In 1963, Jimmie Mannas made a photograph titled Mama, 139 West 117 Street, Apt. 4E, Harlem. In the image, a Black woman is framed by darkness, perhaps in a doorway. She’s dressed in a black coat, her figure punctuated by the whiteness of her lapel, the cloud of her hair and the shining surfaces of her face.

It is the look on her face that catches the eye. Her features are drawn toward the well of shadow at the bridge of her nose, as if in consternation. But her gaze skirts the camera, fixed on her own object, which remains outside the frame. Whose mama is she? The photographer’s? Maybe. The closely cropped image withholds details of occasion or place, its planes of light and darkness courting abstraction. In any case, the woman is kin.

Mannas was just 22 years old when he took the photo. That year, he and several others formed the Kamoinge Workshop, a collective of Black photographers that aimed to support one another through informal mentorship and collaborative exhibitions, portfolios and publications. They took their name from a word in the Kikuyu language of Kenya, meaning a group of people acting together. They shared a commitment to photography as an art form and a desire to chronicle the richness and range of Black life in the face of pervasive anti-Blackness.

Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop at the Whitney Museum of American Art presents 140 black-and-white photographs by the group’s early members. In images of daily life in Harlem, jazz music, global scenes of the African diaspora and the civil rights movement in America, Working Together shows the photographers’ formal intelligence, their intimacy with Black culture and expression and their avowal of kinship.

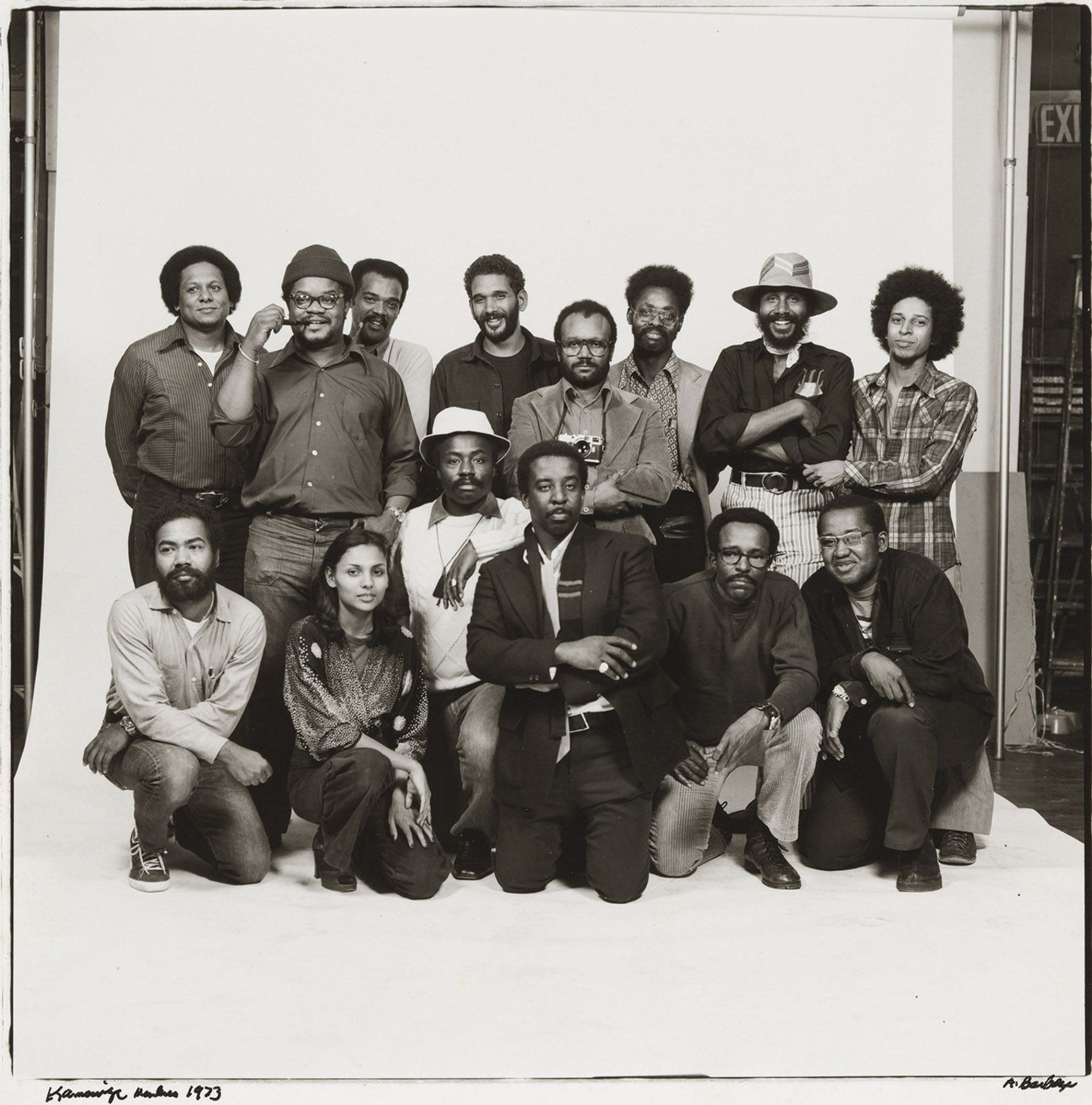

At the entrance is a large portrait of the ensemble whose work appears in the exhibition: Anthony Barboza, Adger Cowans, Daniel Dawson, Louis Draper, Al Fennar, Ray Francis, Herman Howard, Jimmie Mannas, Herb Randall, Herb Robinson, Beuford Smith, Ming Smith, Shawn Walker and Calvin Wilson. The image, taken by Barboza in 1973, attests to the camaraderie and singular self-expressions among this group of men—and one woman, Ming Smith, who joined Kamoinge that year. Encountering their work in the galleries—uniformly mounted, modestly scaled and yet revealing an astonishing range of tenderness, lyricism and critique—you might wonder: why don’t I know these photographers’ names?

While the group, still active today, has organised many of its own exhibitions, Working Together reflects overdue recognition by white institutional gatekeepers

A whitewash

Contemporary art institutions have long excluded Black image-makers and the medium of photography itself has had a tenuous relationship to the art world. At the time Kamoinge formed, photography was associated with commercial images and rarely valued as art. Moreover, photography’s tools and practices have historically reflected widespread racial bias. Film stock and lighting practices were developed with the white subject in mind; colour printing processes relied on a light-skinned standard (the so-called Shirley Card, named for Kodak’s white model who provided the universal point of reference). Rooted in a culture of white supremacy, the medium often washed out, degraded or erased the features of dark-skinned subjects, contributing to broader failures of representation in contemporary America.

Kamoinge formed in order to nurture Black image-makers and validate Black subjects. While the group, still active today, has organised many of its own exhibitions, Working Together reflects overdue recognition by white institutional gatekeepers. Curator Sarah Eckhardt, of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, which organised the exhibit, has conducted extensive research that includes video interviews with the artists, available online. This material introduces us to the spirit and visual language of the workshop and highlights the leadership of the founding member, Louis Draper.

A group portrait, taken by Anthony Barboza in 1973, of the photographers whose work appears in the Whitney exhibition © Anthony Barboza; digital image: © Whitney Museum of American Art

The current installation stresses the group’s solidarity and mutual influence. “We became a family, not a group,” Shawn Walker recalls in an interview with Eckhardt. “We even would go out and shoot together. That’s where my mind opened up.” Mutual influence is hard to trace, but individual sensibilities do emerge in this body of work. Walker, working abroad as a photojournalist, saw connections between Black farm workers in Cuba and those in the American South. Women in the Field, Cuba (1968) signals an emerging Black global consciousness, spurred by decolonisation movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

Al Fennar was drawn to the surreal and abstract figures of Japanese post-war photography. These echo in his own high-contrast, dreamlike images. In Out of the Dark/Bowery (1967), the profile of a man appears in stark silhouette against a city wall, enigmatic but eloquent as he crosses a threshold alone. In Salt Pile (1971), the artist finds a mosaic of delicate patterns and lines in the looming mound.

Ming Smith’s images are often distinguished by a ragged black border, made by an improvised film-holder cut from cardboard, she tells Eckhardt. If the frame was born of necessity, so too were her innovations with shutter speed, movement and light, which reflect her immersion in jazz clubs—her “commitment to being in those spaces that Black people occupy”, as the film-maker Arthur Jafa puts it in a new Aperture monograph of Smith’s work.

Jazz offered a subject and a method for these artists’ own improvisations. In Sun Ra space II, New York City, New York (1978), Smith captures the musician and Afrofuturist prophet Sun Ra standing lit by a single spotlight. Like a magician, he wears a spangled turban and cape that flares around his shoulders, scattering light. That flash of light—the lifted cape, which seems to defy earthly restraint—might be a mystical encounter with the performer. But the image, which paints the ecstatic rhythms of darkness and light, is also a technical feat.

Anthony Barboza also uses light and shadow to explore interior or metaphysical states. A prolific photojournalist and fashion photographer, Barboza often plays with the symbols of glamour—gold backdrops, shimmering light—to draw out the unseen aspects of his subjects. In his portrait of Grace Jones from around 1970, Jones fills the frame with stillness, as if the photographer has found the fixed point of a centrifugal force.

Barboza also documented Kamoinge’s activities in group and individual portraits. The exhibit includes a wonderful portfolio designed by Barboza in 1972 as a gift to Kamoinge members. Barboza’s documentation suggests not only the group’s solemn purpose, but their joy in collaboration and friendship.

Affection and dignity

Working Together is a highlight among recent exhibitions in New York. It brings forward a vital lineage of photographers forging a Black aesthetic from the expressions and desires of Black communities. In particular, the exhibit points to the profound influence of Roy DeCarava on Black image-makers. DeCarava served as a mentor for Kamoinge and its first director; he is represented in the gallery by a copy of the 1955 book The Sweet Flypaper of Life, a collaboration with poet Langston Hughes. The book reflects DeCarava’s devotion to photographing Harlem in the 1950s—its hallways and playgrounds, musicians and lovers—with an eye for the tonal and expressive range of his community. His varied body of work makes visible the affection, playfulness, interiority and, above all, dignity of Black life. His impact can be seen not only in the Kamoinge Workshop, but among succeeding photographers, film-makers and painters such as Carrie Mae Weems, Dawoud Bey, Kerry James Marshall, Kahlil Joseph and Tyler Mitchell. Working Together offers a glimpse of how his legacy has spread, through illumination and abundant shadow, in Harlem and beyond.

• Working Together: the Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, until 28 March