A number of art films that had their premiere at the Berlinale International Film Festival this year (20 February-1 March), should soon start making their ways to theatres—depending on closures caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

In the biographic film Hidden Away (Volevo Nascondermi), Elio Germano plays Antonio Ligabue (1899-1965), Italy’s best known self-taught/naïve artist, who bounced in and out of insane asylums. In a Grand Guignol style that makes subtitles unnecessary, Germano gets his hands dirty in paint and clay and even grunts Ligabue into a romance.

The film’s director Giorgio Diritti celebrates Ligabue as a misunderstood and mistreated tactile genius, as the film piles on the clichés about artistic expression and victimhood. Fascists want to punish Ligabue. Dealers want to cheat him. All are shown to have ulterior motives except the artist hugging the farm animals. The camera lingers on Ligabue’s work, from self-portraits to jungle scenes, plus sculptures slapped together in wet clay, enough to make it likely that Ligabue’s market will rise.

Also filmed in Italy, the melodrama Pompei, directed and written by Anna Falgueres and John Shank, is set in the modern-day slums in the shadow of Vesuvius. Here, youth turned feral by poverty, scavenge for first loves and for anything to sell, evoking the despair of post-war Italian neo-realism and Luis Buñuel’s tragic story of Mexican street children, Los Olvidados (The Young and the Damned). The location being what it is, these kids sell foraged fragments of antiquities for pennies. A complex set of rules emerges behind the seeming anarchy of parentless children.

Ancient Pompeii is a perennial backdrop for sundrenched “sex and sandals” screen epics. This film, however, will test whether rebellious antiquities thieves can draw a young crowd to cinemas. The Canadian TV heart throb Aliocha Schneider in the cast should help. So should his co-star Garance Marrillier, who played a vegetarian-turned-cannibal in the 2017 gore-fest Raw.

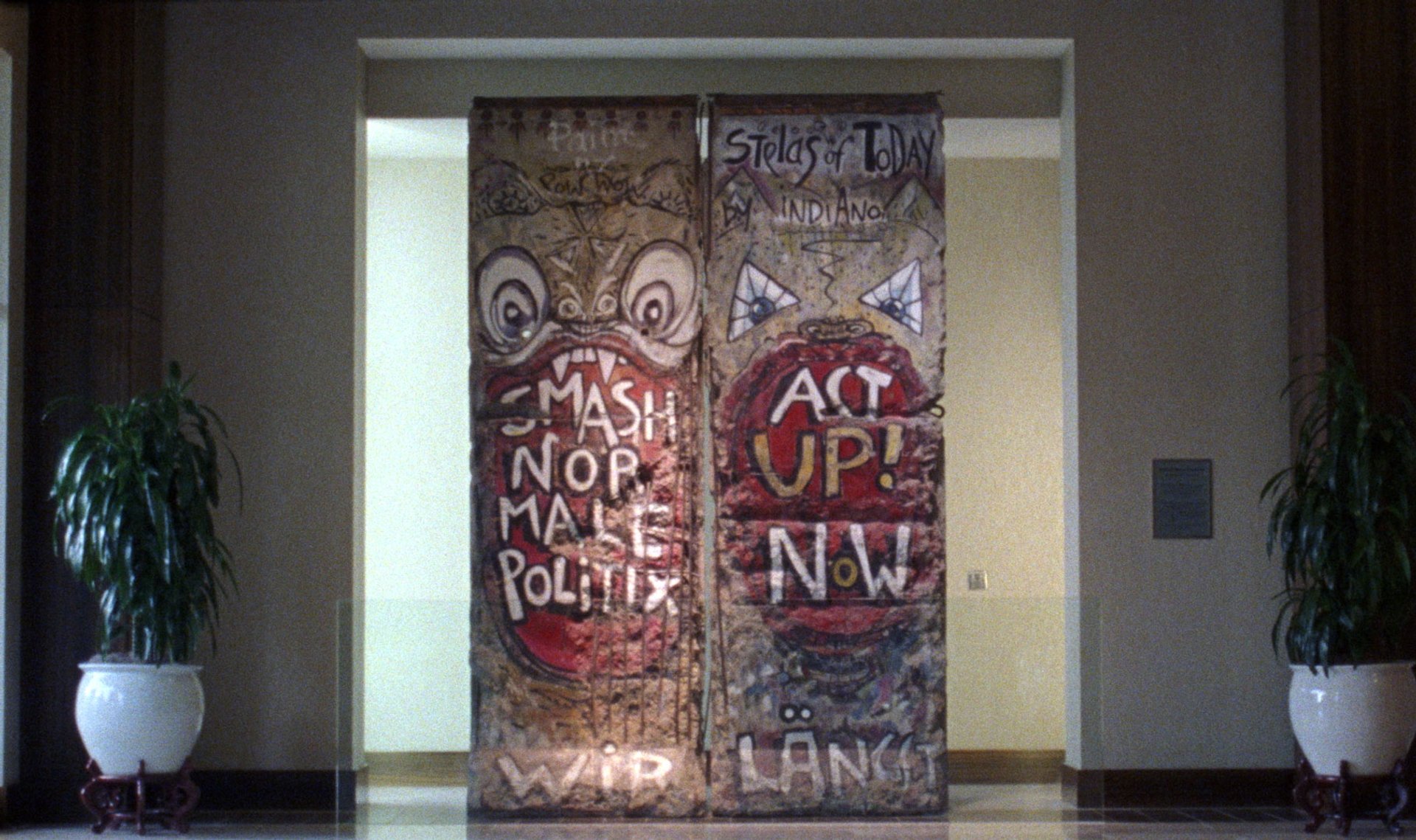

A still from The American Sector, by Courtney Stephens and Pancho Velez

The American Sector, a quirky and improbably cerebral US documentary by Courtney Stephens and Pancho Velez, visits some 75 stelae that were once sections of the Berlin Wall and are now dotted across in the US—from bleak South Dakota to downtown Miami. Collected by American institutions, individuals and businesses, the slabs, each 3.5-meters tall, are viewed in their new environments at a moment when all monuments are coming under scrutiny. These stelae are massive souvenirs as well as witnesses to the end of the Cold War. Each stands today, often by default, as a memorial, but almost no one seems to notice.

At the George H. W. Bush Library at Texas A & M University in College Station, a row of the slabs is breached by a team of giant bronze horses, suggesting the defeat of Communism at a shrine to the man who was in the White House when Germany unified. On a residential street in Los Angeles, a concrete block smeared with graffiti is a trophy acquisition. But why would a slab from the Berlin Wall be in a Las Vegas casino?

The Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan said that an object that outlives its use either passes into extinction or becomes a work of art. Now the stelae, instant art in 1989, are destined to outlast the memory of the events that made them monuments in the first place.