slightly bowed. Study the photographs and the paintings of Lincoln and you can see that French captures his extraordinary mix of wisdom, humour and sadness all manifested at once. Part of that is in the hands, which French modelled after existing plaster casts of Lincoln’senormous hands. They look relaxed but poised to rise to the occasion.

Tony Fischer

The Robert Gould Shaw and 54th Massachusetts Regiment Memorial, by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Boston Common, dedicated 1897

Thayer Tolles, curator of American Paintings and Sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In January 1863, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The 54th was the first African American regiment, formed that May, and Robert Gould Shaw was asked to lead it. He came from a family of staunch abolitionists and saw it as a duty to his family and his country to accept. He was 25 when he died in an assault on Fort Wagner in Charleston, and his body was thrown into a trench. The bodies of other soldiers in the regiment were thrown in on top. His family said this was how he should be buried, with his fellow soldiers.

The best public sculptures are living monuments, and this is why I truly believe that this is the greatest American sculpture ever conceived. As we are aware from what’s been going on in the past few weeks, works of art have different meanings for different audiences, and the Shaw Memorial is a piece of sculpture that was obviously incredibly resonant when it was unveiled and remains so to this day. Shaw’s family always thought of it not only as a monument to Shaw, but also to the African American soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment.He never attained a rank higher than colonel and the typical equestrian monument, where he would be spotlighted up there alone on his horse, would have been inappropriate.

Saint-Gaudens earned this commission in 1884 and it took him 13 years to complete. He was notoriously slow and perfectionistic, and this is encapsulated in how he approached this monument, with many graphite and plaster sketches, ultimately landing on the remarkable synthesis of sculpture in the round, with high-relief and low-relief sculpture. It was the first monument that individualised African Americans. He did something like 40 head studies from sitters in his studio, and within the monument there are 21 different soldiers of all ages, from the young drummer boy to more grizzled older figures. These were real human beings who were marching from Boston Common down to the ships waiting to take them to South Carolina.

When the monument underwent renovation in the early 1980s, the names of the soldiers in the 54th killed in action were inscribed on the back face of the stone setting. If there was ever a sense that this was just a memorial to Shaw, the addition of their names completely blew that notion out of the water.

Vidor

The General Robert Montgomery Memorial, St Paul’s Chapel, New York, 1777, installed 1787

Sally Webster, professor of American art, emerita at Lehman College and the Graduate Center, CUNY

Commissioned during the American Revolution, the Montgomery Memorial established a tradition in the US for the commemoration of heroes. The Continental Congress—the representatives from the 13 colonies that became the US government—gave £300 to Benjamin Franklin, the new ambassador to France, to commission a work in honour of General Richard Montgomery. And while the sculpture starts an American tradition, it is by a European artist, Jean-Jacques Caffieri, because there were no artists here—that is how young a country we were.

It is a monument to the death of a hero. Montgomery led the New York militia up to Quebec and was killed there. He was the first officer to die in the American Revolution, but more importantly he was a recruiting tool for the Congress.

The monument was exhibited in the Salon in Paris in 1777 and was meant to go to Philadelphia. But Franklin was at a loss as to what to do with it: all the ports were closed because we were at war. But he still had friends in England who got it on a ship and brought it into North Carolina. It was there throughout the conflict. Afterwards, it went north to New York.

The monument was shipped in nine parts and installed by Pierre L’Enfant, who designed the masterplan for Washington, DC. One of his first jobs was cleaning up St Paul’s—because the British had occupied New York throughout the war—and installing this monument. He put it up on the porch. It’s very modest, but how appropriate: the US was such a young country. And it’s in scale with the chapel, too. There’s something extraordinarily fitting, but totally accidental.

Dave Pape

The Minute Man, by Daniel Chester French, Concord, Massachusetts, dedicated 1875

SarahBeetham, assistant professor of art history at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

The Minute Man shows the porous relationship between fine art and commercial sculptures in the late 19th century. In the conversation about Confederate monuments, people seem shocked by how many were mass-produced. The Minute Man could have gone in the same direction, but ended up becoming something else entirely. Daniel Chester French was living in Concord, he was 23 and an unknown quantity, but he created a sculpture with a life and litheness above and beyond what he’d been asked to do. He got good advice to cast it in bronze rather than granite, and that’s the sculpture that is on the battlefield in Concord.

It’s a Revolutionary War sculpture, but connects to the Civil War. It’s cast out of melted-down Civil War cannons—there were a lot lying around in the 1870s—by a company known for making swords for Union Army officers. It was dedicated in 1875, on the 100th anniversary of the battle of Lexington and Concord. Major events commemorated this battle at the 25th, 50th and 75th anniversaries and veterans would have been present. But at the centennial, there’s no way that anyone from the original event would be there. But as the keynote speaker at the dedication, George William Curtis, looked out at the crowd, he could see Civil War veterans everywhere, and he realised what it must have been like for the men in 1775.

The commission could have been for something mundane, but French creates this young man so full of life he almost leaps off that pedestal. It becomes his calling card: nobody knew that this 23-year-old kid could come up with something like that, but he seized the moment and produced something really extraordinary.