When he was active, Joseph Beuys (1921-86) was the art star of post-war Germany. The son of a civil servant, he claimed to have survived a plane crash in Crimea while serving in the Luftwaffe during the Second World War, largely thanks to a band of wandering Tartars. With that story as a creation myth, Beuys added a hat and vest as props, and leapt into a void at the Dusseldorf Art Academy, where he became a professor.

Bueys, the documentary, premiered in Berlin last week at the Berlin International Film Festival. Directed by Andres Veiel, it draws from the huge visual archive—in Germany, Beuys was as well documented as Warhol in America—and it introduces (or reintroduces) Beuys to an audience that is more in tune with the celebrity-artists who came later.

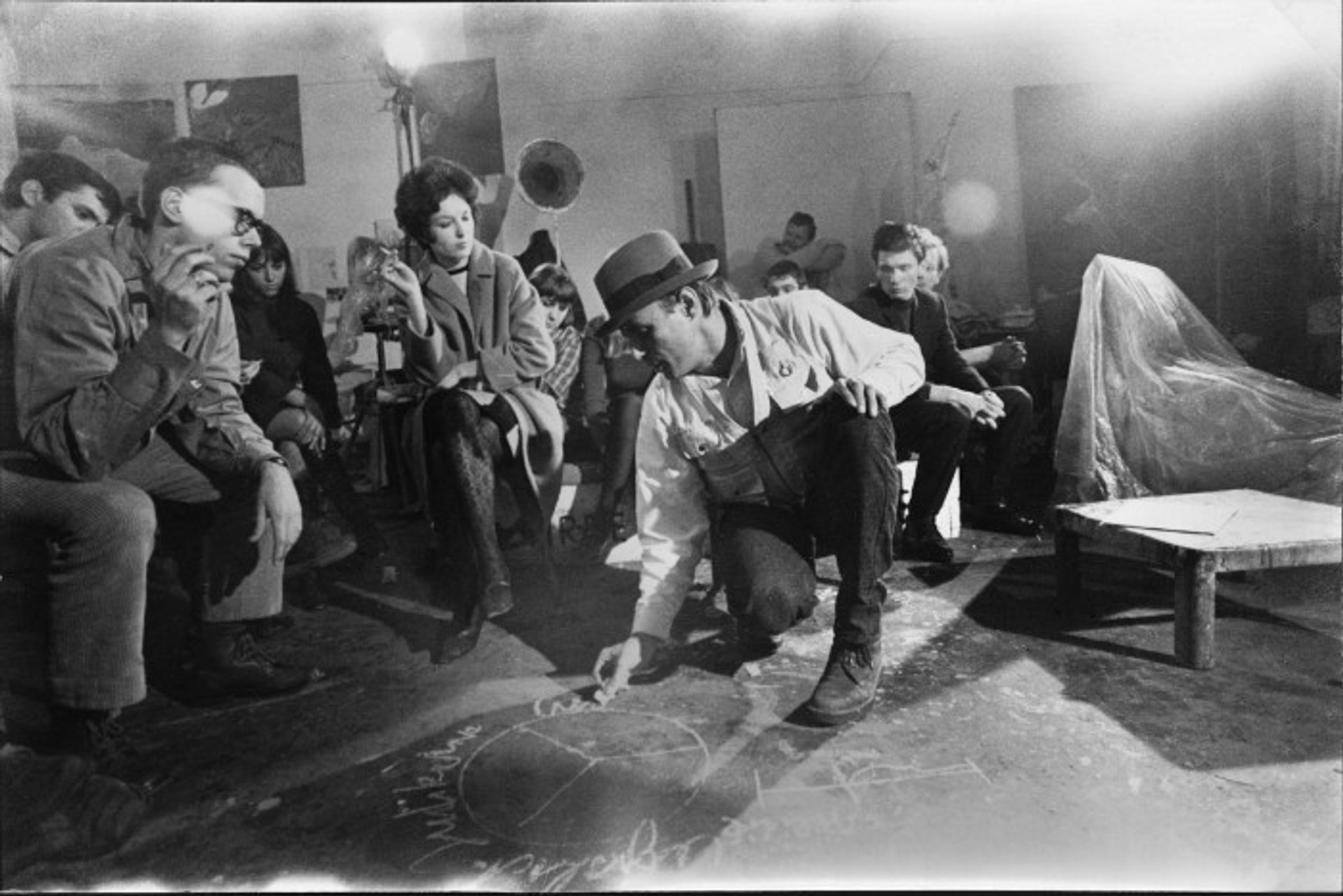

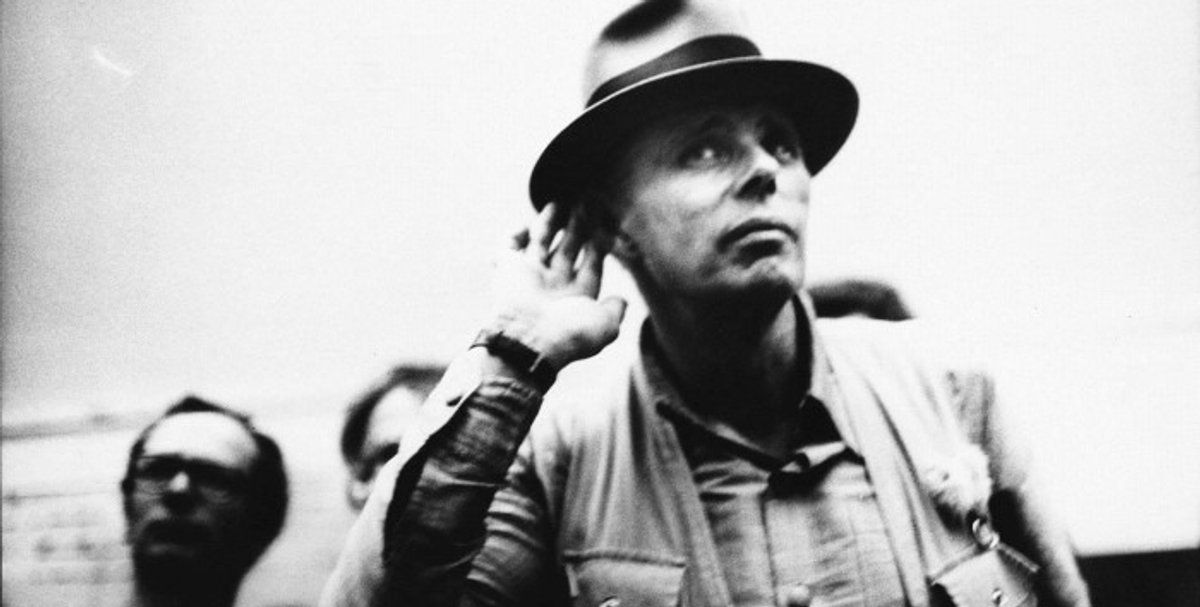

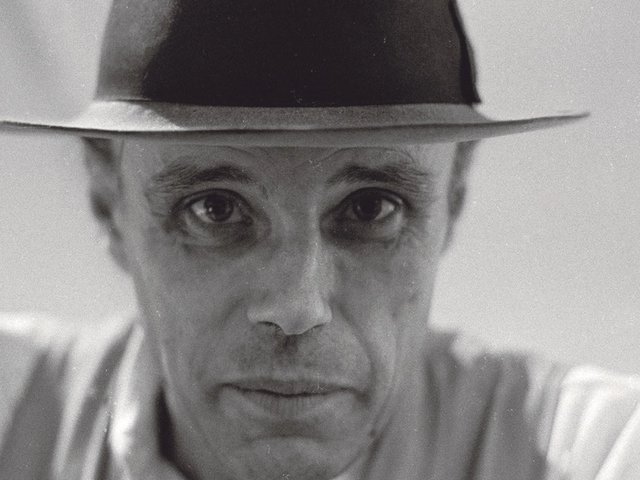

The film could be called Beuys 1.0, an attempt at a general, judicious summary of the artist’s life and career that someone encountering him for the first time could easily follow. Central to the story is his 1944 plane crash, and the film frames his survival as an event that turned the young man into something of a shaman, a notion enhanced by close-ups of his grimacing grin. That role inflamed a generation of Germany’s young artists during the 1960s and 70s, when the country was emerging from the ruins of the war, and students rallied around rebels who stood in opposition to the institutions tainted by a Nazi past.

Scorn for the art establishment also fuelled Beuys’s appeal. He delighted in creating works that were too big for any museum, like the 7000 Oaks project at Documenta 7 in 1982, which involved dragging a huge rock slab into a park in Kassel for every one of the 7,000 trees that he planted. Beuys also paraded around with a dead hare, and smeared himself in fat at events, relishing a grostesquery that he shared with Gunter Grass, another young army veteran (and Hitler Youth member) who became a cultural leader in post-war Germany. Like Grass, Beuys took his rebellious brand into politics, but charisma only went so far. The documentary shows some of his odd theories being repudiated by the Green Party, in which he was active.

Beuys is also shown to have understood the idea of branding before most in the art world did. Supposedly wrapped in felt after his crash, he appeared in a felt hat and often used the material in his work. Piles of fat, which he said the Tartars used to keep him warm, also became a regular medium. (Beuys’s wartime survival story has since been debunked.)

Stressing Beuys’s myth more than his art, the film has major gaps in tracking and contextualising his works and politics. The artist’s later years also get short shrift. Still, the documentary is the most extensive revisiting of Beuys’s art and life for a general public. As such, it will be the film of record until a new one comes along—although a dramatic retelling of Beuys’s life on the screen should not be ruled out.