On 15 October 1958 Peregrine Pollen had been at Sotheby’s of London for just 11 months— working first in the Old Master department and then as assistant to the auctioneers’ charismatic chairman, Peter Wilson—when the company staged an epoch-making sale, of Impressionist and Modern paintings from the collection of the late New York banker Harold Goldschmidt.

The sale was held in the evening, for the first time in London since the 18th century, to create a sense of occasion, with attendees required to be in their place at 9.30pm and wearing black tie. Police had to hold back the crowds in New Bond Street as the actors Kirk Douglas and Anthony Quinn, the ballet star Margot Fonteyn and the writer Somerset Maugham arrived. The seven canvases—three Manets, two Cézannes, one Van Gogh, one Renoir, each of them a masterpiece—made £781,000, then the highest figure raised at a single auction session.

Six decades later, Pollen—interviewed in Katherine MacLean and Philip Hook’s Sotheby’s Maestro: Peter Wilson and the Postwar Art World (2017)—recalled the high theatre as one record after another was knocked down to Wilson’s gavel: "When Cezanne’s Garcon au gilet rouge reached £220,000, more than double the highest price ever paid at auction for a picture, Peter’s question, ‘Will nobody offer any more?’ broke the tension in the crowded room and there was a ripple of laughter."

At the end the audience cheered and stood on their chairs as if at a triumphant first night in the West End or on Broadway.

The Goldschmidt sale established art auctions as international show business. Most importantly for Pollen’s immediate future, it rewarded Wilson’s faith in Impressionism and in the untapped American market. It was the largest collection to date to be brought from the US to London for sale attracting a stream of follow-up business, expertly handled throughout the 1950s by Jake Carter, the company’s associate in New York, and encouraging Sotheby’s to set up a full-time office in the city, which the quick-witted, energetic Pollen was sent out to lead in 1960.

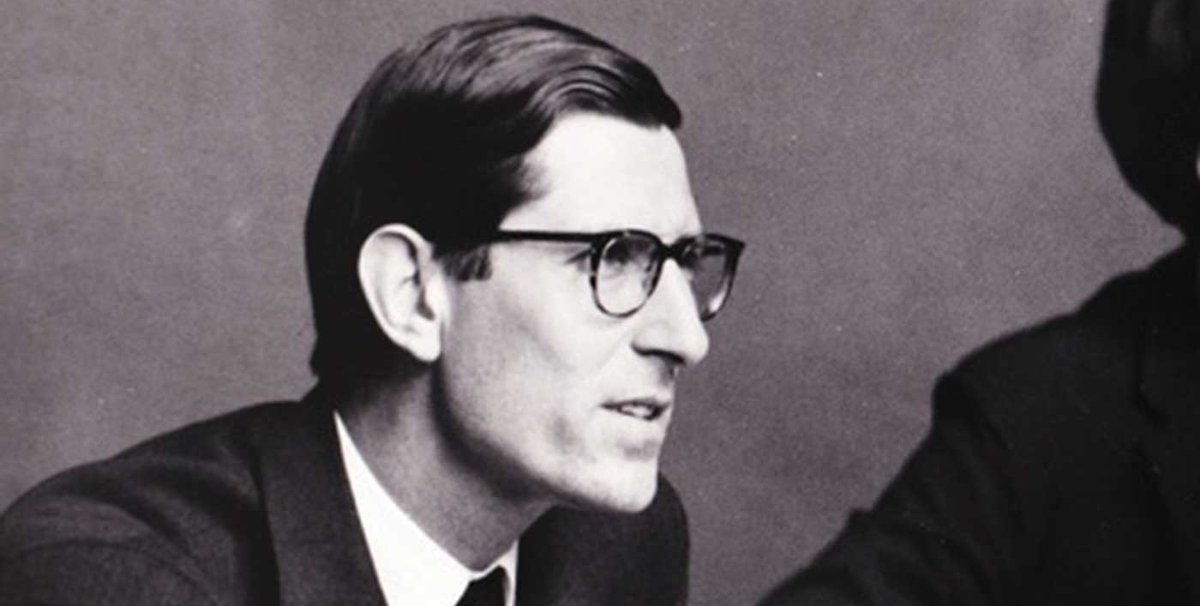

Man of action: Pollen with a German 19th-century ark Courtesy of the Pollen family

In the 1960s and 1970s, as London became the centre of the art trade and Sotheby’s and their rivals Christie’s established offices and sale rooms around the world, Pollen, Wilson’s boldest lieutenant and heir apparent, was a leader of the band of dynamic young Englishmen who revitalised the industry and laid the ground for the booming art market of the early 21st century. They led the expansion from a closely held trade between auctioneers and dealers into the theatre of spectacular sales, celebrity clients, and the large-scale fairs and markets that flourished in their wake. A key player in transforming the art world’s image in the 1960s was Stanley Clark, Peter Wilson’s head of publicity, a former features editor at Reuters and the Press Association who was as adept at devising a sexy data point on artist’s prices as he was at placing decisive coverage of a difficult takeover negotiation in the Sunday newspapers. As Ward Landrigan, the head of jewellery at Sotheby’s Los Angeles office in 1964-74, remarks in Sotheby’s Maestro: “When you got Stanley together with Peregrine and Peter, Lord help you.”

Family provenance

Pollen was born in London in 1931, the scion of generations of collectors, connoisseurs, artists and soldiers. His father, Walter (“Ben”) Hungerford Pollen, descended from Hampshire and Wiltshire squires, the chairman of steel and silk companies, and a former colonial administrator in Sudan, had been awarded the Military Cross in the First World War. His mother, Rosalind (“Lindy”) Benson, was a daughter of Robert (“Robin”) Benson, a noted collector of 14th and 15th-century Italian paintings, and a City financier who had successfully relaunched a failing family bank in the 1870s in partnership with John Cross (a few years before Cross married the novelist George Eliot) by focusing on US railway stocks and the nascent investment trust industry.

Peregrine's great grandfather John Hungerford Pollen (1820-1902) had enjoyed an intriguing portfolio career in the art world as a writer (championing Ruskin and Turner when they were out of favour), architect (of the University Church, Dublin, for John Henry Newman), artist (he joined Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris in decorating the ceiling of the Oxford Union in 1857), museum curator (helping Henry Cole build the collection at the South Kensington Museum, later the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, finding objects all over Britain and Europe), and decorator. Probably his most interesting work was that done for his cousin Theresa Cockerell and her husband, the 19th Earl of Shrewsbury—wall paintings at Alton Towers and stained glass at Ingestre Park, both in Staffordshire. But J.H. Pollen stopped short of sharing his expertise with the art market. In 1929, Peregrine’s great uncle Arthur Hungerford Pollen wrote to the young Kenneth Clark that “dealers were constantly asking [J.H. Pollen] for certification of genuineness [for furniture, woodwork, gold or silver plate] and… these overtures [principally from the Duveen brothers] never got past the stage of asking”.

Peregrine and his sister Pandora (later headmistress of Hatherop Castle School, in Gloucestershire) grew up at Norton Hall, their parents’ hospitable late-Georgian house near Chipping Campden, in Gloucestershire, where Peregrine acquired his knowledge as a naturalist and a long-lasting love of trees, tractors and bonfires. There was also a London base and a family house amid the ravishing wilderness and bird life of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides.

The Holford and Benson collections

The bookshelves at Norton contained a set of scholarly, beautifully bound volumes created by Robin Benson: the illustrated Catalogue of Italian Pictures Collected by Robert and Evelyn Benson (1914), and two catalogues created for his brother-in-law Sir George Holford, The Holford Collection at Westonbirt (1924) and The Holford Collection, Dorchester House (1927). Peregrine’s great grandfather Robert Holford, a collector of early printed books and Old Masters, and heir to a great fortune, had built first Dorchester House, a house on Park Lane, London, fit to rival the princely palaces of Rome, and then Westonbirt, a country pile near Tetbury in Gloucestershire, to house his books and showcase his remarkable collection of Old Masters, including works by Rubens, Velázquez, Van Dyck, Claude, Poussin, Salvator Rosa and Rembrandt.

Following the death of Robert’s son George in 1926, the Holford books and manuscripts were sold by Sotheby’s and the pictures by Christie’s—first in 132 lots on 15 July 1927 and then seven lots (which included five Rembrandts) at a sale in 1928, which raised £364,094, a world record for one day’s auction of pictures. The combined sales of books and pictures raised £2m. George Holford had been a sleeping partner in Benson’s bank and his death required the bank to return his capital to the Holford trustees. To replace that sum, Robert and Evelyn Benson sold the bulk of their collection, 114 canvases, en bloc to Robert Duveen for $4m in 1927, so as not to flood the auction market for the Holford sales.

The catalogues gave context to the Old Masters that Peregrine inherited from his mother, and offered a valuable grounding for his time in New York, where he found former Holford and Benson pictures among the most prized possessions of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC and other great American museums.

Collecting in the family: Duccio di Buoninsegna, The Calling of Peter and Andrew. From the collection of Pollen's grandfather Robin Benson. Acquired by Robert Duveen in 1927 National Gallery of Art, Washington

Man of action

After being schooled at Eton College, Peregrine read Modern Languages at Christ Church, Oxford, and completed National Service before working as aide de camp from 1955 to 1957 to Sir Evelyn Baring (later first Baron Howick), Governor of Kenya, at the height of the campaign to contain the Kikuyu Mau Mau rebellion. Tall, lean and athletic, Pollen had, while an undergraduate at Oxford, broken a record that had stood for a century by running a mile, rowing a mile and riding a mile (known as the Kingsley Challenge after the brother of Charles Kingsley who had first set the record) in 14 minutes. This was part of the enjoyable personal legend—a man of action from the pages of John Buchan or Jack London—that he brought to New York. Its highlights included the story of his time exploring the world before joining Sotheby’s, during which he worked at a petrol station, as a warehouseman in Los Angeles, an aluminium worker in British Columbia, a hospital attendant in Australia, a nightclub organist in Chicago, and a pantry boy on a ship from London to Las Palmas.

He had a family grounding in the appreciation and collecting of art, but also the toughness, adaptability and bright-eyed optimism to survive the hurly-burly and frontier mentality of Manhattan in the early 1960s, a city that never slept. In 1958 he was married in London to Patricia Barry, who had worked in the security services, and after the move to New York they set up house in a Park Avenue apartment with their three young children.

President of Parke-Bernet

One of Pollen’s main tasks in New York was to watch for an opening for the takeover of Parke-Bernet Galleries, which Peter Wilson had been stalking since 1947. The moment came in 1964, when the Sotheby’s office in New York was generating an annual turnover—$11m—that matched that of Parke-Bernet, and the latter faced an intractable lease negotiation on its headquarters at 980 Madison Avenue, one that could only be resolved by a new owner of the company. Alex Hillman, a New York collector, tipped Pollen off that the “PB” shareholders were ready to sell. Wilson was fired up, but the Sotheby’s partners were divided. Pollen flew back to London for a board meeting (he had been made a partner in 1961). After months of negotiations and daily conferences with Jesse Wolff, their New York counsel, Pollen saw the opportunity—the biggest in the company’s 250-year history—slipping away. Frank Hermann describes the scene in Sotheby’s: Portrait of an Auction House (1980): “[Pollen] pushed his chair back and stood up. He didn’t so much address his partners as make a speech. It was a passionate appeal to have a go. ‘And if we can't get anyone else to run PB, I’ll run it myself’, he concluded. Years later, Peter Wilson still described the moment as ‘Peregrine’s finest hour’.”

The board remained undecided, but Wilson then turned to Jim Kiddell, in Pollen’s words “the oldest partner, a world-class expert on porcelain and knowledgeable in many other categories of works of art, and most respected man at Sotheby’s”. “I believe the young people in the firm want it and it’s their future we should be thinking of,” Kiddell said. “Though I’m nearly seventy, I believe we should do it too.” The deal was saved. The negotiations continued.

The final challenge was financing. The bulk of the $1.5m purchase price was secured when Patricia Pollen acquired an introduction to a banker at Morgan Guaranty Trust. The loan was repaid out of earnings in three years.

Bright-eyed optimism: Peregrine and Patricia Pollen in New York Courtesy of Pollen family

With the deal complete, the real work began. It was cool to be British in New York—the Beatles had made their first TV appearance in the US on the Ed Sullivan show six months before, on 9 February 1964—but Pollen and his youthful team had to smooth the ruffled feathers of Parke-Bernet employees who felt they had suffered an imperial takeover. Mary Vandegrift, the head of operations at Parke-Bernet, was a lifesaver. “She was the nub of the business…” Pollen remembered. Without her the deal would not have gone through. He also had to contend, in league with Jesse Wolff, with a series of antitrust cases aimed at Sotheby’s monopoly of the New York auction market. And then there was the perennial need for more and better sales.

A sense of style

New Yorkers were struck by Pollen’s unaffected sense of style, and his ease with the local argot. And amused that this child of the British Establishment in his impeccable suits blandly ignored “such sartorial blemishes as a frayed trouser knee or rip in a dress suit”, while a colleague at Parke-Bernet described the fur collar of one of his coats as “a well-worn fibre door mat” or “a collage of shredded wheat”.

At times he took walks in Central Park with his pet South American caique, Papagoya, perched on his shoulder, chewing his ear lobes. Pollen was said to have smuggled Papagoya into the US by sedating the bird with vodka. On others he would take the afternoon off to take his children to the cinema.

Peregrine Pollen with his pet caique, Papagoya Courtesy of the Pollen family

In March 1968 an ear-splitting “baroque” rock band played at PB as the Paraphernalia fashion line put on a show of the latest line of miniskirts. “Peregrine Pollen, the gallery’s tall, gangling president, stood at the back and beamed…” Angela Taylor wrote in the New York Times. ‘Wasn’t it smashing?’ he asked. That it was.”

“In the last four years,” Lisa Hammel of the New York Times reported from a charity event at Parke-Bernet in December 1968, “[Pollen], who wore black tie, blue shirt and maroon pocket handkerchief, has changed the image of the auction from staid to fairly swinging.” When asked where the auction furniture on show the previous evening had gone, Pollen told her: ‘ “I really don’t know where it all is, it may be in a warehouse somewhere or it may be riding around New York in trucks at this very moment”.’

That insouciance was as much a part of the Pollen style as the cowboy boots he often wore, the maroon handkerchief and the pet parrot.

980 Madison Avenue

The purpose-built Parke-Bernet building at 980 Madison Avenue was a dream of flexibility compared with the rabbit warren of corridors and staircases at New Bond Street and a gift for the throwing of eye-catching events that Pollen staged to “liven things up”.

Livening things up: Pollen with his youthful team at Parke-Bernet Courtesy of the Pollen family

On one bumper evening, on 14 April 1965, a sale of Impressionists—with the third floor dressed up to resemble the Cafe de la Nouvelle Athènes in the Place Pigalle, Paris, the setting for Degas’s L’Absinthe—preceded a benefit dinner, which was followed in turn by Peter Wilson auctioning off the Philippe Dotremont collection of 43 works by Modern, mostly contemporary, French and American artists, which had been brought over from Brussels for the sale.

The following year Pollen—an accomplished pianist who taught his children to play—had his friend Philippe Entremont play Chopin before a preview of the G. David Thompson collection of 20th century art, the highlight of which was the sale of a Paul Klee canvas for a world record of $80,000.

Jewels and Hollywood became a staple of Parke-Bernet life. In 1968 Richard Burton paid $305,000 for the Krupp diamond, which he gave to his wife Elizabeth Taylor. The following year it was La Peregrina, a pearl once given by Philip II of Spain to his wife Mary Tudor, which Burton acquired for $39,000. The column inches were as important to the auctioneers as the commission on the sale.

To broaden Parke-Bernet’s reach, Pollen introduced sales for small lots selling up to $1,000. This led to the setting up of an additional auction room, PB 84 at 171 84th Street in 1968, where the lots ranged from TV sets to vintage cars and antique toys. To Pollen, PB84, with inexperienced buyers and bidding by paddle, promised to be “a great participant sport”.

1970-73: the contemporary market

Parke-Bernet sold Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Can with Peeling Label (1962) for $60,000, a world record for a living American artist, on 4 May 1970, a day when the stock market hit its lowest level since 1963. “Good art holds up even in a bad market,” Pollen remarked. And contemporary art was the future.

Just as the Goldschmidt sale of 1958 had broken the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist market wide open, so a November 1970 sale at Parke-Bernet, where James Mayor was given his head by Pollen to run a specialised sale, launched the contemporary market for a new, younger, audience. Works by Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella and Claes Oldenberg were included. “The auction is the first in which so many hot contemporary talents will be price-tested with major works at one fell swoop”, Grace Glueck wrote in the New York Times.

Pictures were consigned by well-known private collectors—including Robert and Ethel Scull of New York—and by the big contemporary dealers—Marlborough, Pace, Knoedler, Janis, Emmerich, Rubin and Castelli. “The sale became an enormous social occasion, full of the cream of New York’s young society,” James Mayor remembers in Sotheby’s Maestro, “at one stage the New York Fire department threatened to close the building because of overcrowding.”

Three years later Robert Scull, a taxicab mogul and brilliant self-publicist, returned to Parke-Bernet to sell 50 of his best Pop and Abstract Expressionist pictures on 18 October 1973. The sale put contemporary art—and not just the work of already established stars of Pop art such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein—on the map price-wise. It was a media event, where focus was on the prices that Scull achieved, many of them between 25 and 80 times what he had paid direct to artists such as Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg or Cy Twombly only a few years before, to the particular outrage of Rauschenberg, who confronted Scull after the sale, and the protesters outside. All of which added to the media profile of the sale and definitively launched an overtly commercial market dedicated to promoting and selling contemporary art.

Return to London

By 1970, the New York operation was contributing nearly 40 per cent of Sotheby’s global turnover of $108m. Pollen returned to London as executive vice-chairman of Sotheby’s in 1972 and was one of the team of directors who oversaw new ventures—including the Sotheby’s training programme for art experts; the creation of Sotheby’s Belgravia to generate a new auction market in post-1840 collectibles and pictures—and the successful flotation of the company on the London stock market in 1977. The share issue—the first to be launched in London by a large company in three years—was oversubscribed by 26 times, with Pollen, Wilson and the Rothschild Investment Trust emerging as the largest individual shareholders.

Pollen’s return to London in 1972 was greeted as the advent of the heir apparent. He and Wilson, who had always told him “You’re going to take over from me”, were on very good terms. But that deteriorated, Pollen remembered in Sotheby’s Maestro: “I remarked to a third party, ‘I don’t think Peter will ever retire because this is his life.’ Peter quoted this back to me later, angry for some reason that I had said it. He didn’t like opposition at all and he never forgot it…”

When Wilson retired in 1980 it was not Pollen but his fellow vice-chairman David Fane, Earl of Westmorland, who succeeded him. Pollen played a straight bat to People magazine: “Whereas Peter was a one-man band, David is the conductor of an orchestra. He’s an administrator listening carefully and trying to judge the right course. For us, he was the right person at the right time.” Pollen left Sotheby’s in 1982 the year before Alfred Taubman stepped in as a white knight to prevent a takeover, and the company was re-registered in the US, bringing the affiliation dance of 1964 with Parke-Bernet full circle.

In post-Sotheby’s life, Pollen remained fascinated by the art world, retained his long-held interest in collecting English drawings and expanded his interest in minerals, shells, natural history specimens, 18th- and 19th-century watercolours, Modern and contemporary paintings and prints, and Tribal Art. He devoted years to replanting the park at Norton—some 6,000 to 8,000 trees with exotics intermingled— with its matchless view across the valley to Meon Hill, and to his work as a trustee of the National Arboretum at Westonbirt, which his cousins had given to the nation in 1956.

The Pollen Leonardo

He had large ranks of relations on both sides of his family and delighted in family lore and creative connections. Multiple threads of his life—family, artistic, professional and scholarly—had been pulled together on 21 May 1963, when an Old Masters drawing sale was held at Sotheby’s, Bond Street. Peregrine was over from New York shortly before the first of the sales of the late René Fribourg’s French furniture and porcelain, all of it shipped or flown from Fribourg’s New York house at 10 East 84th Street.

Leonardo da Vinci, Madonna del Gatto (around 1475-80), sold by Pollen's cousin the sculptor Arthur Pollen at Sotheby's in 1963 for a then world record £2,056 per square inch. A collotype reproduction made by Emery Walker, 1921

Peregrine’s sculptor cousin Arthur Pollen (1899-1968)—a friend and admirer of Henry Moore and of the poet and artist David Jones, and friend, collaborator and client with his wife Daphne Baring of the architect Edwin Lutyens—had consigned for sale a Leonardo da Vinci drawing, the most finished example of his Madonna del Gatto series. “The bidding rose swiftly”, Daphne Pollen wrote in her diary, “with only one ugly pause at about £10,000, to £19,000”. Peregrine recounted half a century later how much kudos the sale of the Pollen Leonardo had given him in Bond Street —the drawing had raised the highest price in the sale—while Stanley Clark, ever alive to a good story line for journalists (and the special value of data and lists), calculated that the miniature Madonna (2.8in x 3.5in), had raised a record price per square inch for an Old Master drawing at auction (£2,056 per sq. in). Forty-one years earlier, when Arthur’s father, Arthur Hungerford Pollen —businessman, writer and inventor of the world’s first computerised naval gun sight, and Peregrine’s great uncle—had shown the drawing to friends and art experts (the British Museum tried and failed to buy it at the time), one of the first he turned to for advice on scholarly acceptance for his drawing was Peregrine’s collector grandfather Robin Benson.

What happened to King Cophetua?

The 1883 full-sized sketch of Edward Burne-Jones's King Cophetua and the Beggarmaid, given to Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery by Pollen's uncle Rex Benson in 1947 Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

Peregrine’s grandfather Robin Benson had learned much as a collector—of 14th- and 15th-century Italian pictures as well as the Pre-Raphaelites—from his friend the Glaswegian industrialist William Graham (1817-85). Graham had helped Burne-Jones to sell his masterpiece, King Cophetua and the Beggarmaid (1884) to the Earl of Wharncliffe, and had acquired the final preparatory full-size watercolour sketch (1883), for himself. Benson bought the watercolour sketch in turn at a sale of some of Graham’s collection in 1886. One of Peregrine’s favourite Benson sayings was "What happened to King Cophetua?"—an expression used to silence an argument, as code for an impasse. For years the wider family had lost sight of this full-size sketch. The mystery, the impasse, was solved when the sketch was given to the Birmingham & City Art Gallery by Peregrine’s uncle Rex Benson in 1947 through the National Art Collections Fund. The added poignancy for Peregrine was that his great aunt Anne Pollen, a fine-featured favourite of the older “Souls” such as Adelaide Brownlow and Madeleine Wyndham, had sat to Burne-Jones for a full-face drawing of the head of the Beggarmaid on 22 June 1880—“I am to come again and be painted into the big picture in a month or so,” she wrote in her diary—a year before she took the veil as a Sacred Heart nun.

Peregrine and Patricia Pollen (who died in 2016) had two daughters and a son. The couple had divorced in 1972 but remarried in 1978. He also had a son and a daughter with Amanda Willis, a dealer in antiquarian books. He was devoted to all his children, and they returned that affection— the eldest, Susannah Pollen, is a leading art adviser; Bella a novelist and memoirist; Marcus a business consultant and head of a steel business; Josh a fermentation chef; and Lally a student.

His blue eyes, welcoming, inquiring smile, and dazzling style were undimmed to the end. Even when failing hearing made it difficult he was still a fascinating conversationalist and the ideal companion at an exhibition. Living up to his memorable first name, he remained the wandering exotic falcon he always had been.

Peregrine Michael Hungerford Pollen, born 24 January 1931, died 18 February 2020