Cubism. Futurism. Constructivism. Dadaism. Surrealism. Amid the maelstrom of artistic “isms” that swirled in the first decades of the 20th century, an obscure Hungarian poet saw a clear and unstoppable logic. Charles Sirató had begun composing “planar” poems in the 1920s that freed words from their lines and gave them pictorial form. As an émigré in Paris, he felt the shock of Modern art: paintings with depth, and sculptures with inner voids and moving, even motorised, elements. In 1936, he wrote a manifesto declaring that all these avant-garde tendencies were offshoots of the same movement: Dimensionism.

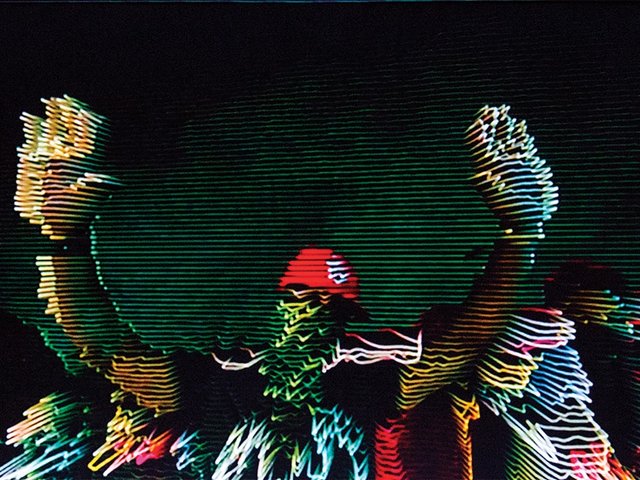

Their emergence after 1905, the year that Albert Einstein published his special theory of relativity, was no accident. “At the origin of Dimensionism are the European spirit’s new conceptions of space-time (promulgated most particularly by Einstein’s theories) and the recent technical givens of our age,” Sirató wrote. He used the formula “N + 1” to express how literature, painting and sculpture had each “absorbed a new dimension” on top of those they already had. So, painting would go from two to three dimensions, while sculpture would now have four. The movement’s endpoint would be “cosmic art”, which would not be passively viewed but experienced with all five senses.

Robert Matta’s Genesis (1942) was another work that responded to advances in science © 2018 ARS, New York/ADAGP, Paris; Photo: Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington

The Dimensionist manifesto was signed by prominent artists in Paris and abroad, including Hans Arp, Wassily Kandinsky, Marcel Duchamp, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Alexander Calder and László Moholy-Nagy. “They all came to it with their own particular interests in the sciences,” says Vanja Malloy, the curator of the first exhibition dedicated to Dimensionism, which opens this month at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) in California and will travel next March to the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College in Massachusetts.

The show, and an accompanying book edited by Malloy (Dimensionism: Modern Art in the Age of Einstein, MIT Press), shed light on a movement that was all but forgotten. Sirató’s ambitious plans for a First International Dimensionist exhibition and a magazine, N + 1, fell by the wayside as he developed a debilitating illness and was forced to move back to Budapest. The Second World War and then the Cold War prevented him from returning to Paris. “For him, it was this great disappointment that [Dimensionism] never happened,” Malloy says.

Yet in the 1960s, Sirató wrote an unpublished history of the movement—now reproduced for the first time in English in the catalogue—observing how its scientific ideas “were still incredibly informative for a range of art through to the 60s and even in the US”, Malloy says.

Isamu Noguchi’s E = mc2 (1944) © 2018 The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York/ARS

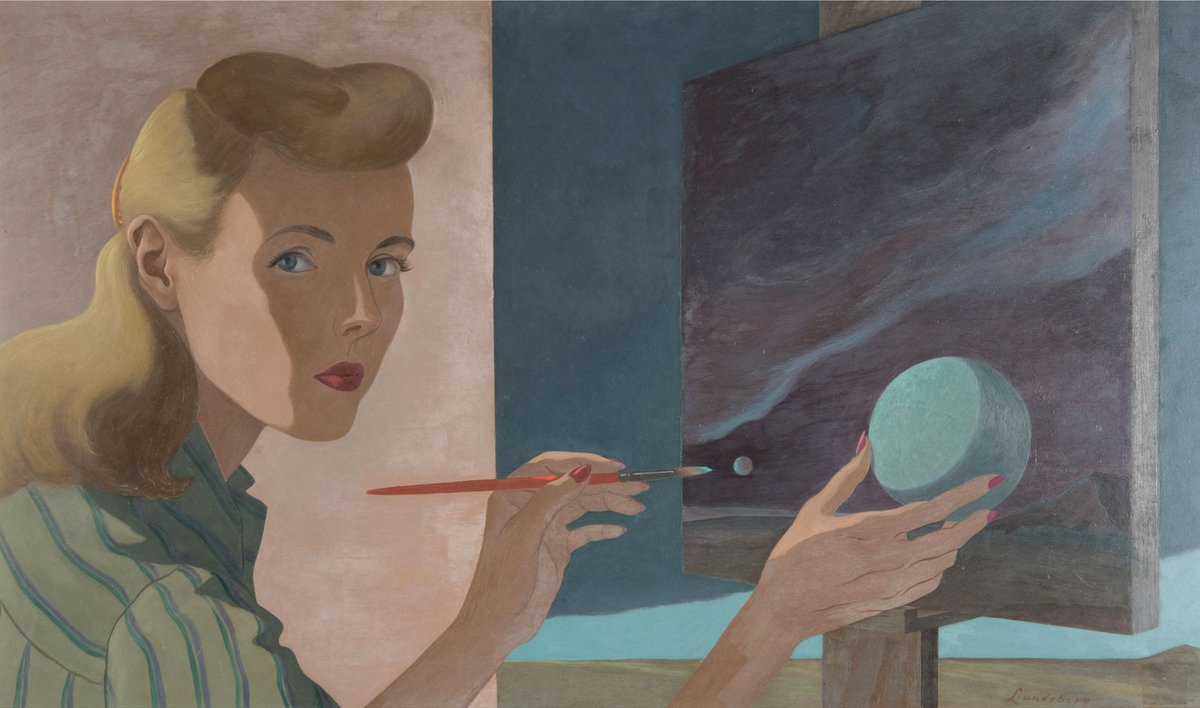

With almost 70 works largely drawn from US collections, the exhibition charts how artists—some affiliated with Dimensionism and others working independently—responded to advances in astrophysics, mathematics, microbiology and quantum mechanics. Included in the show are works by Duchamp and Joseph Cornell that evoke a total solar eclipse, the phenomenon that in 1919 was shown to confirm key elements of Einstein’s theory of relativity. A pair of sculptures by Isamu Noguchi illuminate his deep friendship with the “design scientist” Richard Buckminster Fuller, who explained Einstein’s E = mc² to him. The displays will also show how telescopic and microscopic images available in the mass media filtered through to fine art, as seen, for example, in the work of Helen Lundeberg.

It is important to remember, however, that “these artists were not interested at all in accurately representing or illustrating science”, Malloy says. It was, in fact, a fertile source of inspiration for non-representational art, “an opportunity for them to question everything they had accepted as realities of the universe”.

“Just because you experience space and time one way, it doesn’t mean that’s how it is… so what could it really look like?” she adds. “You can use your imagination.”

The exhibition is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation and the Terra Foundation for American Art, among others.

• Dimensionism: Modern Art in the Age of Einstein, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, University of California, Berkeley, 7 November-3 March 2019; Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, Massachusetts, 28 March-2 June 2019