Few in the West would have heard of the Gwangju Uprising—a South Korean massacre that began in 1980 as a peaceful, pro-democratic protest and resulted in 2,000 deaths after the government imposed martial law across the country.

The pivotal event can be seen as a regional precursor to the comparable murderous crackdown in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square nine years later. But, unlike the events in China, the Gwangju Uprising turned out to be a major stepping stone towards South Korea’s transition from a militarised and deeply oppressive autocracy to the vibrant, internationalist and progressive democracy of today.

“We are interested in learning from the struggle, not fetishising it”

The Gwangju Biennale—launched in 1995 in the country’s sixth most populous city—was founded in part to explore the heterogeneous impact the uprising has had on South Korean society. This year, as South Korea confronts the legacy of the uprising four decades later, the biennial will “respond in quite direct terms” to how the event remains “live, non-historicised and tangible,” say the co-artistic directors Defne Ayas and Natasha Ginwala.

Visitors in line at the 1st Gwangju Biennale in 1995 Courtesy of the Gwangju Biennale Foundation

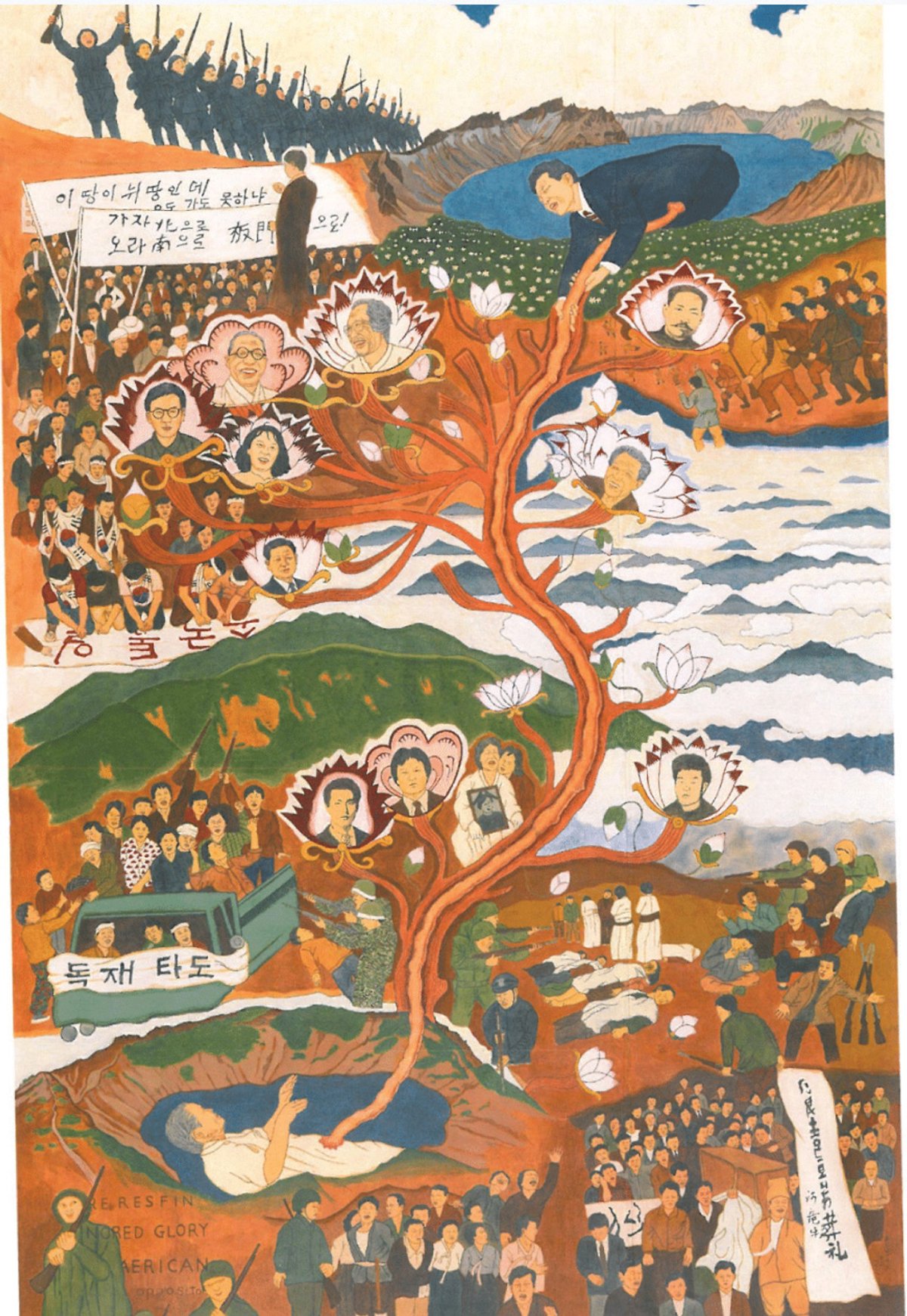

The biennial, titled Minds Rising Spirits Tuning, opens this week and includes 69 participating artists, many from Korea and the surrounding region such as the documentary photographer Gap-Chul Lee and the painter Sangho Lee, with 41 new commissions at numerous sites throughout the city.

Due to the pandemic, the biennial has largely been curated and produced remotely (primarily over Zoom) across seven different countries. “For people who participated in 1980, the trauma continues to circulate,” says Ginwala, speaking from Sri Lanka. “But there’s an amnesia and detachment from the event for younger generations, and a culture of denial amongst certain sections of society.”

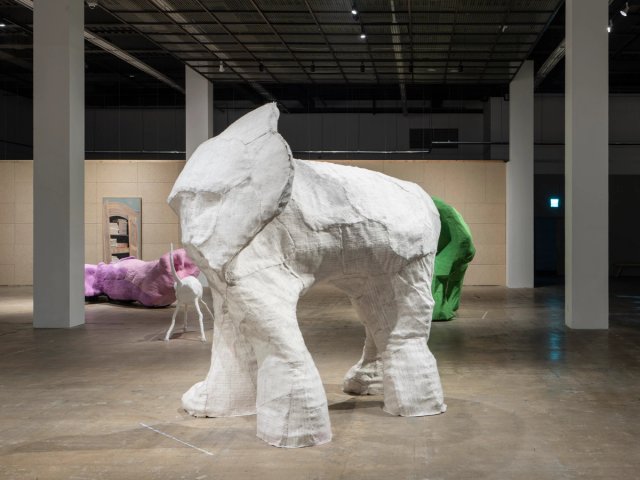

Candice Lin's Papaver Somniferum (Tapestry) Courtesy of the artist

Ayas and Ginwala note the way the uprising has often acted as a litmus test for truth-telling between Korea’s conservative and progressive movements. Some far-right groups continue to deny the existence of the event altogether, or try to assert conspiracy theories on accepted historical fact. Other traditionally marginalised communities who participated in the uprising have also struggled to seek acknowledgement or recognition for their role in the democratic movement.

In a deeply patriarchal society, the integral role of women and minorities in the uprising has also been repudiated by a mainstream and official culture of remembrance that instinctively reverts to the Korean male gaze, the directors say. This institutionally gendered process of remembrance alongside an Orwellian phenomenon of historical abstraction has clear modern-day reverberations in the Western world.

But yet, in an era in which performative and spectacle-based resistance movements have become de rigueur across cultures and continents, the biennial will also explore how the uprising has influenced the visual aspects of protest today.

Brier and Old Woman, Hapcheon (1994) by Lee Gap-chul

“At this moment in our history, there are various civic movements, uprisings, revolutions and riots in almost every corner of the world,” Ginwala says. “It was very important for us to not historicise the uprising as something that is separate and finished, but to regard it as something that is perhaps volatile, a space of inspiration and resilience and strategy building for other such movements in India, Turkey, Chile or Brazil. We are interested in learning from the struggle, not fetishising it.”

A key aspect of Ayas and Ginwala’s curation has been an engagement with the Gwangju archive, “a minute-to-minute chronicle of the uprising, and a granular example of how a civic movement can be memorialised and archived,” Ginwala says. “The role of journalists, the role of mothers and the role of students—they’re all chronicled in that archive.” This, Ayas says, helped the biennial to confront “the hierarchy of suffering, the question of who gets remembered, and how they are remembered—as victims, or as heroes.”

• Gwangju Biennale: Minds Rising Spirits Tuning, various venues, Gwangju, 1 April-9 May