It must have been in September of 1977—a few weeks after I had arrived at the Metropolitan Museum—that I received the invitation (I viewed it more as a summons) to lunch at 820 Fifth Avenue. Fresh from graduate school and already feeling awkward in my new position as assistant curator, I was at once excited and intimidated. Even if you were a young, aspiring academic, disinterested in the social lives of the rich and famous, and ignorant of the lore of the Museum, the Wrightsman name commanded attention. Erwin Panofsky’s 1969 study of the iconography of Titian’s paintings - required reading for every student of Renaissance art—had its origin as a series of lectures at the Institute of Fine Arts sponsored by the Wrightsmans. So, too, did Francis Haskell’s marvellous 1976 book, Rediscoveries in Art (a book I return to often). Luckily, the invitation was for an informal lunch rather than a dinner. Still, from the moment Mary and I stepped out of the cab, I felt a little like Dorothy waking in the land of Oz. But there was no need for this anxiety. A seasoned hostess able to put one at ease, Jayne was incredibly gracious, and I seem to recall in a vague way that the conversation was lively. But, honestly, who could concentrate in the elegant surroundings of the apartment, with its period parquet de Versailles oak floors and surrounded by works of art that have become stars of the European Paintings galleries. Entering the flat one was confronted with El Greco’s Christ Healing the Blind, together with George de La Tour’s sublime Penitent Magdalen, both of which the Wrightsmans donated to the Museum the next year. In the living room Vermeer’s Study of a Young Woman (donated in 1979) held company with paintings by Tiepolo—three by Giambattista and two by his son Giandomenico (one—the delightful Dance in the Country—was donated in 1980). There was also an exquisite small painting of a woman in Turkish dress by Liotard and a pair of enchanting domestic scenes by Jean François de Troy. And so on. To say nothing of the furniture, objects, ceramics and beautifully bound books.

Cecil Beaton's portrait of Jayne Wrightsman Courtesy of Keith Christiansen

It did not take many congenial dinners to realise Jayne’s extraordinary gift for putting together people who would enjoy seeing and talking to each other. Encountering the other guests was a constant reminder of her many interests. She loved the playing of Alfred Brendel and I don’t think she ever missed one of his piano concerts in Carnegie Hall. Typical of her total involvement, she also read his poetry. Another favourite was William Christie, whose promotion of French music of the 17th century touched a real chord. The one expectation at dinner was good conversation. Perhaps the most amusing moment I recall is the time one of the guests - an avid admirer of Jayne with a particular passion for porcelain - picked up the beautiful plate in front of him and flipped it over to look at the mark on the underside. As he commented on it, everyone at the table followed suit. “Well, that’s a first,” declared Jayne, laughing. Ever eager to learn yet another detail, she picked up her plate as well. This was repeated with the change of china for every course, and I think all of us left with an increased sense of privilege!

It was during the first ten years I was at the Met, when the head of the department was Sir John Pope-Hennessy, whose appointment she had championed, that I realised just how important Jayne was to the Museum and, most particularly, to the department. It was, for example, the Wrightsmans who, in 1978, stepped forward to secure Rubens’s great portrait of himself with his wife and son. It had been turned down by the Getty—a case of terrible (but for us fortunate) misjudgment, as it is unquestionably one of the two greatest works by the artist in the US (it had been let out of France in return for a donation to the Louvre of another work from the Rothschild estate). It never hung in the New York apartment, as Jayne felt the picture too important not to go directly to the museum.

Peter Paul Rubens, Self-portrait with His Wife Helena Fourment, and Their Son Frans (around 1635) Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, in honour of Sir John Pope-Hennessy, 1981. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

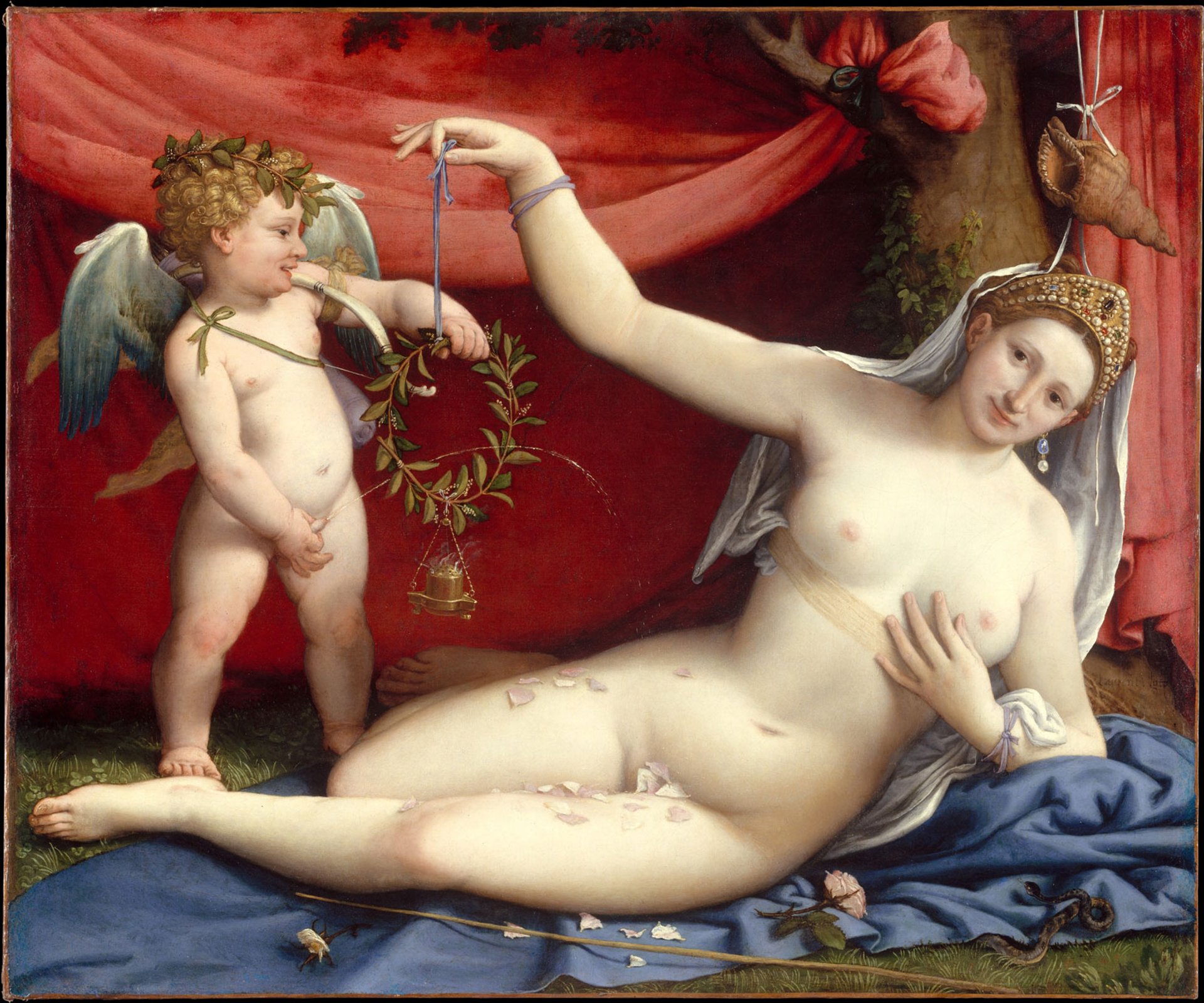

The next year, it was Guercino’s Blinding of Samson, one of the artist’s greatest paintings and the anchor of the baroque collection. The picture, previously known only from a copy, barely escaped the bombing of Beirut, where it hung in Palais Sursock. Denis Mahon, the unquestioned authority on the artist, had alerted Pope-Hennessy to the availability of the picture and he, in turn, wrote a letter to the Wrightsmans explaining its importance. They purchased it sight unseen (I can still recall the excitement of watching it unpacked). Then, in 1986, it was Lorenzo Lotto’s divine Venus and Cupid. Previously known only from a photograph and line engraving, the painting was brought to The Metropolitan to be cleaned by John Brealey, the head of paintings conservation. Offered for sale to the museum, the picture was turned down by the acquisition committee because of its price and the predictable lack of funds. It was then offered to the Getty, which—incomprehensibly—decided against it (“Not representative of the artist!” was the baffling reason I was told). We therefore had a second chance, and it was Jayne who stepped in to secure this landmark of Venetian painting for the museum. I was charged with explaining the intriguing and insouciant action of Cupid peeing through a myrtle wreath onto his mother. As might be imagined, this led me down paths I would never otherwise have explored and gave me one of the great pleasures I have had doing research. I’m happy to say that the results pleased Jayne, whose sense of irony and elevated wit was completely aligned with that found in Lotto’s unique picture.

Lorenzo Lotto, Venus and Cupid (1520s) Purchase, Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, in honor of Marietta Tree, 1986. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

During the years that Jayne was chairman of the Acquisitions Committee I had numerous occasions to discover what a discerning as well as critical eye she had. This did not mean that she was only interested in the great masterpiece by a recognised master. Numerous times it was Jayne who, with a nod of the head, let me know that she would support an acquisition one might have thought outside her interests. There was what I like to think of as the metaphysical Still-Life with Shells and a Chip-Wood Box by the Strasbourg painter Sebastian Stoskopff (a picture Morandi would have coveted). And the circular Roman Landscape with Figures that seems to prefigure Corot by the German teacher of Claude Lorraine, Goffredo Wals, as well as Philippe de Champaigne’s modest sized but grand manner Annunciation from Anne of Austria’s private oratory in the Palais Royal in Paris.

Sebastian Stoskopff, Still Life with Shells and a Chip-Wood Box (late 1620s) Wrightsman Fund, 2002. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Jayne’s retirement from the Acquisitions committee in no way lessened her interest in and support of acquisitions and, indeed, in everything related to the department’s activities. I don’t think that anything gave her greater pleasure than the re-installation of the galleries in 2013. She visited several times to see how things were progressing and after work was completed I received repeated phone calls enthusiastically informing me of the reactions of the likes of Jacob Rothschild following a visit. What a pleasure it must have been to realise the part she had played in placing The Met’s collection - finally, in the expanded galleries, fully visible - on a par with the great European collections that had formed her taste.

Remarkably, age did not seem to have any effect on her desire to elevate the Met’s collection still further. When, in 2011, I was shown at Wildenstein’s a magnificent portrait by Baron Gerard of the great diplomat Talleyrand—another work that had, for exceptional circumstances, gotten an export license from France—I turned to her, as, predictably, its price exceeded the museum’s available funds. Although increasingly fragile, Jayne (then 92) came to see it and, after careful consideration - her financial advisor later told me that her only question was “can I afford to do this?”—she bought it for the Met. “I just love that rascal,” she told me. It was another demonstration of her command of French history that she was better informed about the politics of France under Napoleon than any of us. The picture joined six other paintings she had given to form a gallery of French Neo-Classicism that is the finest in the country. And then, just two years later, she purchased for the museum a work that completely transformed the collection of French paintings of the Grand Siècle: Charles Lebrun’s portrait of the German banker Everhard Jabach and his family. It is difficult to overstate the importance of this picture and the person it depicts. For Jabach is an essential figure in the history of collecting and, through Cardinal Mazarin, played a crucial role in the formation of the Louvre’s collection. The only comparable painting by the artist, who was Louis XIV’s impresario of the arts, is an equestrian portrait in the Louvre. She followed its restoration by Michael Gallagher with intense interest, and my favourite picture of her (I have it framed, on an easel in my office) was made during a visit to the conservation studio. Jayne was not happy with the photo, remarking, “But I’m frowning.” And then, after a pause, “You must have just told me the cost of the frame!” Which we had made in Paris, patterning it after a period frame in the collection. The painting gave her enormous pleasure and she shared with me a note and caricature that Alain Gruber, a leading specialist in the decorative arts and someone who understood Jayne’s sense of humour, had created for her. It shows Jayne, dressed in rags, sitting on the steps of the Met, a tiara up for sale and a beggar’s bowl at her feet, after having spent all she had for the institution that she affectionately referred to as, “my poor relative”.

For as long as she was able, Jayne came to see exhibitions of particular interest to her. I remember Andrew Bolton taking her through the McQueen exhibition, which, being no fashion slouch herself, she thoroughly enjoyed, asking questions and interjecting observations as they made their way through the galleries. Three years later, in 2015, she was no less keen to have Wolfram Koeppe discuss the magnificent clocks on display. She had requested a wheelchair, but once in the gallery insisted on standing so that she could examine from close range the workings of the clock and the details Wolfram pointed out. Once again, the level of engagement was a joy to see. On the way back to the garage she joked with John Barelli, chief security officer, about an incident she recalled having taken place years earlier. That same year I wheeled her through the exhibition Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends. Again, there was no diminution of intense looking accompanied by witty comments about the picture or sitter—she was a gatherer of social gossip, both current and historical. In typical fashion, I learnt far more from her than she did from me - though I had made an attempt to prepare for the visit, knowing full well who it was I would be accompanying.

When she could no longer make outings, she would phone quite late at night to catch up on the news. To the last, her interest in and concern about the wellbeing of the museum remained foremost in her mind. Her passions and commitment to the museum have enriched the lives of millions. I owe her an enormous personal debt of gratitude.

- Jayne Wrightsman, born 21 October 1919, died 20 April 2019

- Keith Christiansen is the John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of the Department of European Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art where he began to work in 1977. He has organised numerous exhibitions there and has written widely on Italian painting. He has also taught at Columbia University and the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University