When Sophie Taeuber took to a Zurich stage in 1917 (long before marrying Jean Arp and, as per Swiss custom, tacking his name onto the end of hers), the Cabaret Voltaire and Dada founder Hugo Ball sat in the audience and watched her dance. He saw a goldfish, darkness, questions, a child, an angel, invention, caprice, wit. “Sophie Taeuber,” he later wrote, “is completely different”.

The major survey Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstractions, which opens this week at the Kunstmuseum Basel, is dedicated to the miraculously unfixable career heralded by that performance. The exhibition will travel to New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in the autumn—the Swiss artist’s first US survey in 40 years—by way of London’s Tate Modern in July. The latter will be a first ever for the British public, which, save for a couple of works on paper in the Victoria and Albert Museum and one small collage at the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich, has no access to her work.

A 1920 photo of Sophie Taeuber-Arp by Nic Aluf Arp Foundation

Since a generous donation of more than 100 works from the Arp Foundation in 1968, Taeuber-Arp has been the cornerstone of the Kunstmuseum’s Modern offering. But the museum’s strict cleaving to traditional fine art categorisation means none of her applied arts output is included in the collection. This exhibition, by contrast, will aim to show the artist in the round: a multi-hyphenate before her time, a cross-pollinating abstractionist arriving fully formed and entirely untethered to figuration, a force to be reckoned with.

The show will start with Taeuber-Arp’s earliest works on paper and the remarkable colour-field beaded bags she made in the 1910s (a traditional craft that had, until that point, remained largely unchanged for hundreds of years). From there it will expand—as she did—into illustration, textiles, costumes, stained glass, turned wood, marionettes, painting, performance, dance, drawing, sculpture, architecture... a body of work as superficially heterogeneous as it is intrinsically coherent.

Taeuber-Arp's marionette King Stag: Stag (1918) Courtesy Museum für Gestaltung, Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, Zurich; Image courtesy of Umberto Romito and Ivan Suta.

“The dream,” as the MoMA curator Anne Umland puts it, is that visitors will be able to watch these elementary geometric shapes move across it all, “and see how exactly abstraction is part of our world”.

Although only the New York iteration will feature MoMA’s Dada Head from 1920 (as one of only four extant Head sculptures, it cannot travel), Taeuber-Arp’s marionettes will be a highlight of all three shows. Tristan Tzara in 1922 noted the “real sensation” they had caused when first exhibited. A new film made with Zurich’s Museum für Gestaltung now sees them set in motion once again.

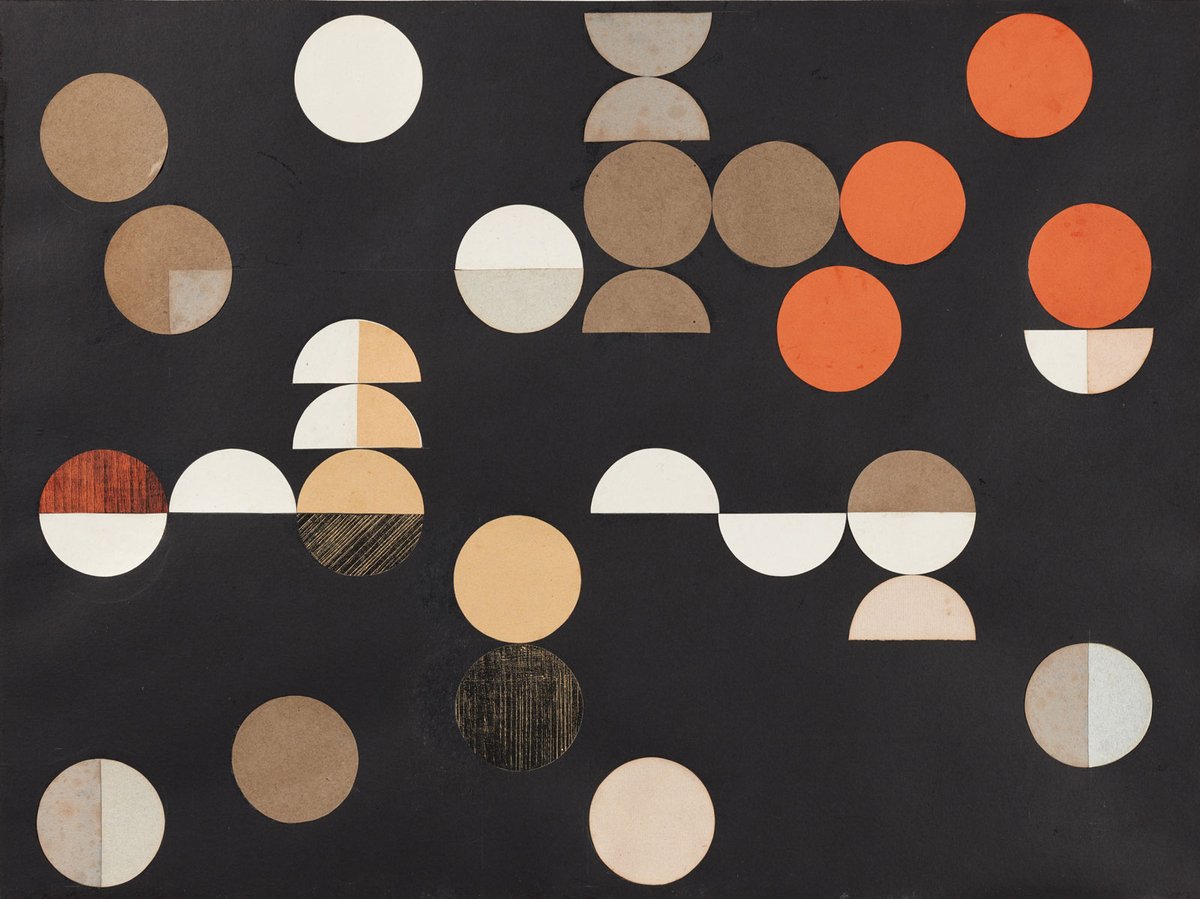

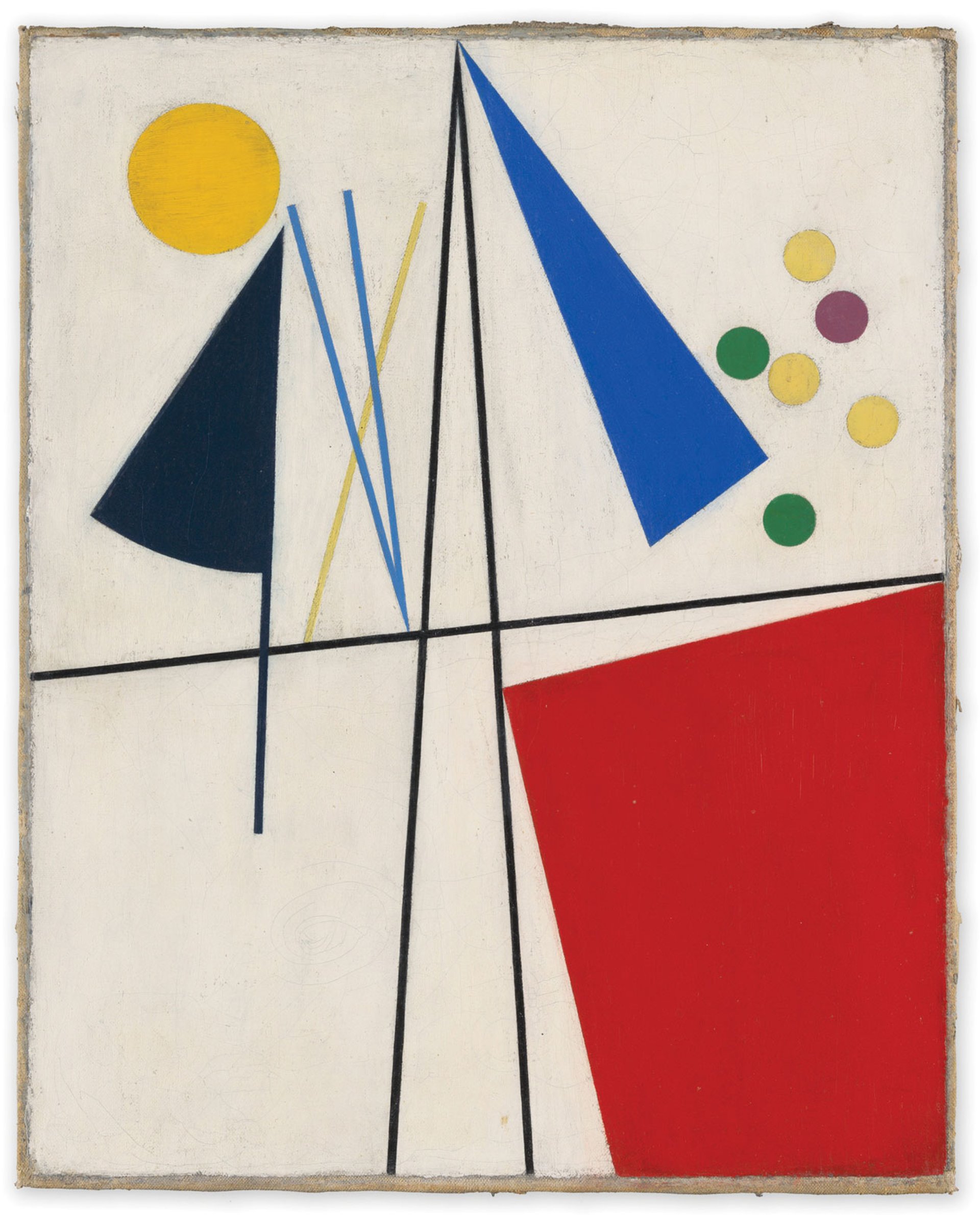

Taeuber-Arp's Equilibre (1932) © Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth; Photo: Alex Delfanne

Taeuber-Arp is of course routinely written about in connection with the Zurich avant-garde, though always in the shadow of her more famous husband. Arp called her his muse, but she was so much more than that. She was also the breadwinner and worked as a teacher for 12 years in the Applied Arts Department of Zurich’s Trade School. She was only able to quit the job after she and Jean won an architectural commission to redesign the Aubette complex in Strasbourg. They used the money from this commission to buy some land outside Paris to build a house, which Taeuber-Arp designed, but had to flee at the onset of the Second World War.

Taeuber-Arp’s painting Farbige Staffelung (coloured graduation, 1939) © Museum of Fine Arts Bern, Switzerland, all rights reserved

This exhibition, rightfully billed as long overdue, will be an investigation into both Taeuber-Arp’s work and its reception since her accidental death from carbon monoxide poisoning in 1943. One only has to juxtapose the tremendous ambition on display in every piece with the way in which the death certificate recorded her as merely “a housewife”, to gauge what she was up against—not to mention the two World Wars, global recession and pandemic she lived through.

Her polymathic activities, as Umland writes in the catalogue, make her feel exceptionally contemporary. Hers was a radical playfulness born of necessity, and a clear-eyed determination to make art, no matter the form, against all the odds.

• Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction, Kunstmuseum Basel, 20 March-20 June; Tate Modern, London, 15 July-17 October; Museum of Modern Art, New York, 21 November-12 March 2022