Nicholas Galanin’s mid-career survey Dear Listener (until 3 September), at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, is grounded in the artist’s experiences and heritage as a Native Alaskan. But to reduce his art to the limiting category of “identity politics” would be a mistake. The exhibition is expansive, embracing and grappling with many facets and complexities of what it means to be Native American today.

The show begins in a spacious gallery, where a photograph of the artist’s head has been blown up and split in half. Its two parts frame the doorway through which visitors must pass to get to the main display. It is not entirely unusual for the introduction to a solo show to contain a photograph of the artist, but more often than not, the image is historical and the subject is dead. Galanin, who is of Tlingit and Unangax descent, is very much alive, although his peoples have been decimated by white America. The large photograph of his face reminds visitors to the Heard, one of the top institutions in the country dedicated to Native American art, that they are not about to see more ethnographic displays of artefacts like the ones sitting in glass cases across the lobby; they are encountering contemporary art made by a practitioner in the present day.

One of the showstoppers in the exhibition of around 50 pieces, organised by the museum’s fine arts curator, Erin Joyce, is We Dreamt Deaf (2015), which greets visitors in the same entry gallery as Galanin’s photograph. On a raised platform, the front half of a taxidermy polar bear seems to crawl forward, while its back half is flattened into a rug. The animal, which has bullet holes in its side, has suffered triply at the hands of humans. Visitors accustomed to benign taxidermy displays in natural history museums will likely be unsettled by the sight of a creature trying to escape its brutal fate.

Galanin is a keen observer and critic of exploitation, especially of Native people. For White Carver (2012-present), he enlists a white man to sit on a platform behind a red velvet rope and carve a wooden “fleshlight” sex toy that resembles one made by the artist himself, titled I Looooove Your Culture (2012). The performance, which took place five times at the Heard, brilliantly satirises the way “Indian” culture has been fetishised and flips whose bodies get exhibited by whom.

The performance White Carver brilliantly satirises the way “Indian” culture has been fetishised and flips whose bodies get exhibited by whom

On adjacent walls, two sets of work are based on Galanin’s practice of buying fake Native American masks made in Indonesia, chopping them up, and reassembling the pieces to create abstract masks of his own. The artist also carries out this process in a video, Unceremonial Dance Mask, 21st century (2012), playing in the same gallery. There’s something powerful in the image of a steady and determined Galanin hacking away at the commodification of indigenous culture with a hand tool. As I watched him hold the new mask to his face and dance around a fire, I wondered if he was re-consecrating the object, skewering the ignorance of non-Native viewers, commenting on the slipperiness of authenticity, or all three.

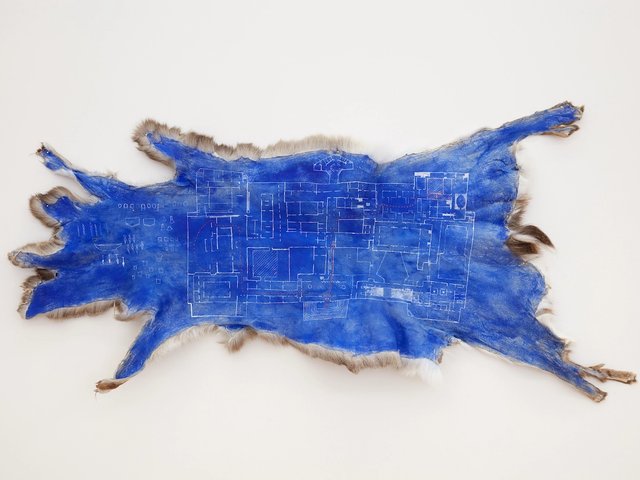

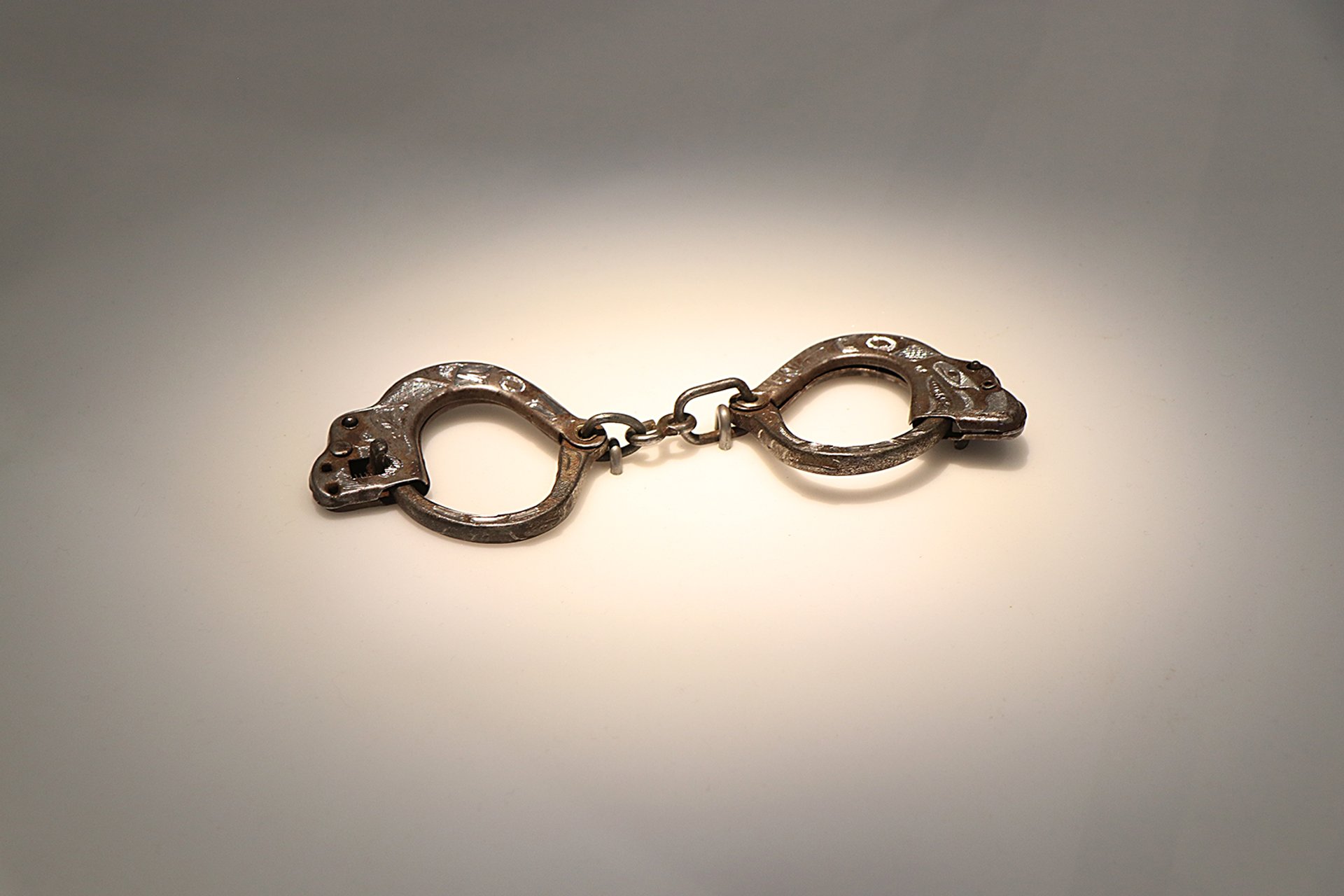

Clearly, for Galanin, it’s just as important to destroy the fake masks as it is to make something new of them. This impulse to reuse pre-existing material, no matter how offensive, runs throughout the show. In one gallery, a tiny pair of iron handcuffs lays low to the ground in a case. Galanin found the shackles, which were used in boarding schools where the US government tried to “assimilate” Native American children by stripping them of their culture. He engraved them with designs of Tlingit formline, reclaiming the oppressor’s tool. Acerbically titled Indian Children’s Bracelet (2014), the work is deeply affecting.

In one gallery, a tiny pair of iron handcuffs lays low to the ground in a case. Galanin has engraved the shackles, used in boarding schools where the US government tried to “assimilate” Native American children by stripping them of their culture, with designs of Tlingit formline, reclaiming the oppressor’s tool

Galanin often talks about his art as part of a cultural continuum, and you can feel that at the Heard: he confronts the traumatic past but does not wallow in it. He works in traditional Native arts, such as formline, and in mediums more associated with contemporary art, like video. Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan (2006)—which translates to “We will again open this container of wisdom that has been left in our care”—features a man break-dancing to a Tlingit chant. A follow-up video shows another man performing a ceremonial Tlingit dance to electronic music. In both cases, the performers’ moves appear perfectly in tune with the music of a different culture. The continuum is vast, and it is hybrid.

The show’s most beautiful expression of hybridity is No Pigs in Paradise, a collaboration between Galanin and the Canadian artist Nep Sidhu. The series honours Canadian indigenous women, who have been the targets of deadly violence for decades, with elaborate garments that are outfitted on mannequins and displayed mostly in one gallery, as if in a showroom. They are stunningly original creations—mash-ups that seem to blend high-end casual wear, punk gear, ceremonial clothing, and even, in one case, what looks like a foil emergency blanket. With titles such as She in Gold Form, She in Shadow Form, and She in Rhythm Form 7B, the works seem to evoke a pantheon of goddesses that will rise in part due to the strength bestowed on them by such carefully wrought garments.

Although the Heard’s mission is “to be the world’s pre-eminent museum for the presentation, interpretation and advancement of American Indian art,” it was founded by white collectors. It’s also not a contemporary art museum with a history of exhibiting such conceptual and political work. To an outsider, at least, Galanin’s survey feels like an act of decolonisation. I hope that visitors will, as the exhibition title beseeches them, make an effort to truly listen.

• Dear Listener: Works by Nicholas Galanin, Heard Museum, Pheonix, Arizona, until 3 September