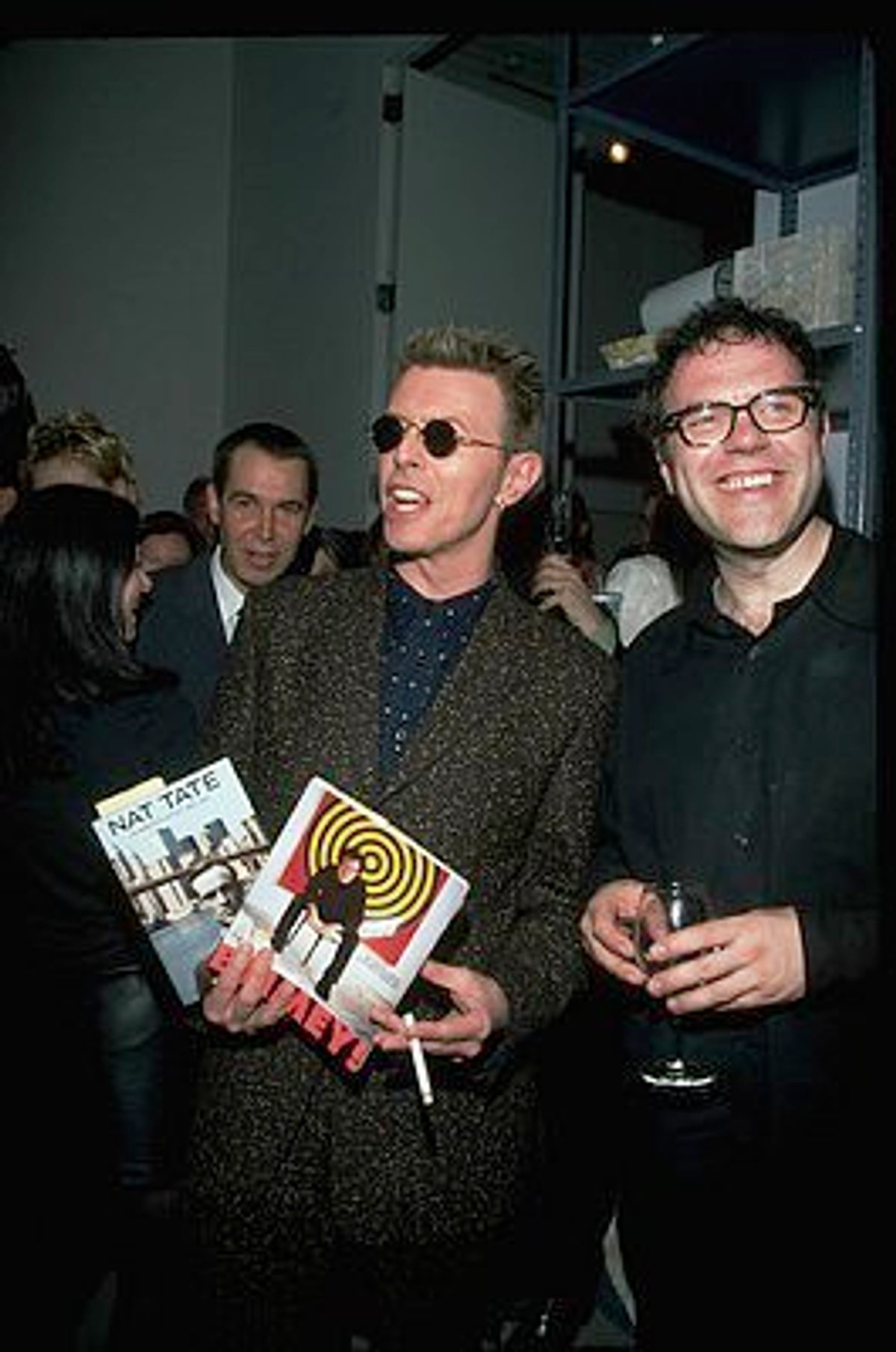

In April 1997 I had a book published by a new company formed by David Bowie called 21. The launch was at a club in New Burlington Street. I was in the middle of filming a TV series called This Is Modern Art. Because he was the glamorous host of the launch it was full of conventional-style press photographers and press and media people. It was the first time I met him. When we were introduced he said: “I’ve read everything you’ve written.” I couldn’t understand what he meant. Everything?

In those days I wrote a diary column for Modern Painters. Maybe he was referring to it. He was on the editorial board of the magazine. In my mind the book, Blimey, and the TV series This Is Modern Art, were each continuous with that column, whose purpose was anarchic comedy. Objective but understated reporting or chronicling was mixed with personal confession.

The evening included David reading aloud extracts from the book at the launch and then a dinner for about a dozen people at a restaurant off High Street Kensington. At the end he showed Emma Biggs and me a note Iman had just passed him that said, “Will you come home and sleep with me?”

I met him several times. One meeting was at his office in New York after a double launch of a book by William Boyd and one by me. He said he didn’t collect any conceptual art, instead if he was interested in something he had his assistants make up a version for him. At the launch the night before we both read extracts from my new book, It Hurts. He gave me a good tip about inflection so a malicious joke sounded milder, because the subject of the story would be in the audience. The next day we were on Charlie Rose. Charlie introduced the TV audience to my books, pronouncing Blimey “Blimmie”.

Sometimes David phoned up to chat. The first call was to report Blimey’s first thousand sales a few days after it came out. The last time I met him was at a recording studio. To get past the automated security system the man I was travelling with, Bernie Jacobson, who was one of the partners with David in the publishing company, and had been selling art to him for many years, had to answer questions from a disembodied voice about who we were looking for. Bernie had been given a codename for David but when he gave the name the voice said there was no one here called that. Eventually without any formal or polite thing being said the gate simply opened and we drove through. The place was a ranch-like set-up in the Catskills. Iman waved from a balcony. A drummer had been flown in and was recording his track in the studio. David said it was great but it should be less splashy. He pointed out Tony Visconti: Tony gave us a friendly greeting. There was a framed photo, maybe of Little Richard. David said he had it at every recording session. He showed us the view over the hills. He said it looked like the dinosaur period, pre-Man. I could easily believe it. I told him Emma and I had been painting. He said he’d been wondering if God existed.

Before I met him at the London launch for Blimey my mother told me he’d rung her up recently. I asked him about it and he said it was true. She’d written a letter to him in a breakdown addressed “David Bowie BBC”. It somehow got to the BBC and was forwarded to his management. He kindly phoned and was very calming. He told her about his schizophrenic half brother, Terry.

I was moved when he reported the Blimey sales and didn't know what to say. But then he got on to asking about other things, what kind of music I liked, and so on. All interaction with him over those years was pretty giddy. I was grateful to him because I was pleased with what I wrote in Blimey and it was a surprise to find that sort of thing could be popular, to see people on the tube reading it. David calming my mother down and laughing on the phone to me at news that a current super group’s stage design had gone wrong in a concert the other day was the height of a heady time generally for me. I was sure I shouldn’t take any of it seriously or it would all collapse.