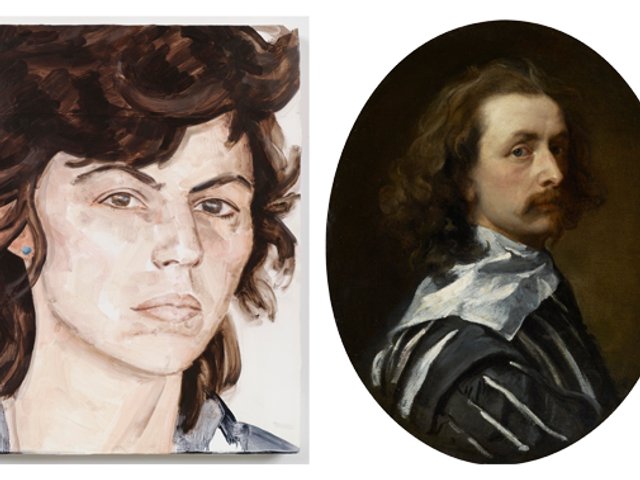

Singling out the top figurative painters of today is a bold move for any institution. Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium at the Whitechapel Gallery (until 10 May; tickets £9.50, concessions available) takes the temperature of painting in 2020 by selecting ten painters who “represent the body in experimental and expressive ways”, the organisers say. In the age of video and the internet onslaught, the death of painting has long been anticipated. But curators at the Whitechapel adroitly point out that in today’s super-fast disposable society, “the slow process of painting the figure is at odds with our instantaneous culture of taking, editing and sharing images.” Sanya Kantarovsky of Russia paints unsettling and unapologetic scenes depicting figures in dysfunctional relationships. In Deprivation (2018), for instance, a male figure tightly grips the hand of a reclining woman, reflecting an uneasy power dynamic. Kenyan-born Michael Armitage’s intimate representation of two men kissing beneath a frieze with scenes of firing squads (Kampala Suburb, 2014) is another highlight as are the US artists Christina Quarles and Tschabalala Self, all of whom take the ancient medium into exciting new directions.

British Baroque: Power and Illusion (until 19 April; tickets £16, concessions available) at Tate Britain seems prescient in the post-Brexit age, focusing on events such as the Union of England and Scotland (1707) and the Revolution of 1688-9 which gave the “political elite” in Parliament even more power. The show, surprisingly the first exhibition to focus on baroque culture in Britain, covers the reigns of the last Stuart monarchs, from the restoration of Charles II in 1660 to the death of Queen Anne in 1714 (immortalised by Olivia Colman in the film The Favourite). Most works on show revel in excess; Jacob Huysmans’ portrait of James, Duke of Monmouth as St John the Baptist (around 1662-65) presents Charles II’s illegitimate son as a forlorn, camp shepherd while Antonio Verrio’s The Sea Triumph of Charles II (around 1674) depicts the slight god-like monarch as Neptune, the mythical god of the sea. A room filled with the Hampton Court Beauties (1690-1)—a set of eight full-length portraits parading the most beautiful women at the court of Mary II—is a show-stopping centrepiece. The most intriguing section explores “illusion and deception” through a series of trompe l’oeil works which try to trick the eye (don’t be fooled though by the bizarre perspective paintings of Samuel van Hoogstraten).

It's your last chance to see On Venus, Patrick Staff’s unnerving site-specific installation at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery (until 9 Feburary; free), which dwells on earthly horrors and human suffering. Staff aims to disorient, whether by using mirrored floors to reflect the gallery's harsh yellow lighting or by installing ceiling pipes from which corrosive acid steadily drips down into steel barrels. Acid is further used to etch onto large metal plates the front pages of various tabloids that published false claims stating that the convicted child killer Ian Huntley was sexually transitioning in prison. These works bring an uneasy awareness to how certain bodies and identities are "othered" and accordingly vilified, an idea pushed even further by two video works shown on a loop. The first consists of harrowing footage of industrial animal farming practices in which creatures are beaten, skinned, pulverised and harvested for their organs and hormones. The second shows a written poem that imagines a life on Venus—a harsh, alien landscape completely free from human oppression. For those whose existences are validated and protected, living in this strange environment might seem like a scary choice. But for others, life on another planet may be a better alternative to one on earth.