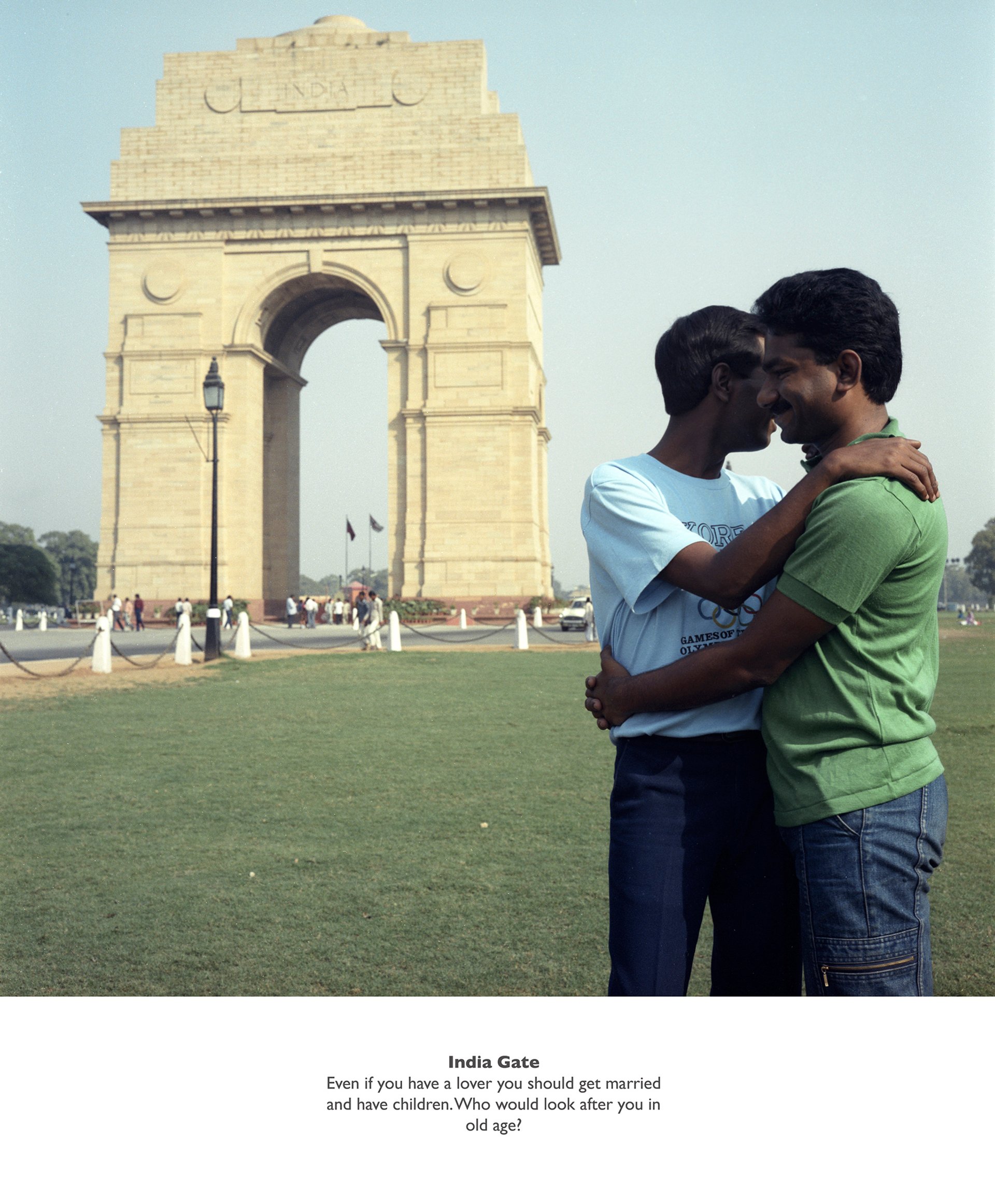

When the photographer Sunil Gupta exhibited his Exiles series—depicting the hidden lives of gay men in Delhi—in a group show at the Photographers' Gallery in 1987, the works “sank without a trace”, he says. “Too foreign, too ethnic. It was unintelligible. People didn’t know what to do with it.”

Twenty-three years later, in the same London venue, the series is once again on show for From Here to Eternity, Gupta’s first major career survey, which uses 16 distinct bodies of work to chart his five-decade-long career and tell the probing, personal narrative of a gay Indian immigrant in the West.

“I seem to be having a moment,” says Gupta, who recently featured in the Barbican’s Masculinities group show and will receive a retrospective at Toronto’s Ryerson Image Centre in 2021. In the past two years Tate and the Museum of Modern Art in New York have both acquired works from Exiles.

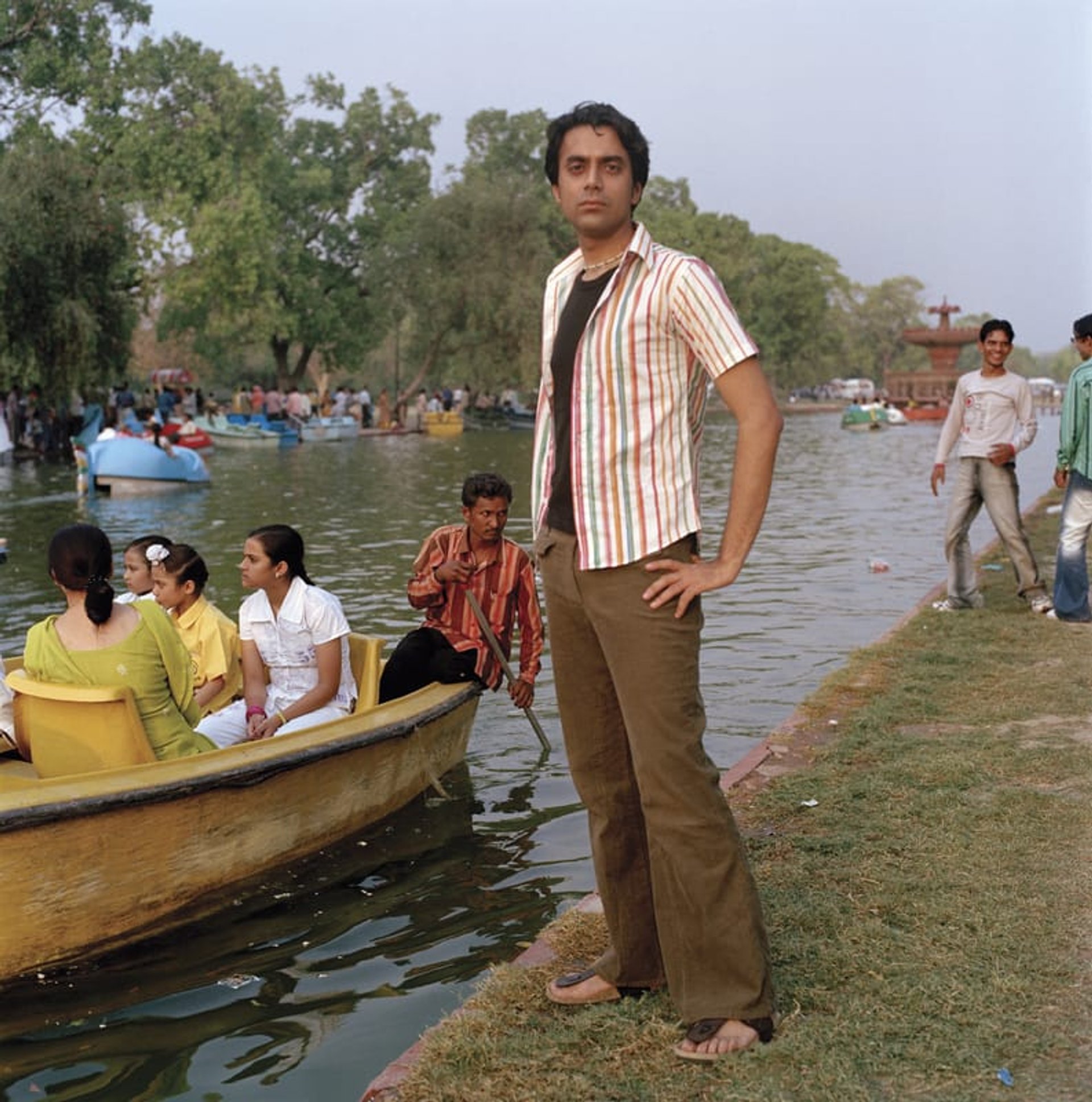

India Gate. 1987. From the series Exiles Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, Stephen Bulger Gallery and Vadehra Art Gallery © Sunil Gupta, all rights reserved, DACS 2020.

Institutional recognition of the 67-years-old's work is long overdue, though the wait is hardly surprising. Left out of traditional British photography's stiflingly white canon, Gupta is also notably market-averse. He explicitly rejected gallery representation until his 50s, having instead largely relied on funding from non-profits such as Arts Council England, as well as from photojournalism assignments.

Yet Gupta's career has also benefitted from being in the right place at the right time. Born in Delhi, he relocated with his family to spend his late teenage years in Montreal, before moving to New York in the 1970s and then to London in the 1980s (both moves were made to follow a love interest, he says). In the process, Gupta has chronicled some of recent history's most vibrant periods of gay life and liberation.

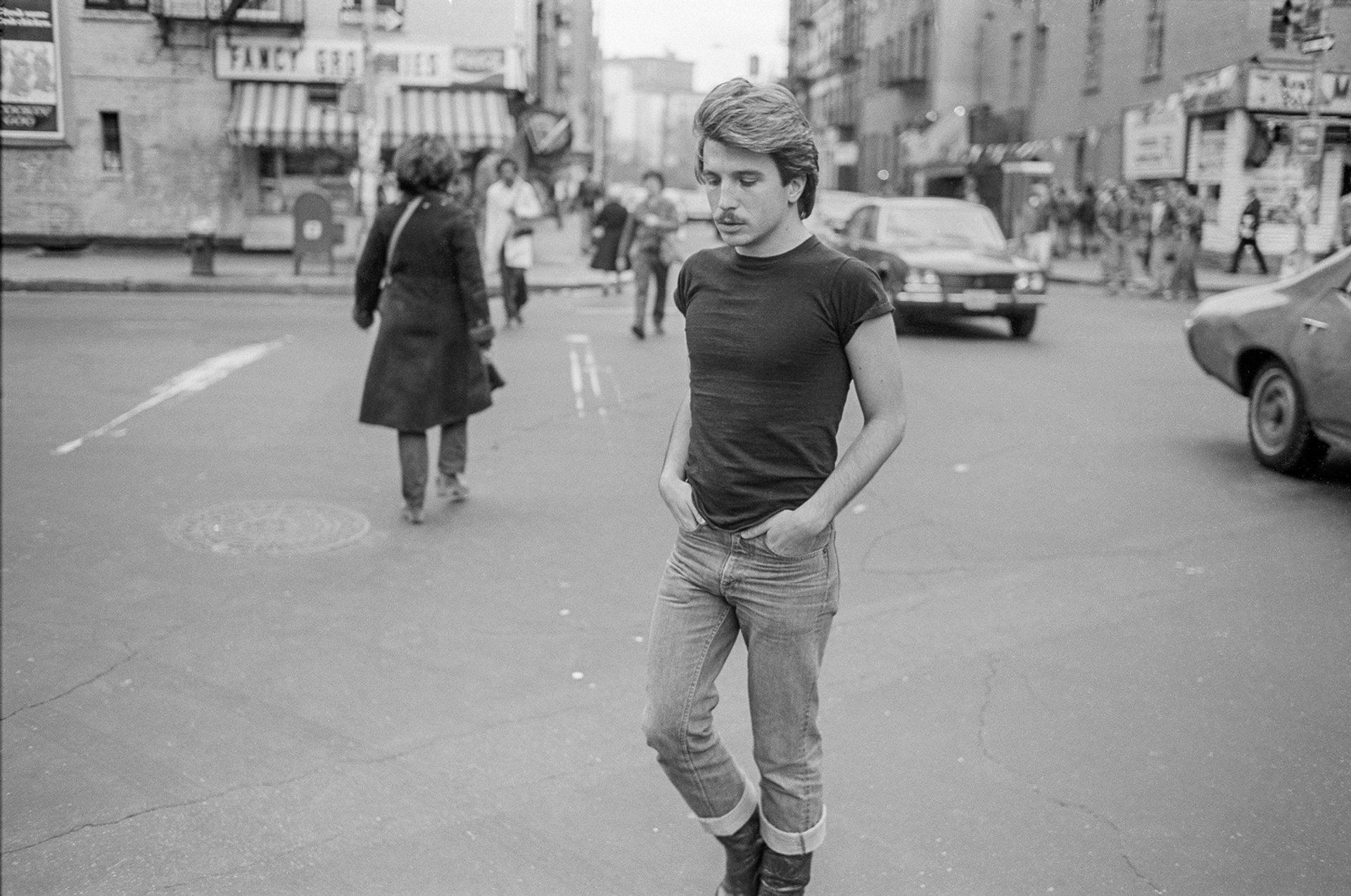

Untitled #22, 1976, from Christopher Street Photograph: Hales Gallery/Stephen Bulger Gallery/Vadehra Art Gallery/Sunil Gupta/all rights reserved, DACS 2020

Among these is one of Gupta’s most famous series, Christopher Street (1976), now exhibited in its entirety for the first time in the UK. Showing black-and-white images of men cruising on Manhattan street corners, they are early forays into a Modernist flâneur-like documentation style. “Sort of Garry Winogrand meets the cruising playground of pre-Aids New York,” he says.

And while street documentary has remained a cornerstone of his practice, Gupta’s broad oeuvre spans a remarkable, perhaps even diffuse, range of styles. "I've more or less done what I wanted my whole life," Gupta says in an interview on show at the Photographers' Gallery. Having not been bound by the gallery system's whims for much of his career, this exhibition reflects the work of an artist concerned less with consciously honing a studio practice than with living a life. If cohesion should be found in the works, it is not in their technical aspects, but rather their vivid sense of activism— one that is rooted in radical, emancipatory gay politics.

"There is something more depressing about today's return to rampant sexuality. This time the politics are less clear"Sunil Gupta

It was when Gupta moved to London—which he now calls home—that he became involved with political movements centred around the capital's South Asian and Black communities and began to document post-colonial struggle in the UK.

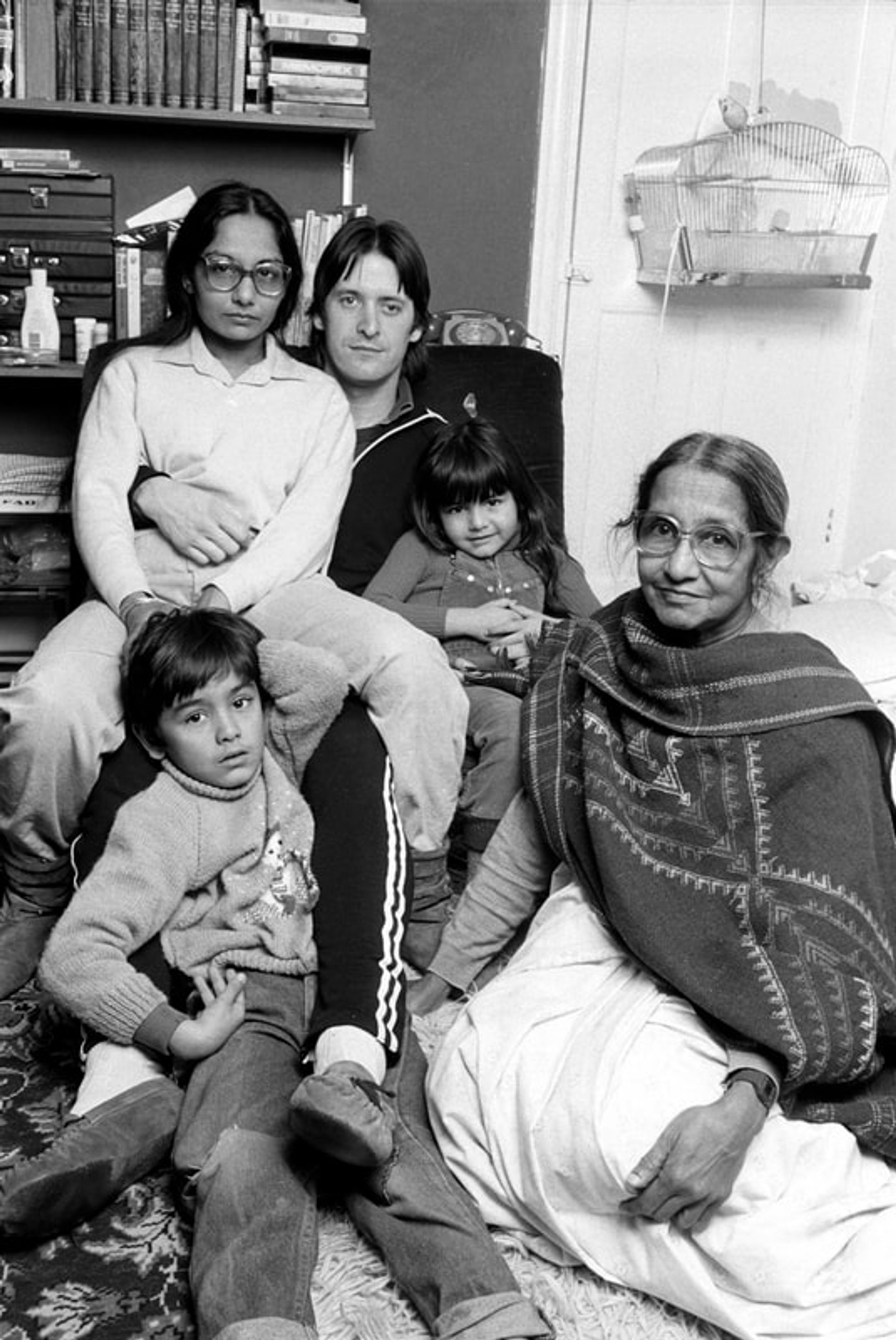

Untitled, from the series Reflections on the Black Experience (1986) © Sunil Gupta

“Sunil and I were forged in the era of the GLC" says the show’s curator Mark Sealy. The Greater London Council (GLC) was notable for its high social welfare spending before it was dissolved by Margaret Thatcher in 1986. "We are of community-based politics," he adds. “It is Sunil’s active engagement with his newfound homes that sets him apart from so many others. He has never been a mere observer.”

The effects of this engagement can still be seen today. His series of reportage works, such as Reflections on the Black Experience (1986), played a crucial role in the creation of Autograph ABP, a UK-based photography organisation founded in 1988 to fight discrimination within the industry and exhibit culturally diverse artists such as Rotimi-Fani Kayode, Ingrid Pollard, and Gupta himself.

Shroud / Pleasuredrome, from the series From Here till Eternity (1999) © Sunil Gupta

This activism extends past race too. Diagnosed with HIV in 1995, the show’s title takes its name from a 1999 series of six diptychs in which Gupta documents a bout of illness brought on by the virus.

Also presented in the show is ephemera from Gupta’s life—published as a new book—which includes pamphlets from Aids activist meetings at the height of the crisis and posters for queer support groups such as the Gay Switchboard. These markers of physical community might seem like relics for today's generation of queer Londoners who occupy a city of hookup apps and reduced civic space.

“People seemingly believe we are now in a post-Aids moment," Gupta says. "And if you are wealthy, white and lucky, that might even be the case. But there is something more depressing about today's return to rampant sexuality. This time the politics are less clear. I don’t think these people are feeling that revolutionary.”

Bikram, from the series Mr Malhotra's Party (2007) © Sunil Gupta

Indeed, a radical political identity has always been embedded within Gupta’s sexual one. “I came of age during Gay Liberation, when gayness meant difference, not assimilation. We were bad. We wanted to have sex all the time and in doing so we fought against the traditional family structure and the accumulation of property."

Gupta's global upbringing has also occasionally put him at odds with his peers who stayed in the country. Returning to India for the first time after a long stint in New York, he once again looked to turn his camera towards queer life. But in stark contrast to Christopher Street he found gay men "hidden in plain sight". His 1983 series Towards a Gay Indian Image features gay Indian couples amid expansive backdrops, their faces concealed.

Even when he moved back to a newly liberalised India in the early 2000s, he noted that many Indians had somehow "missed" the global LGBT movement and its corresponding hard-fought-for identities. "Gay meant something different there. In Delhi I’d sometimes meet men who'd tell me they're 'gay' and I’d think—'you’re not gay, you’re a guy married to a woman who has sex with other men'".

If you can’t stand the heat ... Untitled #9, 2010, from the series Sun City Photograph: Sunil Gupta

This complex relationship with his home country forms one of the show's most compelling narratives, as does his navigation of a Western gay scene that denies visibility to HIV positive South Asians. The fraught nature of desire within marginalised bodies is examined in his 2010 series Sun City, in which an Indian man arrives in Paris to meet his lover and experience a Western bath house. “I wanted the series' protagonist to be hairy and short, not tall and sleek. We don’t come fresh off the boat looking like runway models”.

"I think what he's been looking for is affection"Mark Sealy, curator

In 2012, when Sun City was exhibited at the Alliance Francaise Gallery in New Delhi it was shut down by police, being deemed “obscene” and “against Hindu culture”. But Gupta was not particularly fazed by the experience. Fitting in has never been part of his agenda. Instead, his work has so often explored the liminality experienced by diasporas—an existence marked by longing, confusion and, at best, a tenuous acceptance into the mainstream.

"I think what he's been looking for is affection," Sealy says. "Even in his Christopher Street series, activity that was so often seedy and dangerous is rendered romantic." And it is true, Gupta's lens never really leaves the halcyon days of the cruising ground. The exhibition's tender collections of images are fascinated with human relationships—his boyfriends, his families both biological and chosen. And even at their bleakest, they are charged with the jolt of promise. In the realm of Gupta's photography there always exists the chance that a furtive glance might lead to a night of passion, and a casual encounter to a lifetime of love.

This exhibition is sponsored by the Bagri Foundation.

• From Here to Eternity: Sunil Gupta. A Retrospective, The Photographers' Gallery, London, 9 October-21 January 2021