In the 1920s, she was billed as the “New Woman”: a confident figure with a bobbed haircut and stylish attire striding out into the world to explore life’s possibilities. A global icon known variously as the neue Frau, nouvelle femme, xin nüxing or modan gāru, her image marched across magazine pages, defying traditional assumptions about gender roles and championing an insouciant Modernity. In some countries, that empowered persona stirred indignation or outright resistance.

In a groundbreaking exhibition opening on 2 July at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, that determined woman is equipped with a camera, and blazing a trail that has been grievously overlooked in most accounts of the history of Modern photography. With 185 photographs, photo books, and magazines, The New Woman Behind the Camera charts the work of 120 women from over 20 countries who forged careers as photographers and contributed significantly to advances in the medium from the 1920s to the 1950s. The presentation brims with surprises, inviting viewers to reckon with blind spots in their understanding of that period.

Andrea Nelson, an associate curator in the department of photographs at the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, DC who conceived and organised the exhibition, says the idea for it arose after she was hired in 2010 and was ruminating about generating shows drawn from the NGA’s permanent collection. She was struck by a trove of 90 images by the interwar photographer Ilse Bing that were variously donated by the artist or left by her estate after Bing died in 1998. “She was actually one of the few women photographers that the National Gallery had collected in depth,” Nelson said in an interview. (The show, which was originally scheduled to open first at the NGA last September but was then deferred because of the coronavirus pandemic, travels there this autumn.)

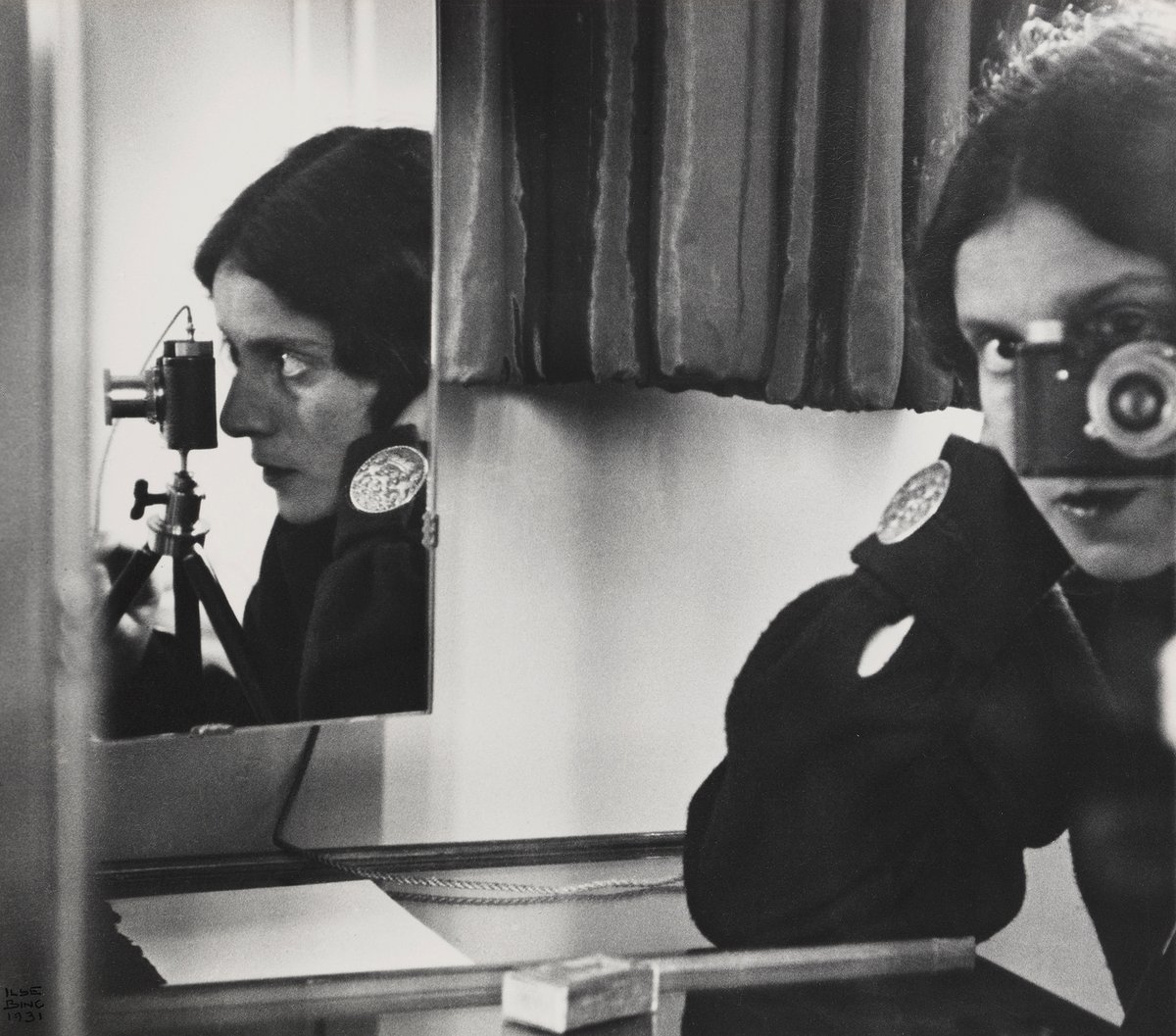

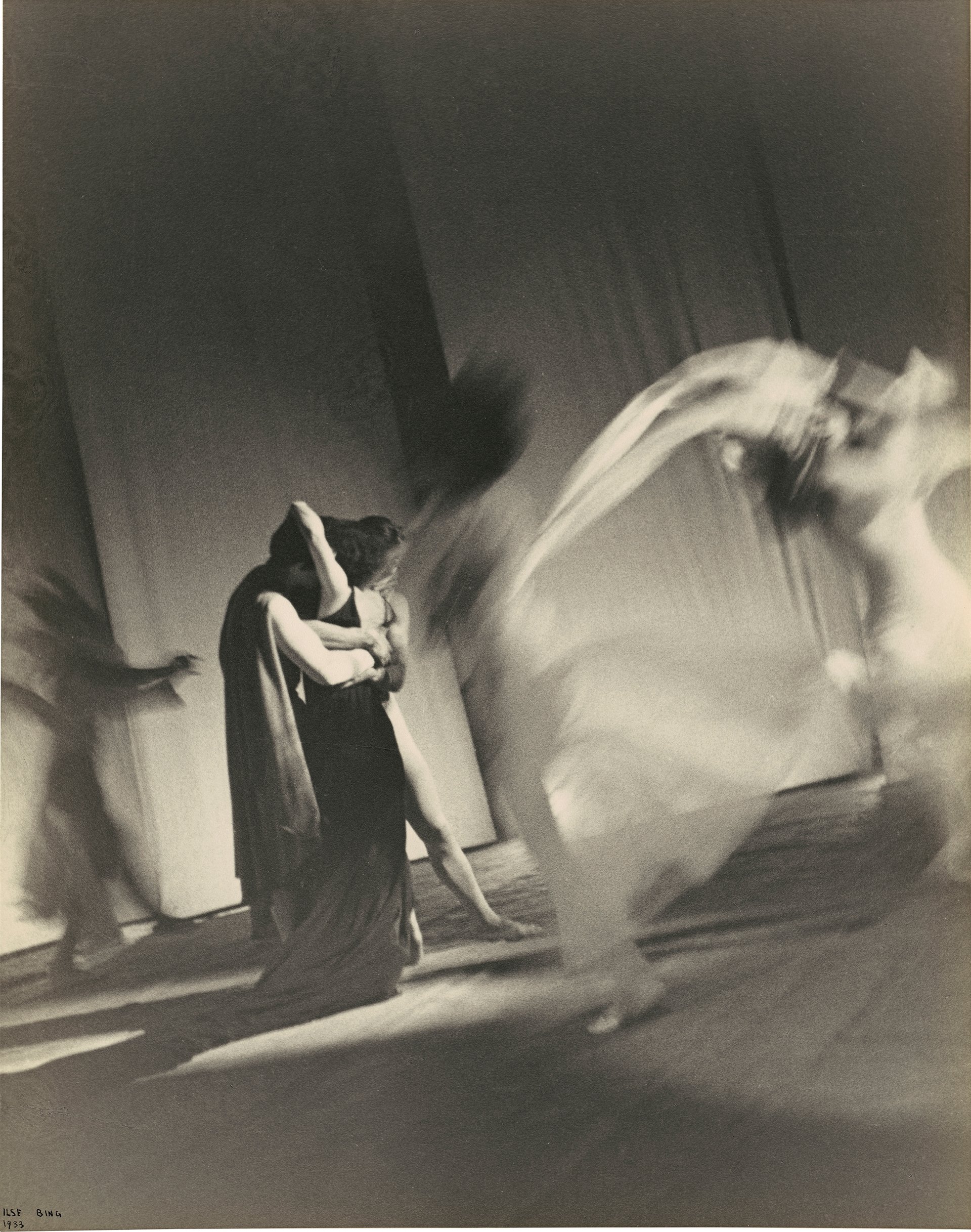

Born into a Jewish family in Frankfurt, Bing became interested in photography while creating architectural illustrations for her art history dissertation there, and eventually gave up her academic studies to pursue a career with the camera. She bought a Leica 35mm model in 1929 and moved the following year to Paris, where she met leading lights in avant-garde photography including Brassaï and André Kertész. Bing began experimenting compositionally and with light effects in self-portraits, images of Parisian streets and photographs of quotidian objects, followed by a striking series of pictures of dancers at the Moulin Rouge and other performers as well as commercial and fashion work in the burgeoning German and French magazine industry.

Ilse Bing Ballet "L’Errante", Paris, 1933 National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

Known to the cognoscenti as “the Queen of the Leica”, she became a firmament in the constellation of Modernist photographers, included in important exhibitions in Paris and New York. Then the Second World War intervened, and Bing and her husband were both interned with other Jews in the south of France before fleeing to New York in 1941. Her photographic career gradually diminished after that, and she gave it up altogether in 1959.

Yet what she achieved from 1930 to 1940 remains a wonder to behold. “To me, she represents the established narrative of the interwar photographer,” says Nelson. “And as I began to dive deeper, I started to think about this larger community of women photographers who were entering the field, particularly in Germany and France. Did they have the same experiences as Bing, different experiences? But then I just started asking, wait a minute, was that true elsewhere [in the world]? What I really wanted to do was hopefully move beyond the Euro-American narrative that has really structured the history of photography.”

“I just felt that there wasn’t a look at the greater diversity of practitioners during the Modern period. So I took off down that road.”

The exhibition is inflected not only by each woman’s unique story but by the social, political and economic tumult that framed much of their work, including the Great Depression, two world wars and the rise of Communism and Fascism. While most histories of photography’s Modern period centre on 1918 to 1945, Nelson expanded her research to absorb all of the 1940s and 1950s after she grasped that women were involved in photographing events surrounding the advent of India’s independence in 1947, the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and the postwar US occupation of Japan from 1945 to 1952.

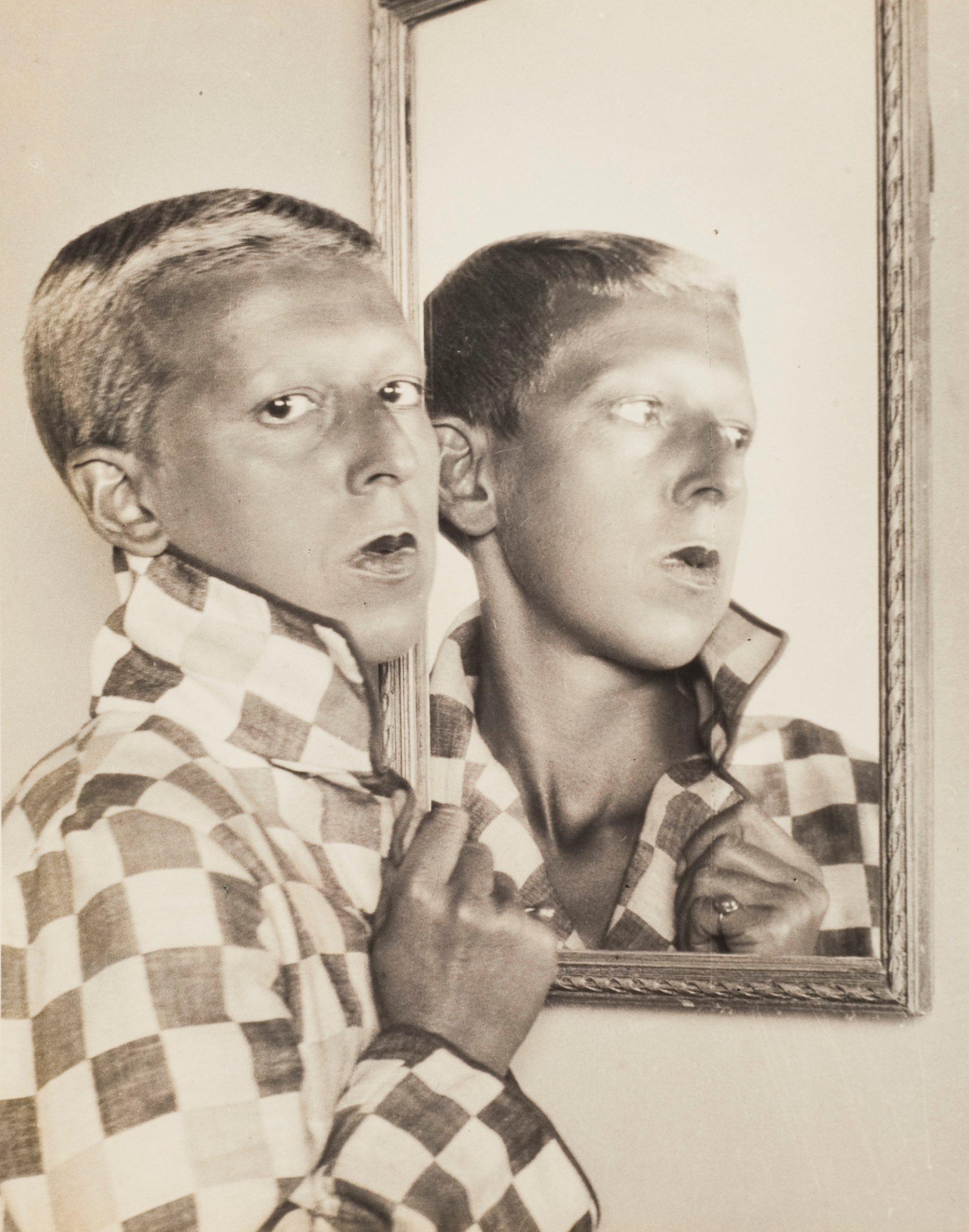

Of the nine sections featured in the Met’s presentation, organised by Mia Fineman, curator in the museum’s department of photographs, with help from the research assistant Virginia McBride, the first is “The New Woman”, an array of portraits of the photographers that were shot by themselves and others. In some cases, the women embrace avant-garde techniques such as mirroring, double exposures or photomontage, Fineman notes.

Claude Cahun, the Surrealist and ultimate self-portraitist, casts a quizzical gaze while mirrored and telegraphing her customary refusal of gender definitions; Ré Soupault, the Bauhaus photographer who later worked in Paris, Tunisia and New York, merges her image with that of a newspaper in a dreamlike double exposure. Homai Vyarawalla, an Indian photojournalist who is one of the show’s more intriguing discoveries, stands in the sea off a beach in Mumbai with the water stretching up to the hemline of her dress while fixing her sights on an unknown subject.

Claude Cahun, Self-Portrait (around 1927) Wilson Centre for Photography

Nelson points out that while the exhibition’s through line is the New Woman, a symbol of emancipation that took hold in the 1920s, the idea is hard to pin down from one region to another and changes over time. Coined in 1894 in Britain, the moniker later gained currency in the US and became associated with suffrage movements. Still, many of the women highlighted in the exhibition might not consider themselves feminists or New Women, Nelson notes.

“My sense is that I’m sure that a number of these women photographers would not agree to that,” she says. Fineman agrees: “Many artists bristle at that kind of thing.” In fact, Fineman noted at this morning's press preview of the exhibition that many of the artists featured in the show would have been insulted to be categorised as "women photographers".

Yet the trope of the New Woman seems to sum up the common motivations of many of these female practitioners, who chafed at restraints on their freedom and found the camera to be a tool for empowerment. “The fight for having the ability to make life choices, from whether or not you want to work outside the home, whether or not you want to marry, whether or not you want to have children, to be more politically active—I think the New Woman is a symbol of that,” Nelson says.

In some countries, such as China, fledgling photographers personifying the New Woman met with resentment or resistance, Nelson says, especially because the powerful photograph, Hollywood advertising, bobbed hair styles and Modern dress were so heavily associated with Western conventions. Beyond gender bias, “what they were facing outside of Western Europe and the United States was this additional level of being accused of going against their nationality, of not supporting their culture,” the NGA curator says.

The exhibition, which is accompanied by a catalogue, also emphasises the role of the portrait studio in training enterprising women to take up the camera. Many began as refinishers or retouchers and then rose in the profession, becoming full-fledged photographers and even establishing their own studios. Dorothy Wilding, who built a successful career in retouching in London—“you had to make your clients look amazing,” Nelson notes—opened a studio in London in 1921.

Wilding is represented in the show by a 1937 portrait of the British actress Diana Wynyard with an Art Deco aesthetic, and Nelson observes that the photographer also established a relationship with the royal family and shot the coronation and accession of Queen Elizabeth II. “Her portraits of the new queen were sent to embassies around the world while also becoming the basis for stamps,” the curator says.

(Nelson adds that she was chagrined to witness scenes in the Netflix series “The Crown” in which only male photographers shot the queen: “I just thought, the writers and directors missed a really good opportunity,” she says.)

The introduction of lightweight cameras in the late 1920s enabled women to exit the studio and capture street scenes in a critical avenue to their development, the exhibition shows. In a section called “The City”, the Met presents examples such as Vyarawalla, who moved with her husband to New Delhi in 1942 to join the British Information Services. She chronicled the final days of the British Empire and the arrival of Indian independence, photographing figures such as Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi.

Yet both Nelson and Fineman point to a far different favourite: Vyarawalla‘s distinctive photograph of Mumbai’s bustling Victoria Terminus railway station, shot in the early 1940s. The station, completed in 1887, is now a World Heritage site, a “really spectacular work of British colonial architecture,” Nelson notes. Playing with Modernist strategies, Vyarawalla brings her camera low to the ground and glimpses the train station through the wheels of a rickshaw in a “conscious exploration of perspective” that defies tradition, the curator says. The photographer is also represented in the show in images of Mumbai art school students and an Allied victory parade in which tanks rumble through the streets of New Delhi.

Homai Vyarawalla, The Victoria Terminus, Bombay (early 1940s) Homai Vyarawalla Archive/Alkazi Collection of Photography

Viewers can home in as well on photographs such as Genevieve Naylor’s early 1940s image of a trolley in Brazil, with passengers outside the tram risking their lives to hold on, or Tsuneko Sasamoto’s Tokyo scene from 1946 reflecting the heavy imprint of the American military occupation by depicting a post exchange that provided goods to US troops. The inclusion of the modern woman striding past the store highlights the growing popularity of Western fashions in Japan after the austerity of the war period. (As part of her research, Nelson travelled to Japan to interview Sasamoto, who is now 106, in an assisted-living facility.)

Genevieve Naylor, São Januário Trolley (early 1940s) National Gallery of Art, Washington

Tsuneko Sasamoto, Ginza 4 Chome PX, 1946 (printed 1993 Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

Sections devoted to social documentary and reportage attest to the role of women photographers in recording critical events, from the global depression to the civil war in Spain to the Second World War. Dorothea Lange, who stepped out of her studio after the stock market crash to work for the US Farm Security Administration and document rural poverty in the 1930s, is represented by three images. Among them are a 1936 portrait of glum Oklahoma drought refugees by a California roadside and a poignant 1942 shot of a store in Oakland, California, that had been owned by a Japanese-American before he was interned as part of a federal wartime policy targeting people of Japanese descent. A sign outside the store pleads, "I am an American."

Outside the studio, Lange stuck to her large-format camera, Nelson, says, unlike the many others who adopted lightweight models: “She never tried to hide her camera and she wanted her subjects to know what she was doing.”

Dorothea Lange, Drought refugees from Oklahoma camping by the roadside, Blythe, California, August 17, 1936 National Gallery of Art, Washington

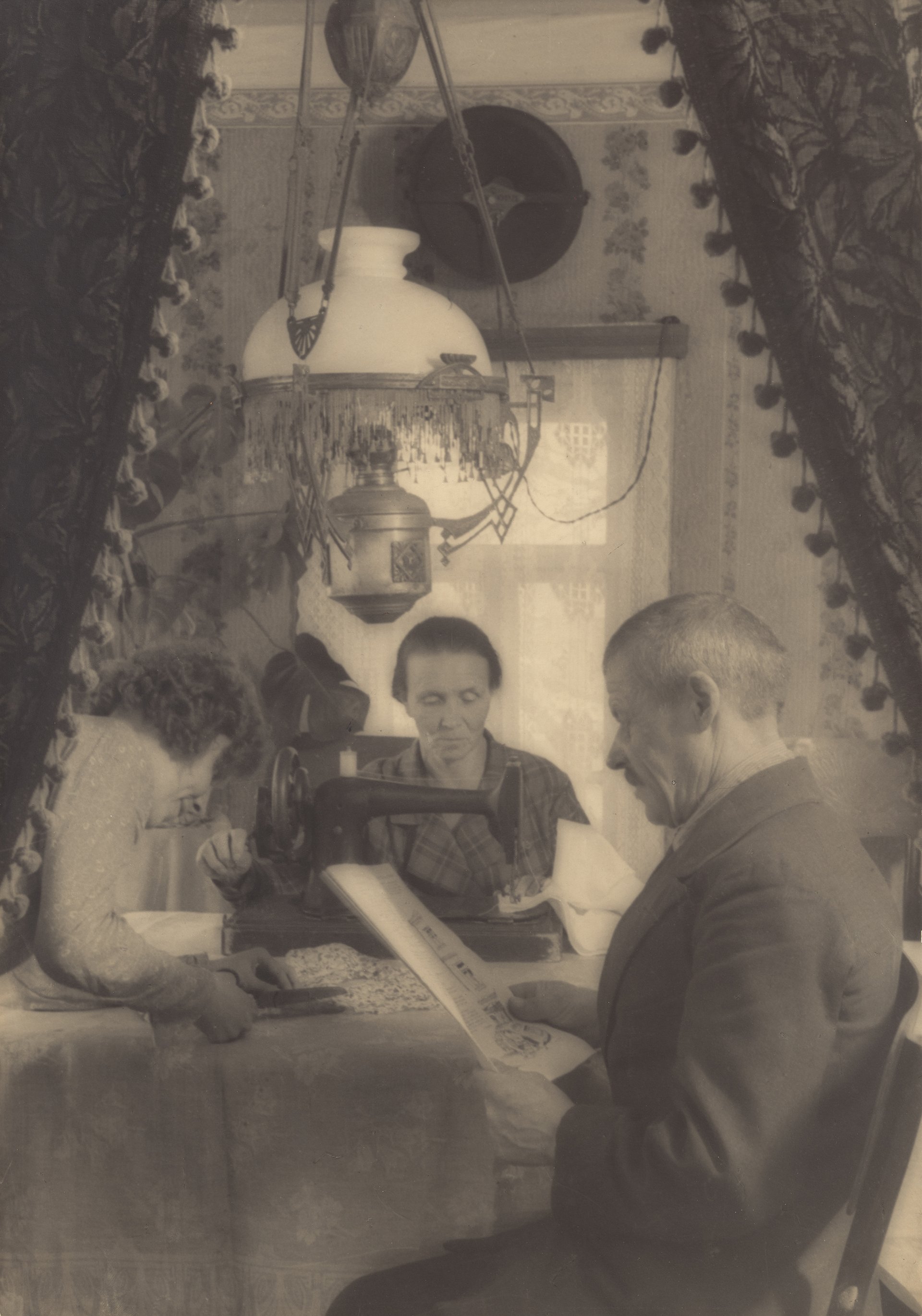

In the Soviet Union, Elizaveta Ignatovich was meanwhile grappling with official requirements for a heroic Socialist Realist style, photographing a family in a 1930s farm collective in a gauzy soft-focus light while accentuating the narrow framing of a curtain as well as geometric elements like an overhead lamp. Earlier Ignatovich had favoured more dynamic compositions, but “there was this very aggressive push to end avant-garde practices," Nelson says.

Elizaveta Ignatovich, Family of a Kolkhoz Farmer (1930s) National Gallery of Art, Washington

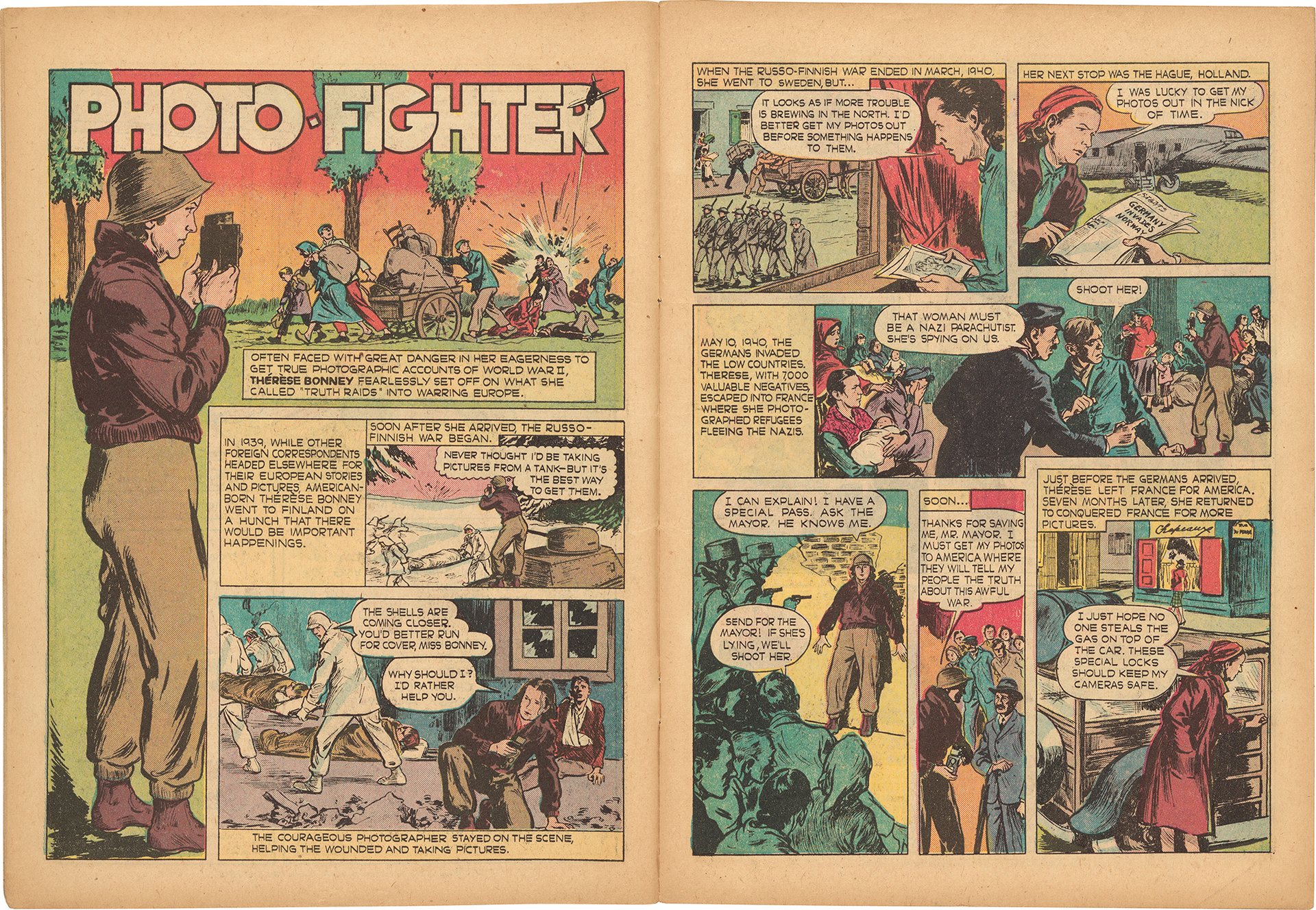

The exhibition highlights photographs by intrepid photographers such as Thérèse Bonney, an American who captured men sifting through rubble after a 1940s bombing in London as well as wounded Russian prisoners being returned from the front after the Soviet offensive against Finland in 1939. Bonney is also represented by a book, Europe’s Children, with photographs of children who were driven from their homes in wartime, lived in camps and then returned amid deep trauma, Fineman notes. And a comic book celebrates how Bonney was memorialised in the heroic role of the “Photo Fighter.”

Artist: Thérèse Bonney, Photo Fighter, in True Comics (July 1944) National Gallery of Art Library

In a 1944 image, the British photographer Constance Stuart Larrabee witnesses the public shaming of a French woman in Saint-Tropez who was found to have consorted with occupying German officers and is paraded through the streets, her head shorn; the American Margaret Bourke-White gets star treatment for her forays with the US Air Force in a 1943 Life magazine spread headlined, "Life's Bourke-White Goes Bombing".

In an “ethnographic approaches” section, the show whiffs out the dogged research by figures such as the French artist Denise Bellon, who evocatively photographed a woman with a fan-shaped hair style in Guinea, and the Swiss photographer Ella Maillart, who travelled through the Gobi desert, Turkey, Iran and Afghanistan and depicted women in Samarkand (now in Uzbekistan) who were visiting a street photographer. The anthropologist and civil rights activist Eslanda Goode Robeson, wife of the singer and rights campaigner Paul Robeson, portrays a Ugandan miner in Kampala having his hair wrapped in accord with local traditions.

Fineman suggests that Goode Robeson's point of view differed from that of white ethnographers. In an illustrated 1945 book about her travels and fieldwork, Goode Robeson drew parallels between the colonialist legacy in South and East Africa and racist oppression in the American South, an exhibition label notes, while observing “a growing spirit of resistance” in some African countries.

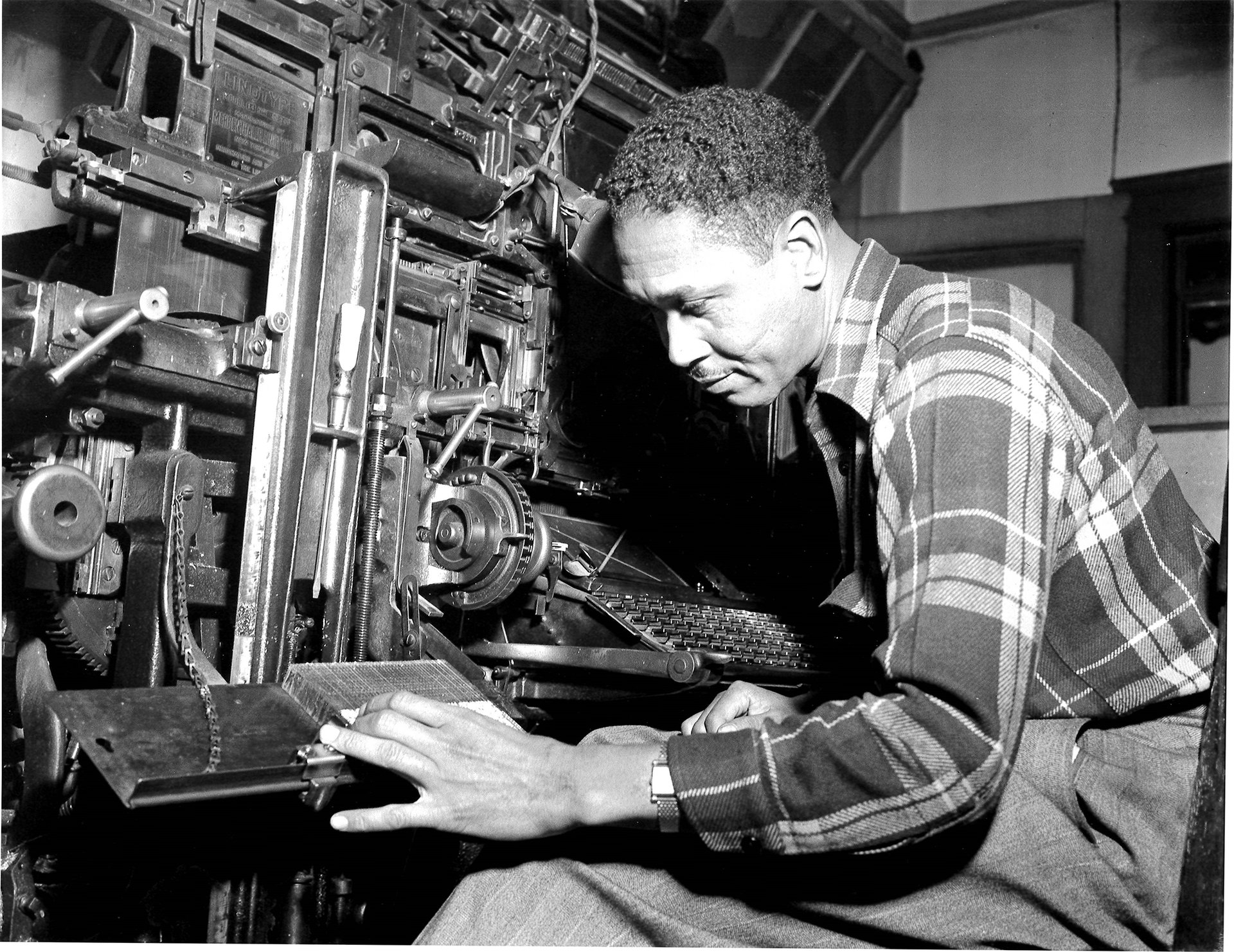

Other African-American artists are celebrated in the show as well, including Vera Jackson, who became a staff photographer for a Black-owned newspaper in Los Angeles, The California Eagle, and covered civil rights protests as well as taking pictures of celebrities such as Jackie Robinson and Lena Horne. A 1940s image of a man toiling on a printing press highlights the importance of Black-owned media for African-American communities across the US in that period, Nelson says.

Vera Jackson, Man at Printing Press (1940s) Collection of Friends, Foundation of the California African American Museum, Gift of the artist, Courtesy of the California African American Museum

The Black artist Florestine Perrault Collins, who toiled as a cleaner in a dental office in New Orleans, found liberation by working in a photography studio from 1920 to 1949, photographing local African-Americans. That allowed her to “forge an identity outside the limitations of racism and gender discrimination”, Nelson says. In a self-portrait taken to advertise her photographic services, Collins presents herself in a stunning dress with a jewelled clip in her hair–“I think very much in the form of a New Woman.” the curator notes.

Fineman says that Collins's work was rediscovered and then painstakingly reassembled by a grand-niece who combed through flea markets.

Florestine Perrault Collins (1920s) Collection of Dr. Arthé A. Anthony

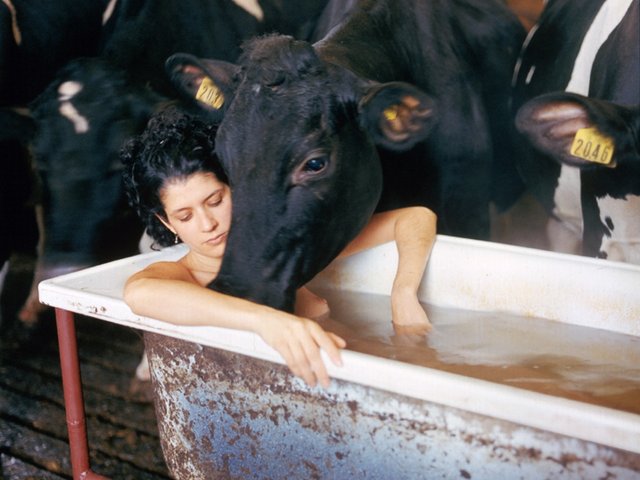

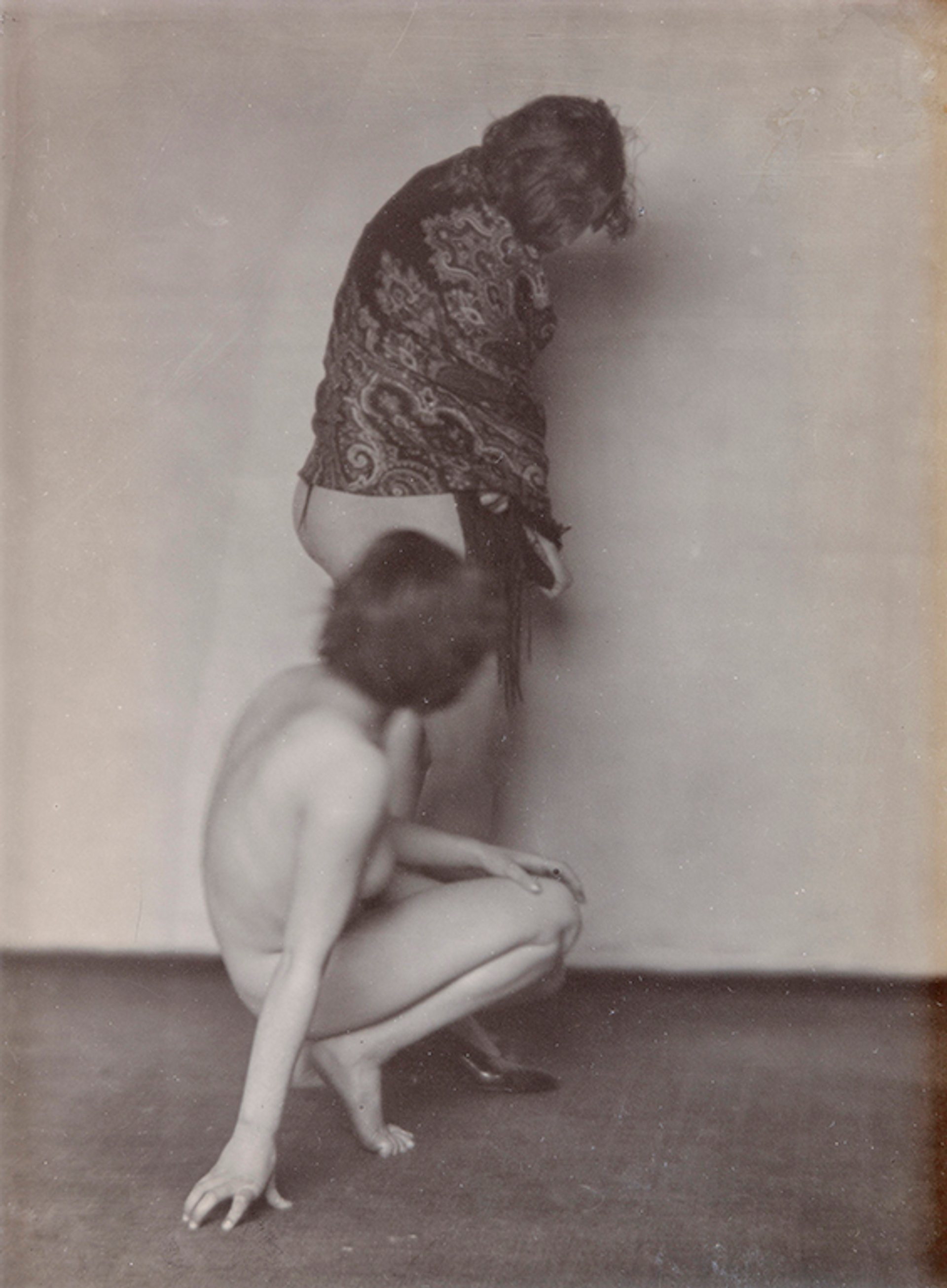

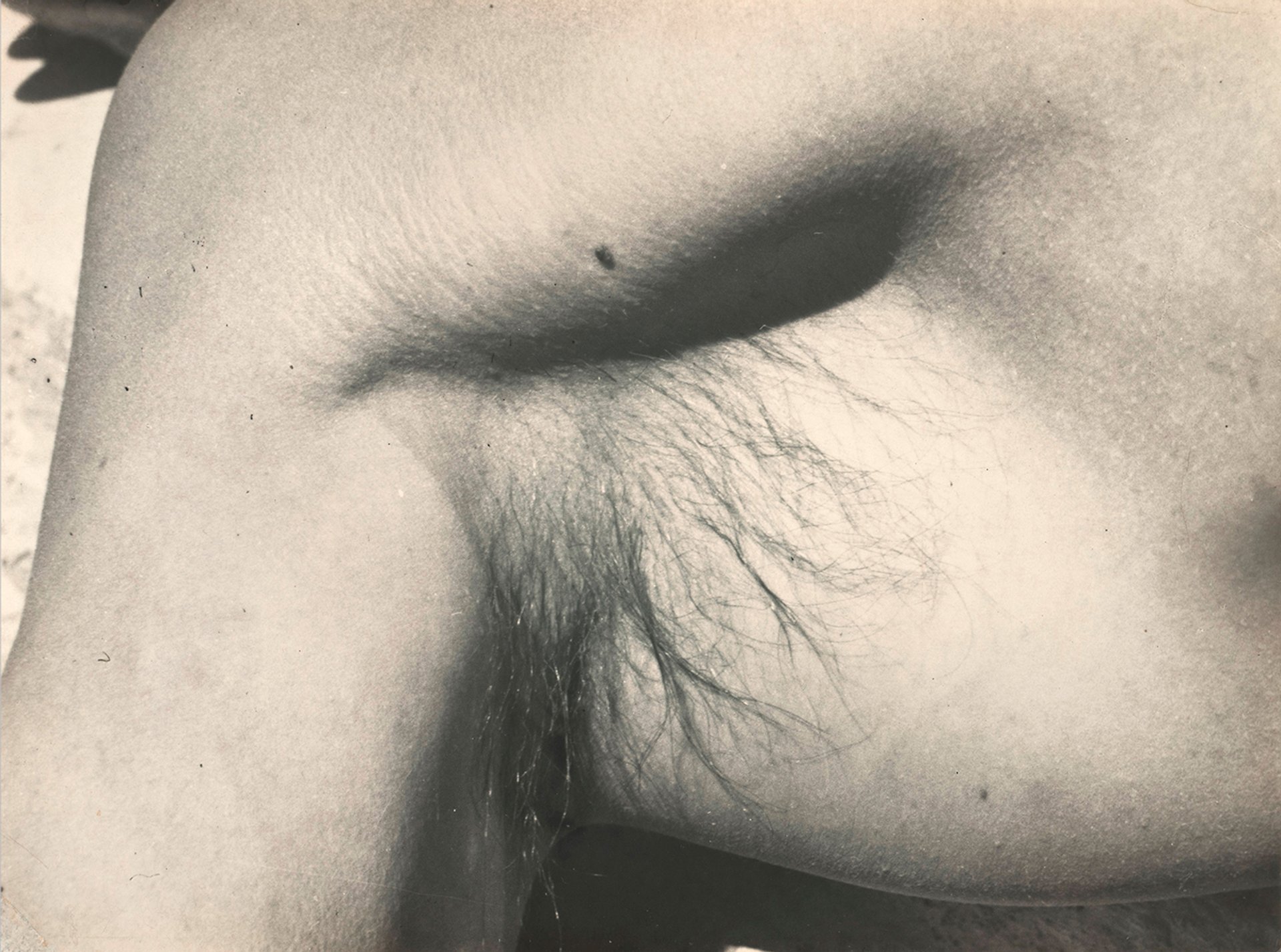

A section exploring “modern bodies” delves into changing ideas about health and sexuality by focusing on nudes, dance and athletes in action. Sometimes the “female gaze” of a woman photographer cannot necessarily be distinguished from that of a male contemporary. But there are compelling standouts: the German photographer Germaine Krull, for example, depicts women interacting in sexual or more ambiguous ways, thereby “frustrating the conventions of pornographic photography”, Nelson notes.

Germaine Krull, Study for The Nude, 1924 Collection of Trish and Jan de Bont

Ilse Salberg, an art teacher and gallery owner in Cologne who fled the Nazis and settled in Paris, is represented by a 1938 close-up of an armpit, one of eight photographs focusing on body parts of her romantic partner, Anton Räderscheit. “It almost looks like a landscape,” Nelson says. “You can't quite tell what you’re looking at, so it's making the body both familiar and strange.” In an innovative 1928 nude self-portrait by Jeanne Mandello, a German Jew living in exile in Uruguay, the artist poses next to fronds that cast stippled shadows across her body.

Ilse Salberg, Anton in Detail (1938 ) Galerie Berinson, Berlin

The exhibition also chronicles the rise of the fashion industry beginning in the 1920s, which opened career opportunities for female journalists, models and photographers. As photographs supplanted drawings in fashion spreads and advertising, women found the liberty to express themselves with the camera, sometimes setting up their own studios in the US, France and Germany. Fashion plates enshrined the ideal of the New Woman and also encouraged a largely female readership to vaunt their tastes and ambitions.

Yva, Fashion Photograph from around 1930 National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection

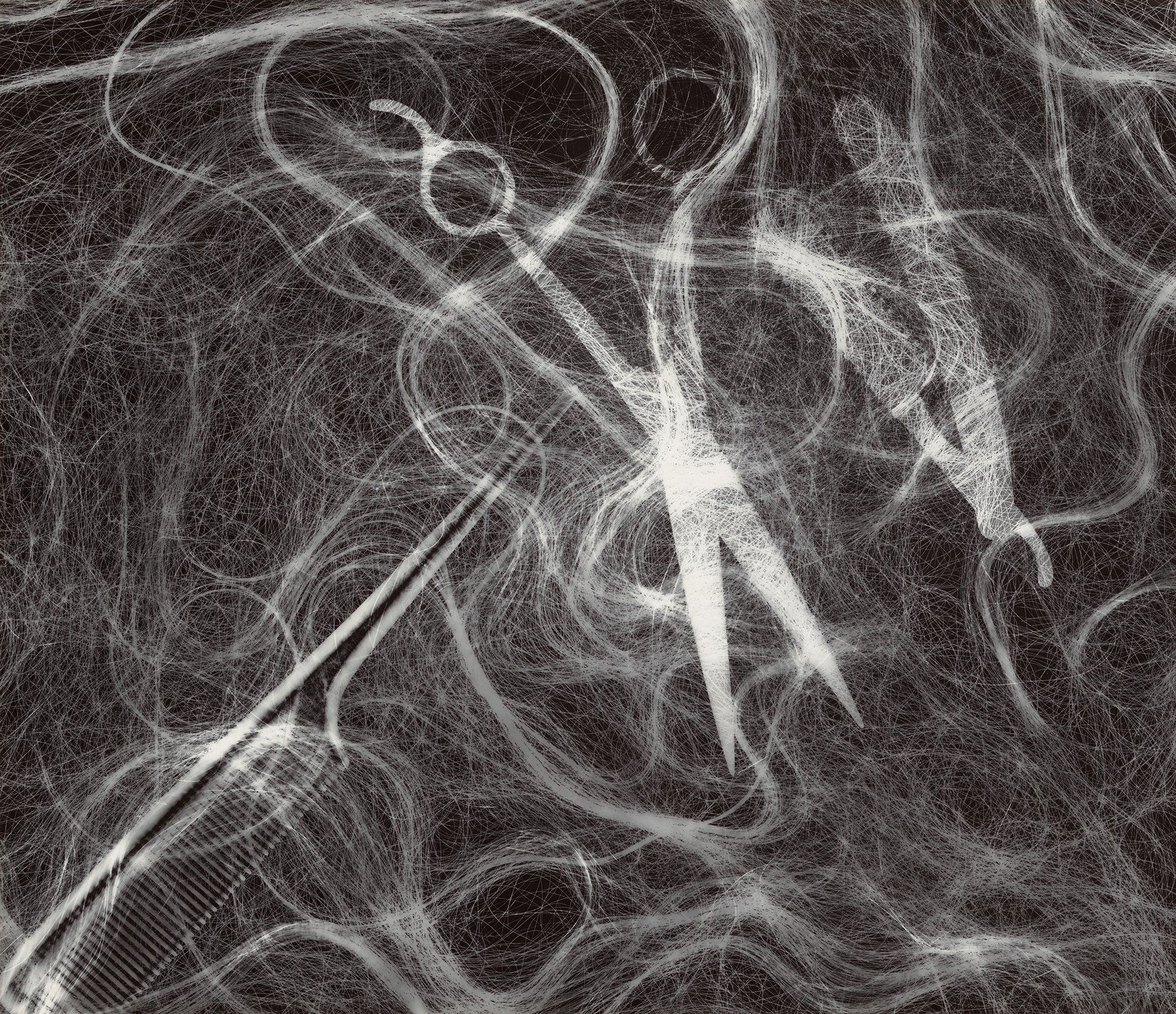

A gallery focusing on avant-garde experimentation showcases women who harnessed techniques like multiple exposures, photomontage or the photogram, an image made without a camera or a negative by placing objects onto the surface of a light-sensitive material. Bernice Kolko’s phantasmagorical photograph from around 1944 layers strands of hair with scissors, a comb and a razor blade, suggesting a visit to a barber or beauty salon. For Nelson, it evokes “that very symbolic act of cutting your hair short that many women did to have greater agency”.

Bernice Kolko, Photogram (around 1944) National Gallery of Art, Washington

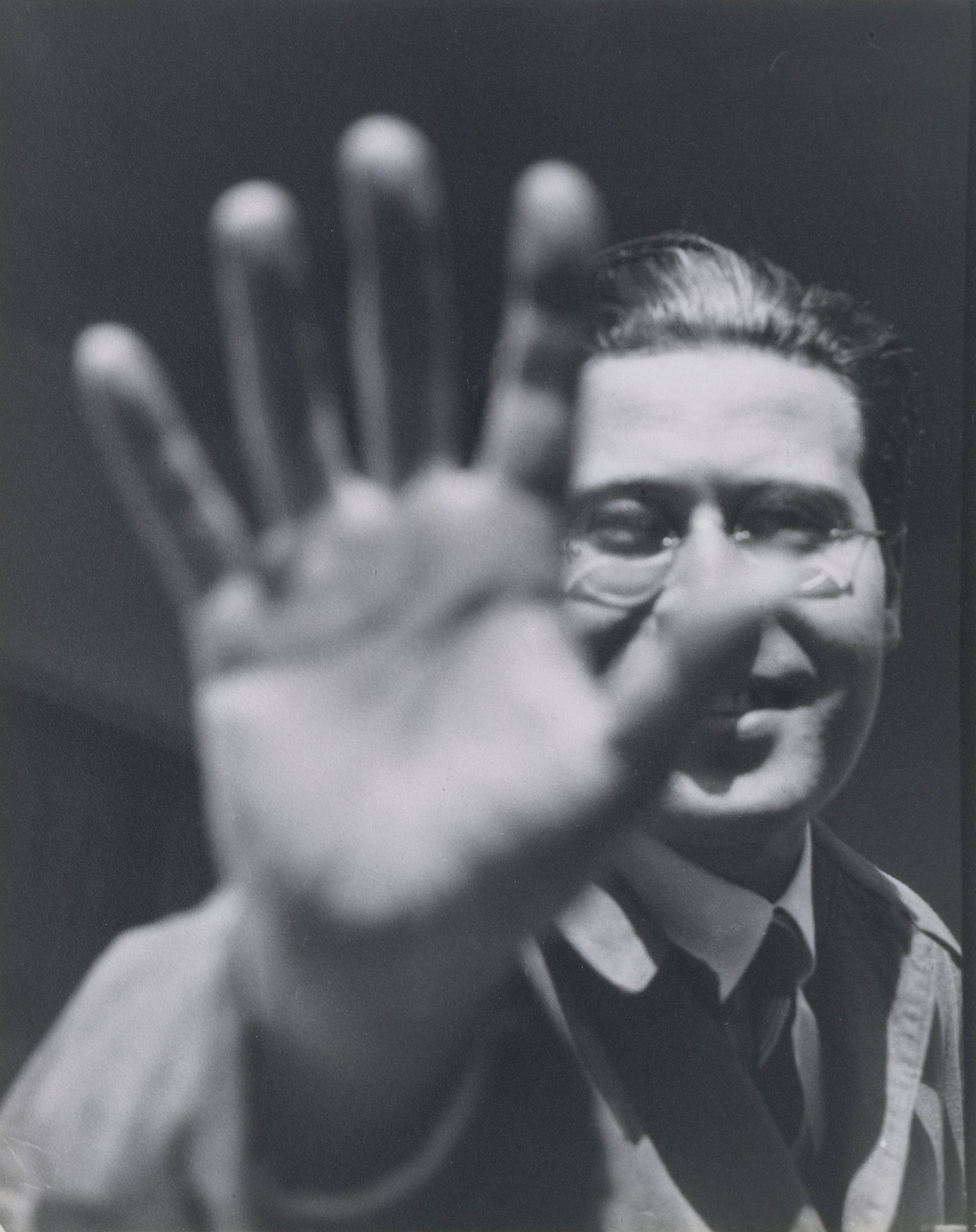

Lucia Moholy’s 1925-26 image of her celebrated photographer husband, László Moholy-Nagy, extending his hand in front of the camera was long assumed to be his own self-portrait, but research has led scholars to conclude that his wife shot the image. A wall label calls it “a striking example of the tendency to attribute the work of women artists to their male partners”.

Lucia Moholy, László Moholy-Nagy (1925–26) Ford Motor Company Collection

In many cases, photographs by the women artists in this section—indeed, in the exhibition as a whole—have been judged to be derivative, influenced by the style of a lionised male artist. That is a received wisdom that Nelson hopes to correct. “What I often hear is, ‘Oh, this practitioner was just really influenced by one of the great male photographers,” she says, “as if they didn’t have their own sense of originality.”

Yet in some regions of the world, gender ironically offered female photographers special entrée: demand for their services arose because social and religious traditions restricted women from interacting with men outside their own families. Because of her gender, Soupault gained access to a "forbidden" quarter for women without education or family support in Tunisia, some of whom turned to prostitution, and photographed a woman on the street inspecting her image in a hand mirror. And Karimeh Abbud was able to shoot portraits in private homes in Palestine, often while bringing along her own backdrop as reflected in a 1930s photograph of three women.

In Palestine, female photographers overwhelmingly worked for studios owned by men, and their finished photographs did not identify them as artists. But Abbud was an exception: in the early 1920s she set up her own studio, Nelson says, stamping her work with the label “Karimeh Abbud Lady Photographer” in Arabic and English. (Abbud also produced postcards of sites in the Holy Land.)

Karimeh Abbud, Three Women (1930s) Issam Nassar

For both Nelson and Fineman, the most striking insight they gained in preparing the show is how many of these photographers have been erased from art historical chronicles or left out of museum collections—even though some were once featured in major exhibitions or had their work published in a multitude of magazines. “Many of these people I had never heard of, and I’m an art historian specialising in photography," Fineman points out. “It was the male photographers who were canonised while the women were largely forgotten—even women who were super-famous in their own lifetime.”

“They dropped out of history,” says Nelson. “To understand all the different ways this happens has been very eye-opening to me.”

Since most of the artists in the show are represented by just one or two photographs, the path to further research is wide open, she adds. “It’s for future scholars to just dig into, to flesh out these stories and present deeper investigations.”

• The New Woman Behind the Camera, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2 July–3 October; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 31 October–30 January 2022