Photographs of military camps and bleak landscapes taken by Roger Fenton (1819-69) during the Crimean War were first displayed 160 years ago in an impressive, 26-venue tour across the UK. The hardships of the conflict—reported in newspapers and illustrated journals—were well known at the time and would have been at the forefront of people’s minds when viewing the images.

This week an exhibition at the Queen’s Gallery in London, of more than 60 of Fenton’s original salted paper and albumen prints, reveals how these early photographic representations of conflict shaped public consciousness about the human costs of war and continue to resonate with war photographers today.

Now considered one of the first war photographers, Fenton was in fact commissioned to travel to Crimea to create an extensive photographic record of senior officers, to be used as source material for a large history painting by Thomas Jones Barker, made to be commercially reproduced as a mezzotint. Many of the major battles had already taken place by the time Fenton arrived in 1855, and because of the technology available his photographs do not show action, but are predominantly posed portraits and desolate landscapes.

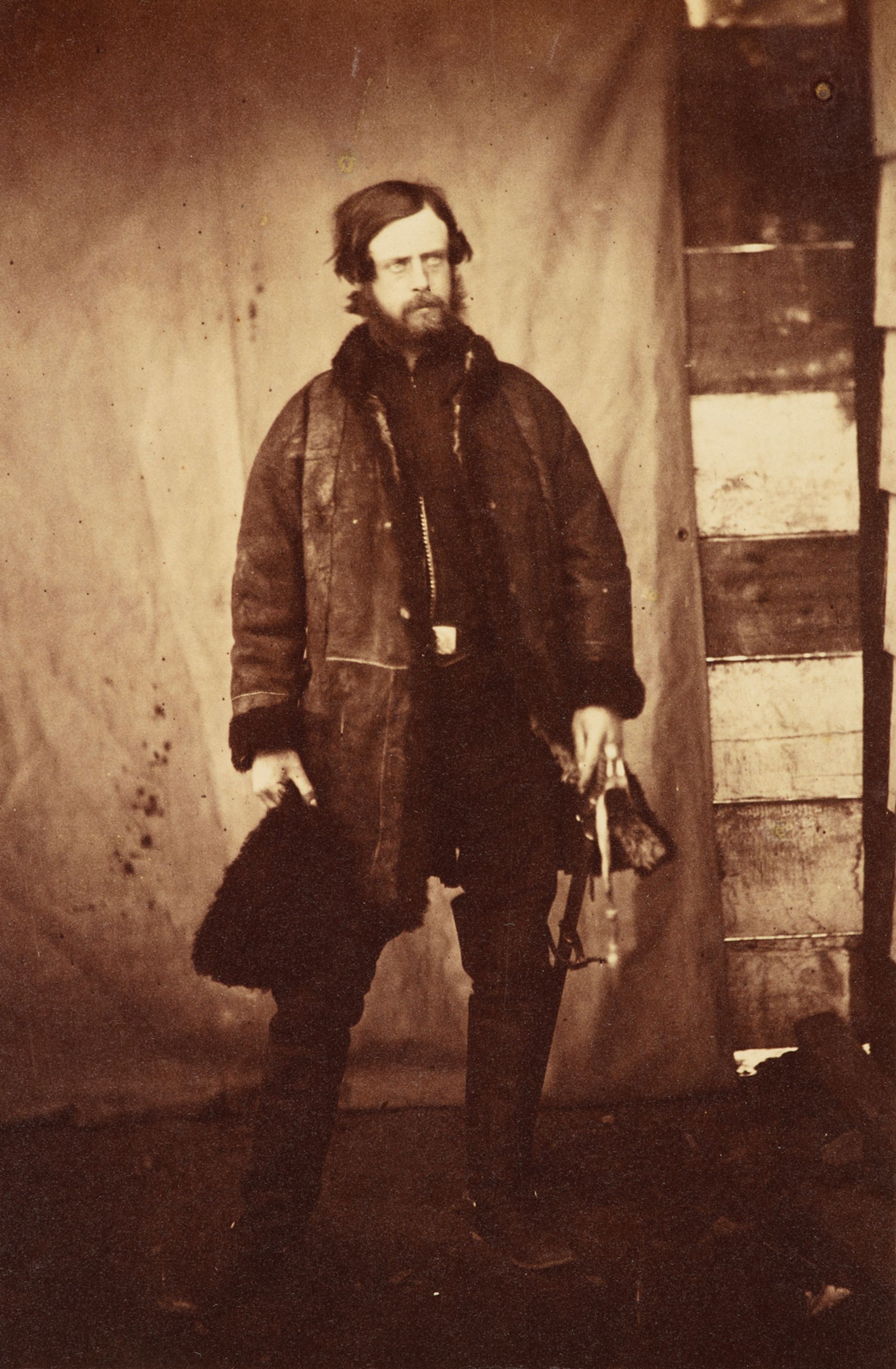

Roger Fenton’s “shell shocked” Lord Balgonie (1855) © Royal Collection Trust; Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

Despite these limitations, Fenton’s images still had the power to move the viewing public, who would have known “when they looked at these battlefields, what happened there, and were probably populating the photographs with their imagination”, says Sophie Gordon, the exhibition’s curator and head of photographs at the Royal Collection Trust.

One such image in the exhibition, and arguably Fenton’s best-known work, is Valley of the Shadow of Death (1855), which depicts an empty landscape traversed by a rough road strewn with cannon balls. (Another photograph with the same title shows the road without the cannon balls, which has led to speculation that Fenton may have arranged them for a more affecting scene.) The subtle, implied threat and evocation of past events give the image its enduring power. This approach, eschewing spectacle and sensationalisation, has provided a model for later war photographers, such as the Northern Ireland-born Paul Seawright, whose photograph Valley (2002)—from the series Hidden, taken during the war in Afghanistan—directly references Fenton. Echoes of Fenton’s methods can also be seen in the work of the English photographer Anastasia Taylor-Lind. Her improvised portraits of fighters and mourners, Maidan—Portraits from the Black Square (2014), were created in a makeshift studio in Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) during the Ukrainian revolution (an event that precipitated the annexation of Crimea by Russia the same year).

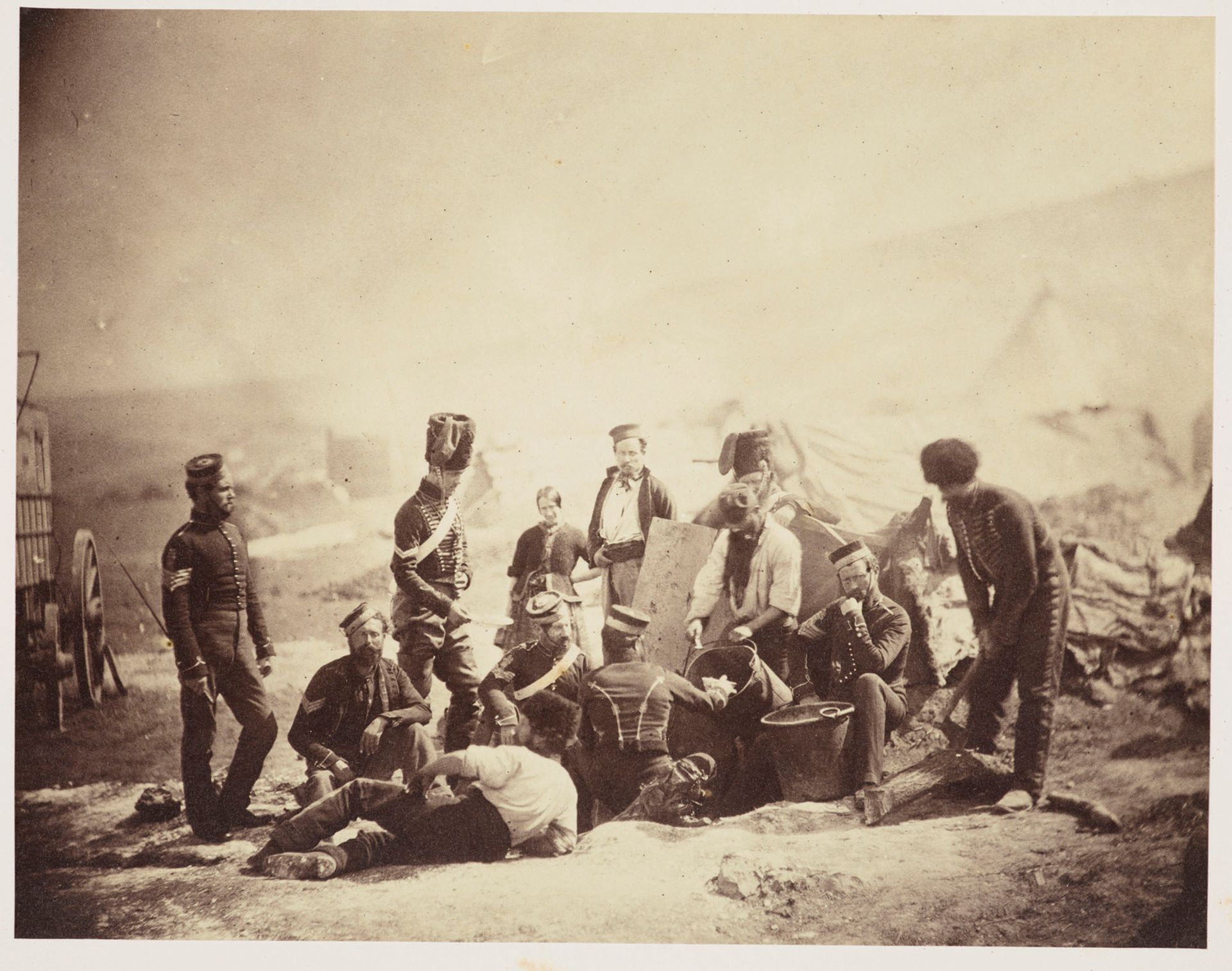

Roger Fenton's 8th Hussars Cooking Hut (1855) © Royal Collection Trust; Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

The Queen’s Gallery exhibition emphasises the contribution of Fenton’s photographs to growing public sympathy for returning soldiers, physically and psychologically affected by the war. Lord Balgonie (1855), a haunting portrait that Gordon describes in the exhibition catalogue as showing someone appearing to suffer from shell shock, represents a departure from Fenton’s formal portraits of neatly uniformed officers. According to Gordon, this “fits in with the idea that Fenton is emotional and also quietly subversive. He’s certainly not out to whitewash the war and present it as a wonderful British victory.”

• Roger Fenton’s Photographs of the Crimea, Queen’s Gallery, London, 9 November-28 April 2019

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert by Roger Fenton (1854) Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

The royal connection continues

Britain’s Prince Harry, who served in the armed forces, has contributed to the audio guide accompanying the Roger Fenton exhibition, highlighting the close relationship between the royal family and returning soldiers that was first established by Queen Victoria during the Crimean War.

The curator Sophie Gordon explains that, not wanting her response to be overshadowed by Florence Nightingale, who had organised the nursing of soldiers in Crimea, Victoria “stepped up to present herself […] as the mother of the nation and the mother of the troops, by actively visiting the wounded men in the hospitals and ensuring that artists and photographers were on hand to document these visits”. The exhibition includes paintings and photographs commissioned by Victoria herself, which help to position Fenton’s work as “part of an unfolding tragic story about war, conflict and our response to wounded soldiers”.