“What is the theatre of Fo if not a political message disguised, encoded, hidden beneath a great satirical talent?” So asked the Italian critic Cesare Garboli when Dario Fo was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1997. Art and activism—and the consequent controversy and censorship—are inseparable in the biography of the playwright, who died, aged 90, on 13 October.

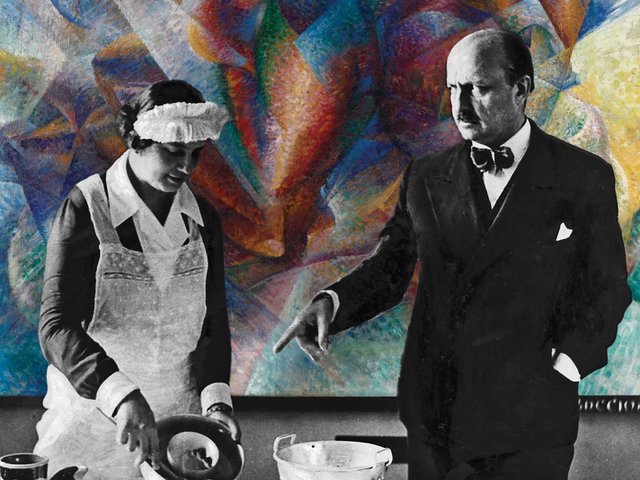

Born in Lombardy, Italy, to a modest family and blessed with the gift of curiosity, Fo studied at Milan’s fine arts academy, the Accademia di Brera. In the early 1950s he began to write satire for state television and, with Franca Rame, whom he married in 1954, to stage plays inspired by popular comic traditions. Fo’s satirical brio also found a voice in a continuous stream of set designs, costumes, puppets, drawings and paintings, to which the Palazzo Reale in Milan dedicated a major exhibition in 2012.

Fluent in grammelot As a playwright, director and actor—for years he was Italy’s most renowned theatre writer—Fo revived the role of Medieval jester. Mistero buffo (Comical mystery) (1969), a reworking of historical texts from the Po valley threaded with allusions to the present, is the masterpiece that best epitomises his theatre. His study of popular culture taught him to question the distinctions between high and low, comedy and tragedy, and to trust in the expressiveness of other languages. He popularised “grammelot”, a gibberish of inarticulate sounds that, he said, are “so onomatopoeic and allusive in their cadences and inflections as to allow you to grasp the meaning of the whole”.

Fo often grappled with censorship and, in the 1970s, raised the level of protest in his work, staging his plays in alternative spaces outside the official theatre circuits. It was not a good decade for Italy, nor the Fo-Rame company. It became public knowledge that the left-leaning Fo had enlisted in the army of Mussolini’s Salo Republic in 1943. And in 1973, in the middle of Italy’s “Years of Lead”, Rame was kidnapped and raped by five far-right militants.

Fo would confess to having joined Mussolini’s ill-fated final adventure out of fear, but in that, as in his subsequent activism, there was but one motive: rebellion. Fo’s aversion to the system saw him consistently defend opinions that were anti-capitalist and hostile to the West. In recent years, he supported the Five Star Movement founded by the comedian Beppe Grillo. He assumed no shortage of controversial positions, such as his declaration that 9/11 was not an al-Qaeda attack but the outcome of a US government conspiracy.

It was Fo’s fate, or rather his role, to be divisive, as the stir caused by his 1997 Nobel prize demonstrated. Even Fo’s kind colleague Carmelo Bene, the avant-garde writer and director, called the award absurd. The Italian political Right cried scandal while the Vatican newspaper the Osservatore Romano deplored the “cultural blasphemy”. Yet the Spanish writer Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, cheered the consecration of an anarchist, while Umberto Eco took pleasure in a prize that delivered a slap in the face to the academic world’s conventions and presumptions. If we take the long view, though, it is clear that Fo’s work places him in a tradition alongside Teofilo Folengo, Ruzzante, Pietro Aretino and all the other nonconformists and marginals since the 16th century who embody the vital, unpredictable impulse in Italian literature.

Howling at hypocrisy Fo spent his life whipping up jolly storms, claiming “freedom of opinion and happiness of existence through rage and laughter” (La Repubblica, 12 October 1997). And who knows—he may well be laughing now, having succeeded, even after death, in unmasking the classic Italian vice of hypocrisy. I write this as a native of a bizarre country, where high culture never deigns to laugh; and yet it is funny to reread the anti-Nobel award fulminations of Milan’s city officials: “Stay a jester: Milan doesn’t owe you a celebration” (La Repubblica, 14 October 1997). Just weeks ago, the same city, proclaiming its civic grief, bestowed on the fool-ideologist a funeral service on the parvis of the Duomo and a farewell spectacle broadcast live on national TV: how comic the mysteries of Italy!

• Dario Fo, born 24 March 1926, died 13 October 2016