Those of us who study Islamic art are forever beating ourselves up. What is it, really, that we are studying? People often ask this question, and we sort of know, but it’s more than religious art–or is it? Where do the boundaries begin and end? What about Indonesia? What about Brick Lane? Philosophy? Theology?

The Rise of Islamic Art, which is based on an exhibition last year at the Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon, and What is “Islamic” Art?, an academic study, represent opposing approaches. The Gulbenkian’s exhibition, drawn mainly from its own collections, with some loans from other museums, examined the macro-politics surrounding the formation of their collection. The wide-ranging museum arrangement has traditionally separated East and West, and, in this collection of essays and catalogue of the Islamic objects, a complex diaspora of Armenian dealers and collectors—which stretched across Europe and Asia—is revealed.

Gulbenkian was not merely trophy hunting but possessed a keen observation of workmanship and technology

The contributors have made an intensive study of Calouste Gulbenkian (1869-1955), the enormously rich collector, who left Istanbul in 1896 and made his fortune in oil. Money, plus the dispersal of wealth following the First World War, allowed him to purchase an array of beautiful and perfect objects of “Oriental” origin, built especially around ceramics and textiles. In these fields, the collector himself was particularly knowledgeable, arguably more so than in his purchases of Western objects.

A valuable contribution from Avinoam Shalem focuses on Baku. Shalem argues that Gulbenkian was not merely trophy hunting but possessed a keen observation of workmanship and technology. He also disperses some mythology about a potentate “more mysterious than Lawrence of Arabia”, who exuded a strange air of “oil, blood and power”, and seems to have been viewed in some quarters as a sort of Dracula of the art world.

Jessica Hallett, the curator of the Islamic side of the Gulbenkian collection, displays through significant graphs the relationship between media and acquisition. “Islamic art” is revealed as museum terminology, its acquisition keeping pace with an oil-based economy. I would be inclined to see the term “Islamic art” as connoisseurship labelling, but there is no doubt that Hallett’s clear approach shows how the subject developed in its geo-political context.

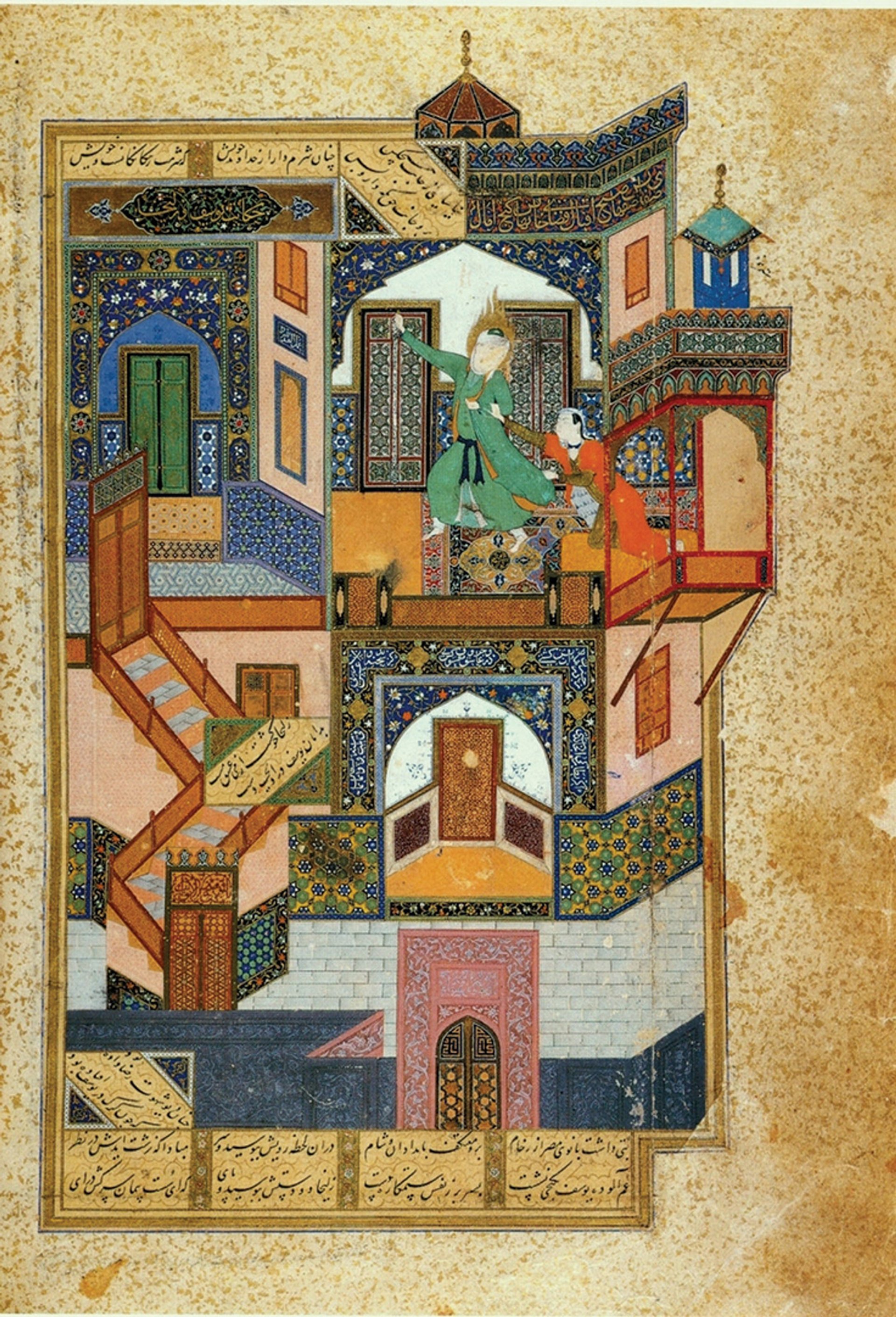

Kamal ud-din Bihzad’s The Seduction of Yusuf (1488), a miniature from a book by Sa’di, one of the greatest writers of Persian poetry Courtesy of the National Egyptian Library

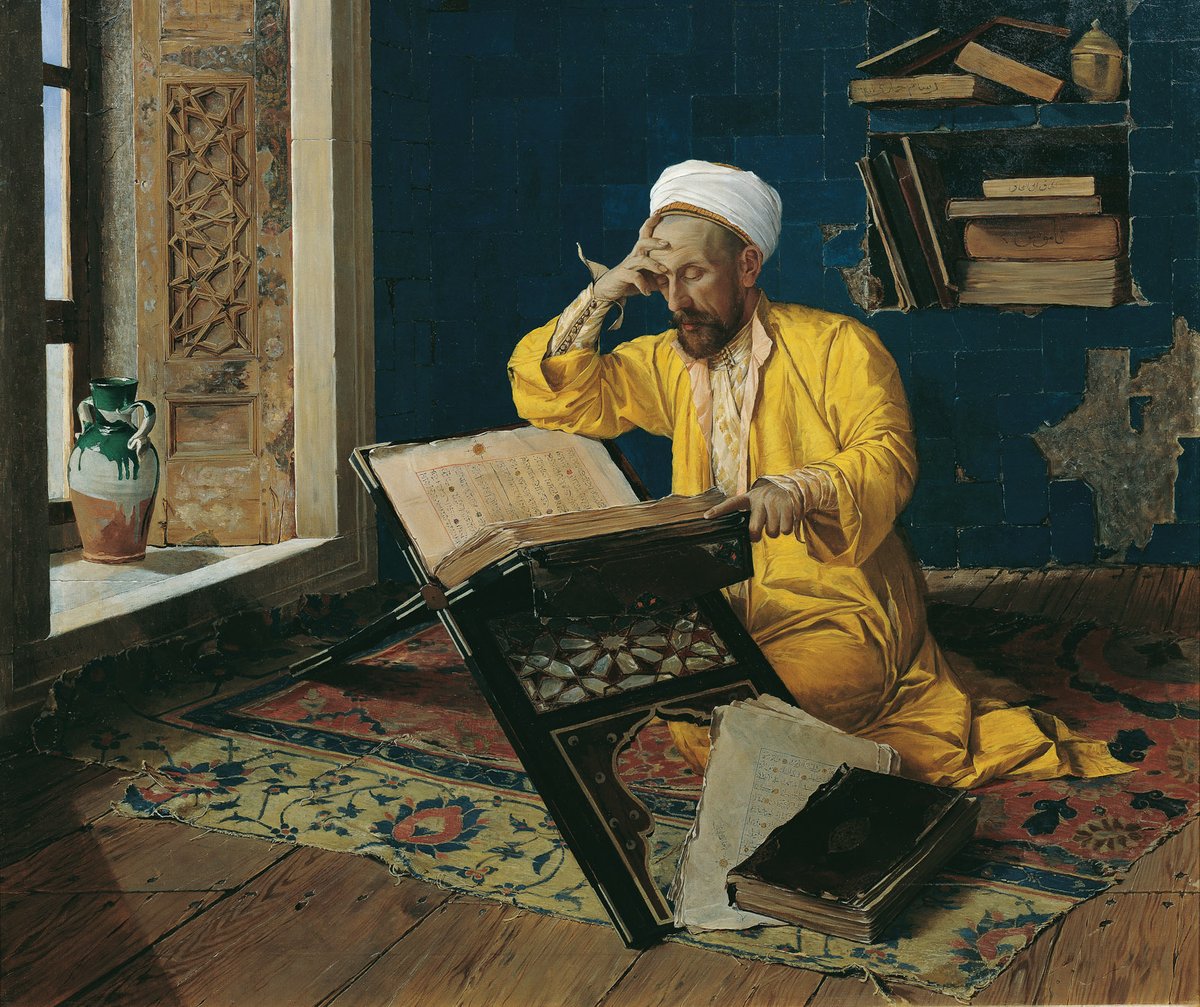

If The Rise of Islamic Art reveals a collector seemingly uninterested in Islam itself, What is “Islamic” Art? by contrast seeks to restore religious significance to works that have become detached from their original spiritual contexts. Unlike Hallett, Wendy Shaw, the professor of Islamic art history at the Free University of Berlin, is not a museum curator. Her book is an intellectual—perhaps too intellectual— examination of aspects of Islamic culture that Western commentators have detached from their profoundly religious contexts. As an example of Shaw’s approach, her scrutiny of Bihzad’s famous illumination of Joseph fleeing from the approaches of Zuleika (1488) examines it as a tectonic embodiment of Sufi mystical and poetic views of sex. As for the individuality of the artist, of course, she is quite right to note that Persian painters did not adopt the cult of celebrity, but she does not look at other works by Bihzad which would highlight his particular concern with trapezia and rectangular images. This manifests, for example, in his renderings of towels hanging in a barber’s shop, or ladders against a wall in the construction of the legendary castle of Kavarnaq (around 1494-95).

In the Joseph and Zuleika encounter, the geometric shapes form the complex system of enclosures surrounding Joseph. She also ignores the straightforward and almost-universal human reaction of seeing the walls, doors and staircases in Zuleika’s house as a sexual entrapment mechanism. The comparison she proposes with Western paintings of the same subject is illuminating, but she seems puzzled about why it was such an attractive meme for artists, East and West.

She might have considered the wishes of a patron who could have his own private sexual fantasies attended to by his court artists and might extend calligraphy in an unexpected way. It is rather hard to take seriously her straight-faced account describing Joseph’s introduction to writing alif, that is the single-stroke upright letter “a”, into other letters indicating Zuleika’s genitalia. Shaw has the same attitude towards depictions of the wondrous Simurgh, the mythical bird with dazzling feathers, and complains that it appears where it is not needed in a story. But what artist worth their salt would pass up a chance to include such a sizzling display of plumage, and who would not delight in opening a page to find it?

My comments, Shaw would doubtless say, see works of essentially Islamic art strained through the sieve of a Western epicene. Her proposed theological interpretations form important restoratives in our study of an elusive art but do not eliminate the many other ways of experiencing a cultural artefact, including the curatorial background investigated by Hallett. My advice is to read Shaw’s book for the important controversies it ferments in the subject, but keep looking at pictures, perhaps in the privacy of your own home.

• The Rise of Islamic Art, 1869-1939, Arthur Bijl et al, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, 174pp, €30 (pb)

What is “Islamic” Art? Between Religion and Perception, Wendy M.K. Shaw, Cambridge University Press, 336pp, £29.99, $39.99 (hb)

• Jane Jakeman has a doctorate in Islamic art and architectural history from St John’s College, Oxford. She has lectured on Islamic art and has travelled widely in the Middle East. She has been on the staff of the Bodleian and Ashmolean libraries and was librarian to the Oxford English Dictionary