A tell-all book by the curator and art historian Matthew Israel takes readers on a year-long ride through the art world, from the heady hights of auction houses and art advisors to the practical matters of studios and shipping. In the book Israel stresses that the term “time capsule” has repeatedly come to mind while working on it. “How will this snapshot of the art world look from a distance of five, ten, 20 or even 30 years? I wonder who will still be in their jobs and who will not.”

But his account already feels like a relic from a bygone era—the frenzied, ego-driven art world before the Covid-19 pandemic struck. A Year in the Art World will give some indication at least of what life was like in the fast lane of the pre-coronavirus art circus. Here are three nuggets from the new book.

How fabricators operate—and why Jeff Koons is difficult to please

Israel boldly ventures into the word of art fabrication, “a blanket term for the various businesses that aid artists in the creation of large-scale or complex sculptures outside of their studios,” explains the author. He meets Ted Lawson, owner of the Long Island-based fabrication firm Prototype, which has worked with artists such as Yoko Ono, Mariko Mori and Ghada Amer.

Lawson gives plenty of insights into why and how fabricators operate, saying that there are two scenarios; the first involves working with mostly conceptual artists who have financial backing but “simply don’t know how to make it”. The other scenario is “when a painter is having a ‘moment’, and reaches a point in their career where they want to try making sculpture, in order to be seen as something more than a painter”.

Lawson shares lots of anecdotes about working as a young assistant in the studio of Jeff Koons where he started off “very young, very ambitious”. He tells Israel “the story of a model for a large-scale bowl he worked on for Koons that became a kind of never-ending project and testament to Koons’ processes”. Koons kept changing the rim of the bowl, fastidiously checking the measurement to the nearest millimetre. “And you'd be like, what are we going on here? And then you'd realise, this is not about even perfection anymore. This is a kind of a thing. Who knows what it’s about for Jeff? Maybe it’s sadism or holding the market back… or perfection.”

How an art advisor sees the world—and why uber-collector Yusaku Maezawa matters

In the section on art advisors, Israel interviews Berlin-born Marta Gnyp who, he says, “is unusual in that she is not just an advisor but a PhD art historian and an art collector, and in recent years she has become a gallerist”. Gnyp has written a number of books, including The Shift: Art and the Rise to Power of Contemporary Collectors, and works with only a few collectors, mostly in Europe and the US (all anonymous). “She gets paid by commissions from sold works—typically, for advisors, this means 5 to 10 per cent of the sale price,” Israel writes.

Gnyp cites one of the first art advisors, Thea Westreich, as an inspiration and also mentions Simon de Pury which surprises Israel as he is an auctioneer. “If there is an unusual country looking for a high-end art-related event, de Pury would jump on it. He organised, for example, a show of George Condo in Azerbaijan. He mediated a deal between a Swiss collector and Qatar,” Gnyp says.

She also singles out Japanese collector Yusaku Maezawa as an example of the new breed of young collectors bringing “an enormous amount of money and speed into the market”; in 2017, he bought a Basquiat painting at auction for $110m, with fees. Gnyp compares Maezawa to the legendary 20th-century art patron Peggy Guggenheim. “But,” she says, “there are plenty of collectors who think what he does is tacky. Why would you photograph yourself with the work that you just bought? But this kind of enthusiasm, the speed of it and the joy of it and the speculative aspect of it, this is very common for a lot of [new] collectors.”

How the artistic director of the Venice Biennale is selected—according to the 2019 post-holder Ralph Rugoff

Israel’s rigorous and detailed discussion on the status of biennials compares these prestigious large-scale, non-commercial exhibitions with art fairs. “The value of biennials should also be recognised in comparison with art fairs, which serve a different, commercial purpose but increasingly do include curated sections. In short, the best biennials blow art fairs away in this respect, because the focus of a biennial is so plainly on curating the work and the experience,” he writes.

Israel talks to Ralph Rugoff, director of the Hayward Gallery in London, about “what it takes to curate the Venice Biennale” which the author rightly describes as “the United Nations of art exhibitions” (Rugoff oversaw the 58th Venice Biennale last year). “Interestingly, even Rugoff can offer little insight, outside of his own history as a respected curator, into why people get chosen as artistic directors,” Israel says.

“There’s no application process or election-type scenario, no hat to put your name into,” writes Israel. “It’s all a mystery,” says Rugoff who describes being summoned to Italy by the former president of the Biennale, Paolo Baratta. “Lunch in Rome sounded good, so I was happy to go; and after we had a very nice lunch, he asked me if I would be the artistic director,” Rugoff says. Israel adds: “Rugoff suspects that the choice wasn't made until after the lunch, and that the lunch was a necessary opportunity for Baratta to ‘check him out’.”

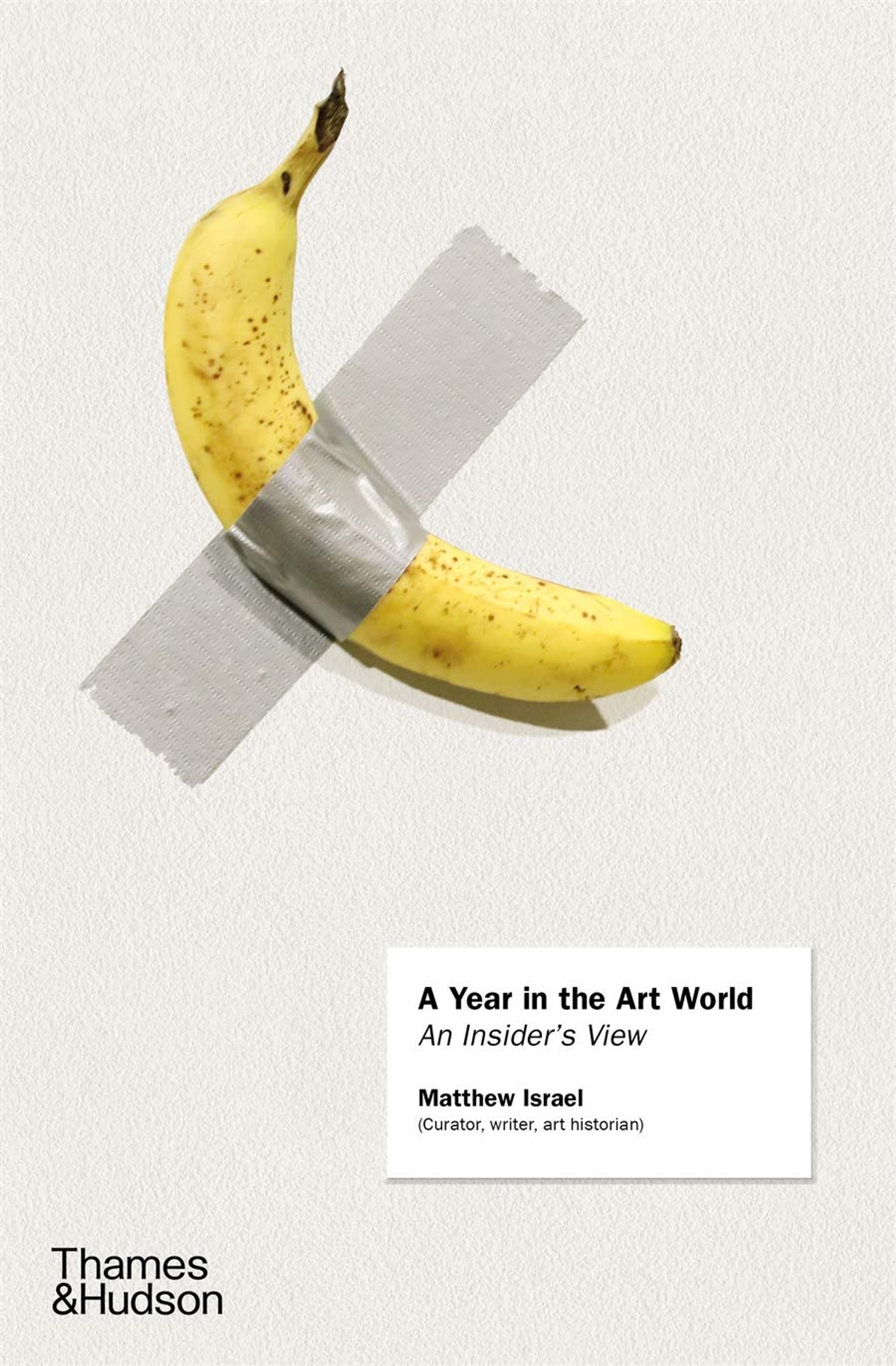

A Year in the Art World, An Insider’s View by Matthew Israel

• A Year in the Art World, An Insider’s View, Matthew Israel, Thames & Hudson, 256pp, $29.95 (hb), published in September

• Sign up to The Art Newspaper's Book Club newsletter here