Things got heated on 9 September. Overseas viewers who tuned in to that quintessentially British ritual, the BBC’s Last Night of the Proms, heard a sour note in this normally genial occasion. Protesters against Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union (EU) distributed 7,000 EU flags among the audience in London’s Royal Albert Hall, so that they could signal their objection to Brexit. This year’s Proms had already become politicised, with the enforced removal of large EU flags at one concert, a provocative encore at another of the EU anthem, Beethoven’s Ode to Joy, and a speech by the conductor Daniel Barenboim warning against “isolationist tendencies” at a third.

The Last Night of the Proms is supposed to be a celebration of Britishness. But this year there is a crisis of national identity, as people in the arts confront the cruel act of self-harm that Brexit represents. Last year’s Leave vote in the EU referendum divided the country and threatened the unity of the UK. It also revealed a cultural fault-line, between the young and the educated who saw the advantages of membership of the EU, and older and less privileged people who felt excluded and used the referendum as a form of protest.

Ninety-six per cent of the membership of the Creative Industries Federation (CIF), which is the nearest thing the UK has to a representative body of cultural workers, voted Remain. They could see the benefits of membership of Creative Europe, which brought £37m in arts funding to the UK between 2007 and 2012. They understood the advantages of the Erasmus international student-exchange programme and recognised the EU’s contribution to cultural regeneration.

Culture has hardly featured during the year-long limbo that has followed the Brexit vote, and it is only now that a minority government is beginning to work out what its idea of the future might be. We have heard nothing useful on Brexit from the notoriously invisible and inaudible secretary of state for culture, Karen Bradley.

According to John Kampfner, the CIF’s chief executive, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport is aware of the threat to the creative industries, but the Department for Exiting the European Union, and the Home Office, which handles immigration, “completely don’t get” the cultural sector.

The CIF is campaigning hard to protect the interests of the fastest-growing area of the UK economy. It is mounting a series of seminars around the country exploring the issues that cause most anxiety. Of these, the security of EU nationals living in Britain and the ability of British talent to move freely abroad are the most pressing—a view shared by Arts Council England, whose new chairman, Nicholas Serota, told me: “We have to be able to continue employing people from the EU, to ensure the richness and complexity of our cultural offer.” The UK is the third largest exporter of cultural goods and services in the world, and last year, Arts Council-funded organisations earned £57.5m from abroad.

The immigration rules for non-EU artists are already a nightmare. Kampfner thinks that while celebrities may be able to come and go, it will be much harder for young people who want to study in Britain, or who come to the country to work in start-ups and then move on to bigger things. “People don’t want to work in a country where they are merely tolerated. The issue is the seed corn,” he says.

The British Council, which is responsible for overseas cultural relations, has joined in with advice to both sides in the Brexit negotiations, following a consultation with more than 500 cultural, scientific and educational leaders across Europe. It recommends protection for existing schemes and more, not less, international co-operation.

As Serota says, “the devil is now in the detail of regulation”, as the fiendishly difficult task of disentanglement begins. However, “the overarching issue remains psychological. Culture and society thrive when they are diverse, contradictory, challenging and unpredictable. They wither when they are narrow, pure and inward-looking.”

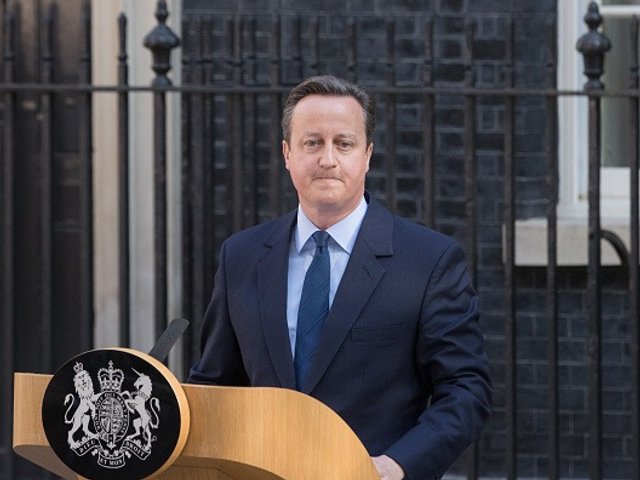

“The real business of Brexit begins now, from September to March,” Kampfner says, but damage has been done already, argues Ed Vaizey, the pro-Remain arts minister who lost his job in prime minister Theresa May’s reshuffle shortly after the referendum. “We will be more inward-looking and narrow-minded. A lot of harm was done by Mrs May’s adoption of a hard Brexit position,” he says. Vaizey hopes that the current talk of a transitional period will give time for reflection. Brexit is going to happen, he says, but “we need time to limit the significant damage being done”.

The fear is that this will lead to another limbo, half in and half out of the EU, while the divisions in society deepen. It will be a long time before Beethoven’s Ode to Joy ceases to sound, for many, like a requiem.

• The writer is a cultural historian whose book, Cultural Capital: the Rise and Fall of Creative Britain, is published by Verso