René Magritte: The Fifth Season at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA, until 28 October) contains some of the Belgian Surrealist’s best and worst works. In other words, it poses to all visitors the unfashionable challenge, usually reserved to critics, of rationalising un-ignorable, even visceral, preferences.

The show arrays 70-odd pictures in several media, primarily from the mid 1940s through the mid 1960s. Perhaps suspecting that even the broad art public has grown too comfortable with the suave strangeness of Magritte’s best-known works, the show’s curator, Caitlin Haskell begins its rough chronology with examples of Magritte’s so-called “sunlit surrealist” and “Période vache” pictures, such as Seasickness (1948), Lyricism (1947) and The Cripple (1948), works that Luc Sante aptly described as looking “like nothing so much as the missing link between James Ensor and Zap Comix.” Painted in a slithery manner that recalls and perhaps affectionately derides Auguste Renoir, the “sunlit surrealist” canvases meanwhile frustrate appreciation in just about any terms other than aesthetic defiance.

René Magritte, Seasickness (1948) Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Charly Herscovici, Brussels

The defiance in this instance was of interwar Surrealism’s vitriolic fixation on false, repressed and self-regarding bourgeois ways of life. Having suffered in his native Belgium during the dark night of Nazi occupation, Magritte moved to make a show of painting bright, energetic, goofy pictures that 21st-century eyes see as envenomed with sour irony. The artist’s letters and statements from the period make it sound as if he sincerely wanted a cheerier pictorial idiom to exude the relief of post-war liberation, as well as a new vigour of confrontation with any and every aesthetic programme.

In style, Magritte’s least-liked paintings also recall his early hero Giorgio di Chirico’s swerve from stark vistas and haunted symbolic ensembles to ungainly pastiches of warmed-over neoclassicism. Ironically, Andre Breton, having renounced communism while Magritte was flirting with it, thought that his still-contested mid-1940s pictures gave off a whiff of Stalinist utopian emotional recipe.

Fortunately for Magritte’s reputation, and for his public, he abandoned these paintings after they failed to find favour with critics, dealers or collectors. (A catalogue contributor mentions the speculation that Magritte might have made them partly to spite a former patron who withdrew support on the baseless prospect that the artist might someday become a “bad” painter.) He resumed working in a manner that suppressed facture and permitted him to refine the investigation of pictorial illusion’s philosophical inklings.

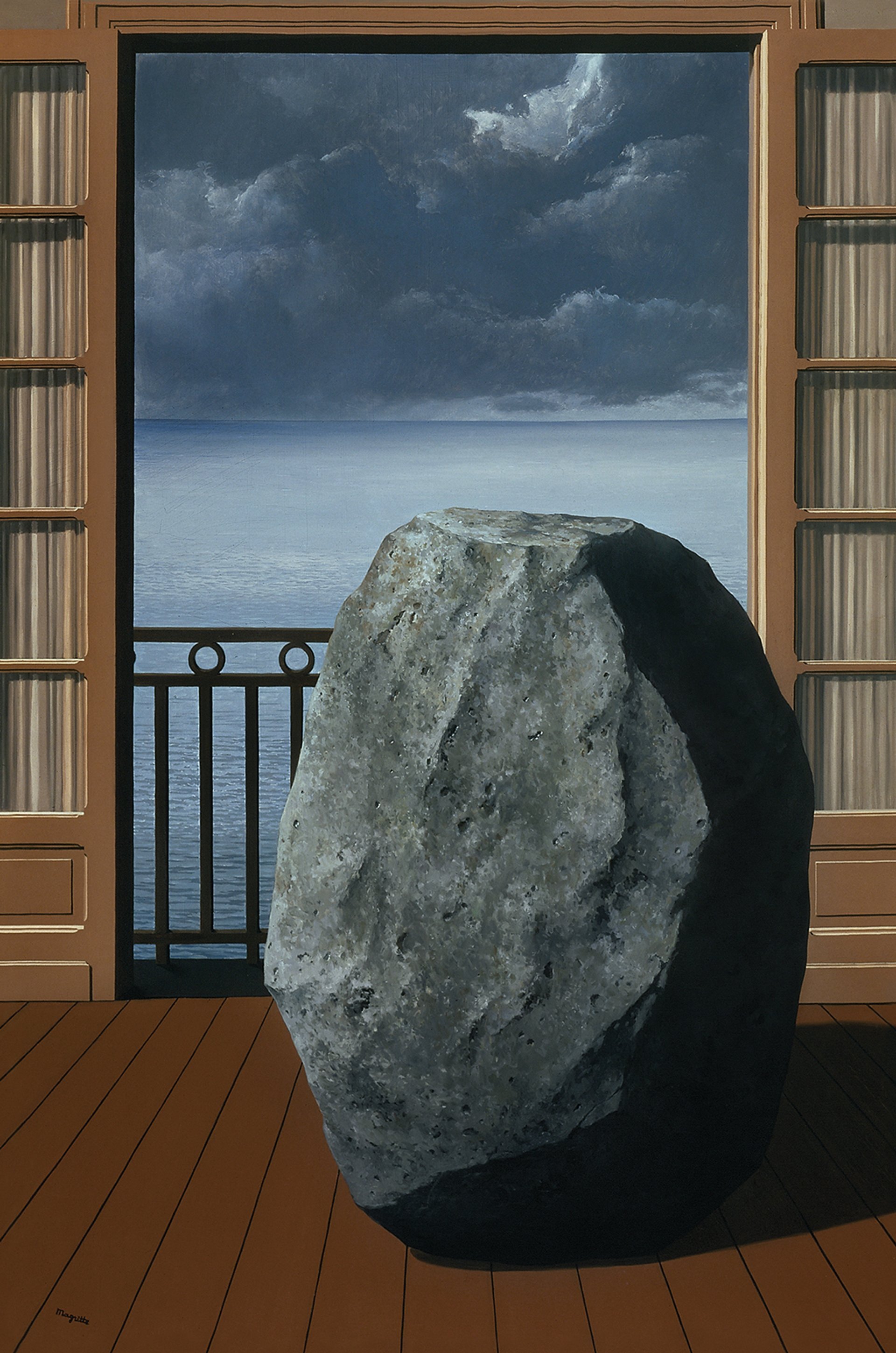

Consider the well-known late painting The Invisible World (1954), from the Menil Collection. It has first-glance plausibility: a boulder sits, crisply shadowed as if by sunlight, on a wooden floor before French doors opened to reveal a shallow balcony overlooking a becalmed sea, beneath a turbulent sky.

René Magritte, The Invisible World (1954) Photo: Charly Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

But curiosity breeds oddity. How could such a floor support so massive a stone? How can clear daylight shine within, while dark overcast looms outside? Are we seeing a small stone placed in a dollhouse room with stage scenery painted to scale behind, or a huge rock inexplicably furnishing a domestic space?

As in other pictures, such as The Glass Key (1959), another boulder perched on a mountain, and The Battle of the Argonne (1964), a pair of clouds facing each other, Magritte reminds us that substance and gravity, time of day, frame of reference, relations of time and space are among the illusions implicit in even the most banal representational paintings. Simply making them explicit can render numbingly familiar depictive conventions uncanny.

Magritte likened one of the levitating boulders that appear in his pictures to the moon. But we, having seen extraterrestrial photographs of the earth that he did not live to see, easily make the leap to viewing his hovering stones as figures for the earth’s—the world’s—own groundlessness.

SFMoMA has overplayed its stagecraft by decking the exhibition entrance with tiered curtains echoing too literally the framing motifs Magritte used in canvases such as The Human Condition (1933) and The World of Images (1950). The latter painting presents a window view through parted curtains of an orange sun setting upon a blue sea, at the dead centre of the picture, like a bullseye. The window’s lower pane has been shattered, as if by the sun’s intensity—or by the force of viewers’ absorption—and the shards fallen on the sill and floor seem to have taken with them fragments of the sunset view they made available when intact. The shards’ opacity gives away the game of the painting’s double illusion of transparency: that of the canvas as window-like and that of the window depicted.

Rene Magritte: The Fifth Season might have seemed nostalgic if we did not view it today through the quandaries about representation dramatised by Pop and conceptual art, and the painters and photographers of the so-called “pictures generation”. The artist even appears here as a craftsmanly precursor of the wildly arbitrary and lurid capacities of digital imaging and animation. SFMoMA gives an ill-advised nod to this fact with interactive displays, in a coda to the exhibition, that enable visitors to see themselves inserted into simulations of certain pictures.

Magritte’s artful paradoxes, where they do not over-invest in mystery, bring concreteness, a slow pace and friction back to our scrutiny of depiction. They reawaken, as he implied by calling himself a philosophical painter, age-old questions about what the senses apprehend, what awareness and reflection contribute, and how we know.

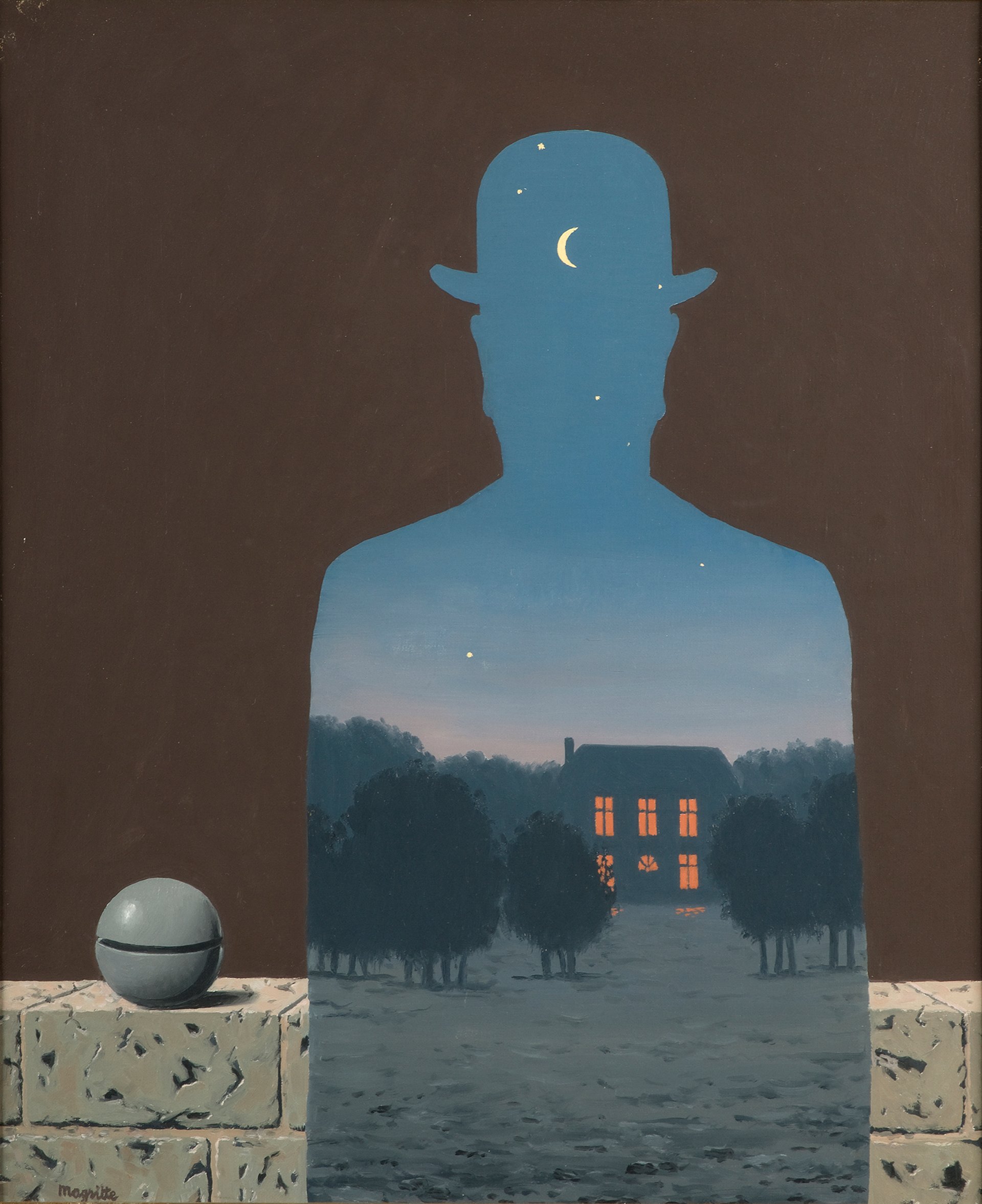

René Magritte, The Happy Donor (1966) Photo: Charly Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York