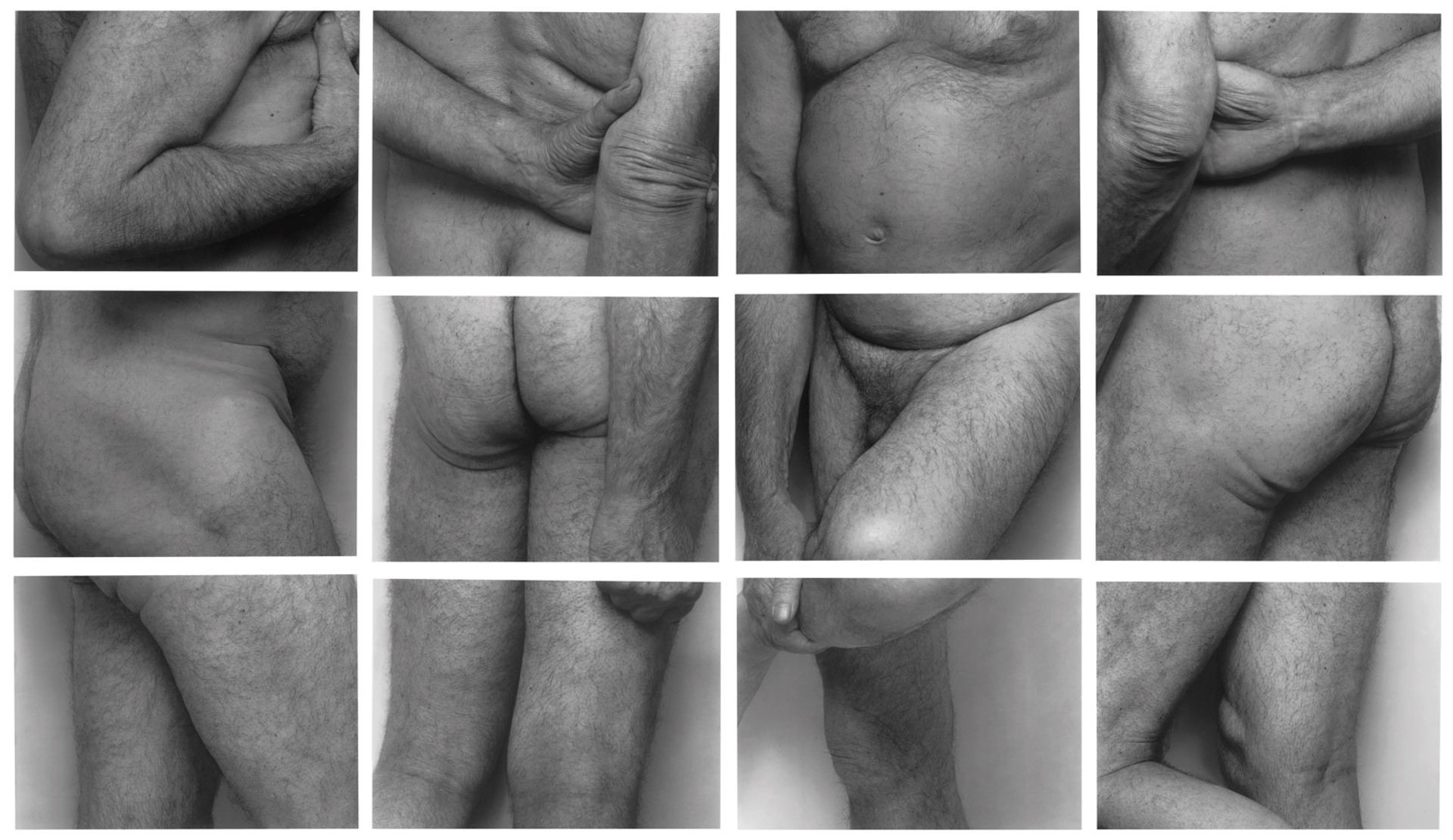

A large frieze of the artist John Coplans’s naked body will open Masculinities, a major photography exhibition comprising more than 300 works at London’s Barbican. Coplans began taking black-and-white photographs of himself when he was 60 years old. Yet he never revealed his face in his images, instead contorting his body—loose and flabby, latticed with hair, skin the pallor of chalk—to create an abstracted representation of the male physique in the throes of age. The image works as an explicit example of the show’s subtitle: Liberation through Photography.

The show’s curator Alona Pardo hopes we will feel liberated to question the relative and pluralist nature of what is often talked of as the most binary of states: to be a man, as opposed to a woman.

The exhibition, Pardo says, “is calling for a total rethink of gender”. After reading Gender Trouble (1990) by the US philosopher Judith Butler, Pardo says “[I] really aligned myself with the idea that we’re not biologically defined. We learn to perform our genders, and those are determined by society. But masculinity is a plural thing; it changes and it varies according to historical periods, geo-political spaces.”

The show will include the work of more than 60 photographers active from the 1950s onwards, with the earliest images coming from Karlheinz Weinberger’s Rebel Youth series, while the most recent will be by the US non-conforming trans artist Elle Pérez, completed in late 2019.

John Coplan's Self-portrait (Frieze No. 2, Four Panels), (1994) © John Coplans Trust

The photographs here expose masculinity as a malleable and fluid construct—one that morphs and changes across era, generation and culture. It explores how masculinity is often learnt through practice, communicated via performance and amplified through popular culture. But in reality, masculinity eludes simple definition through endless subtle variations. In that, Pardo says, the show acts a counter-balance to the established order of things.

“There is a gender hierarchy, and that is dominated by an ideal of masculinity which is defined by a white cis male,” Pardo says. “Absolutely everything around us, you begin to realise, is gendered in that way—so, of course, it has to be a social construct. But that’s also something we can push against. Men are allowed to be humans, to be individuals, to express emotions, to be aware of mental health, to welcome in a much more inclusive landscape in which to present their identity and their gender.”

The exhibition will include images by some of art’s most famous practitioners: Robert Mapplethorpe’s images of a then little-known bodybuilder called Arnold Schwarzenegger will be included, as well as masculine-centric images by Andy Warhol, Richard Avedon, Jeremy Deller, Richard Prince, Wolfgang Tillmans and Catherine Opie.

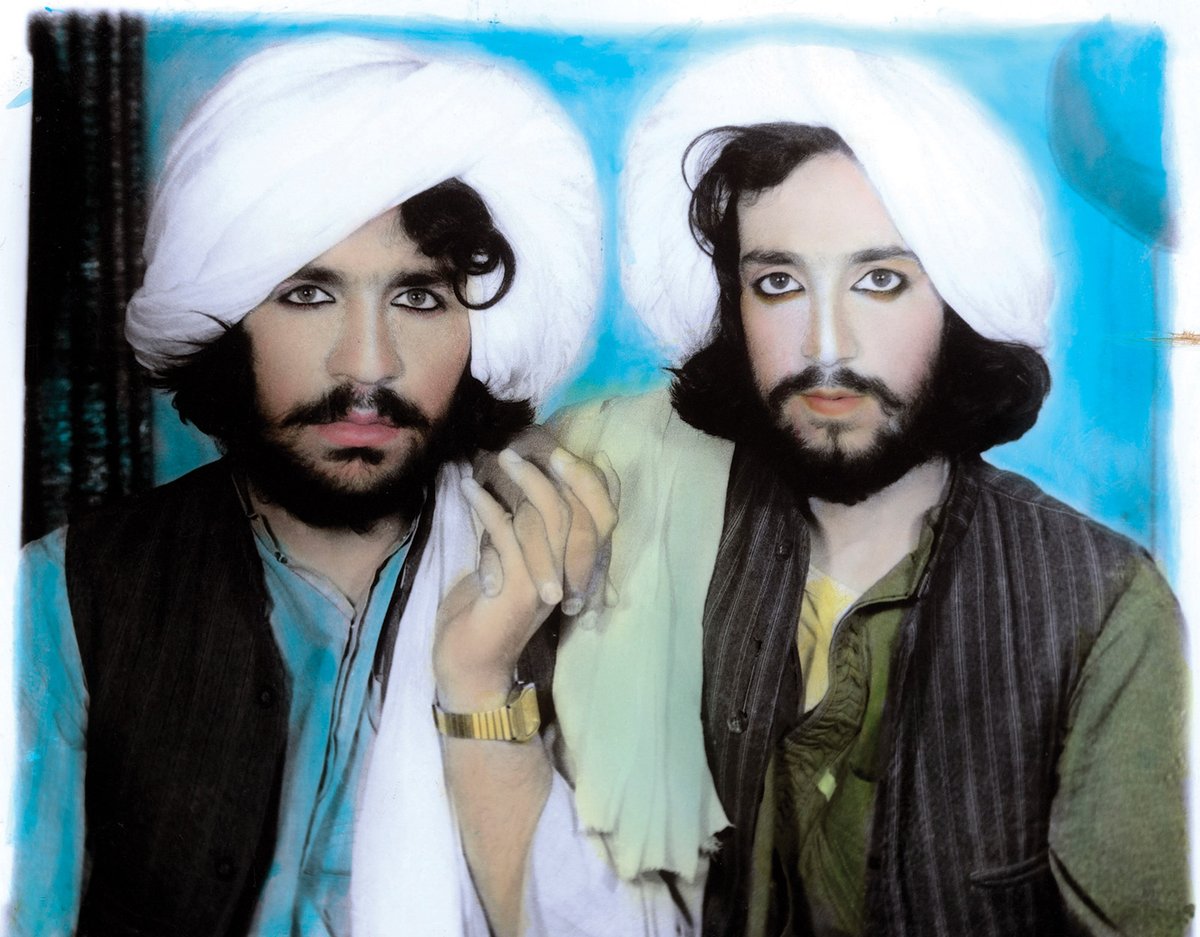

Yet the most interesting work comes from lesser-known names, not least the work of Thomas Dworzak, the current president of the Magnum Photos agency, who, a few months after the start of the US war in Afghanistan in 2001, discovered in the back rooms of the one working photo shop in Kandahar a trove of era-defining self-portraits. Under the Taliban, photography was forbidden throughout Afghanistan. But soldiers were allowed to take passport photographs. The Taliban militia took advantage of this liberty, using the privacy of the photo booth to create remarkably ambivalent variations on the kind of masculinity being imposed on them. They posed hand-in-hand in front of idyllic painted backdrops, with flowers in their hair and kohl lining their eyes. The resulting book, Taliban (2003), Dworzak notes, is popular in Berlin’s queer bookshops.

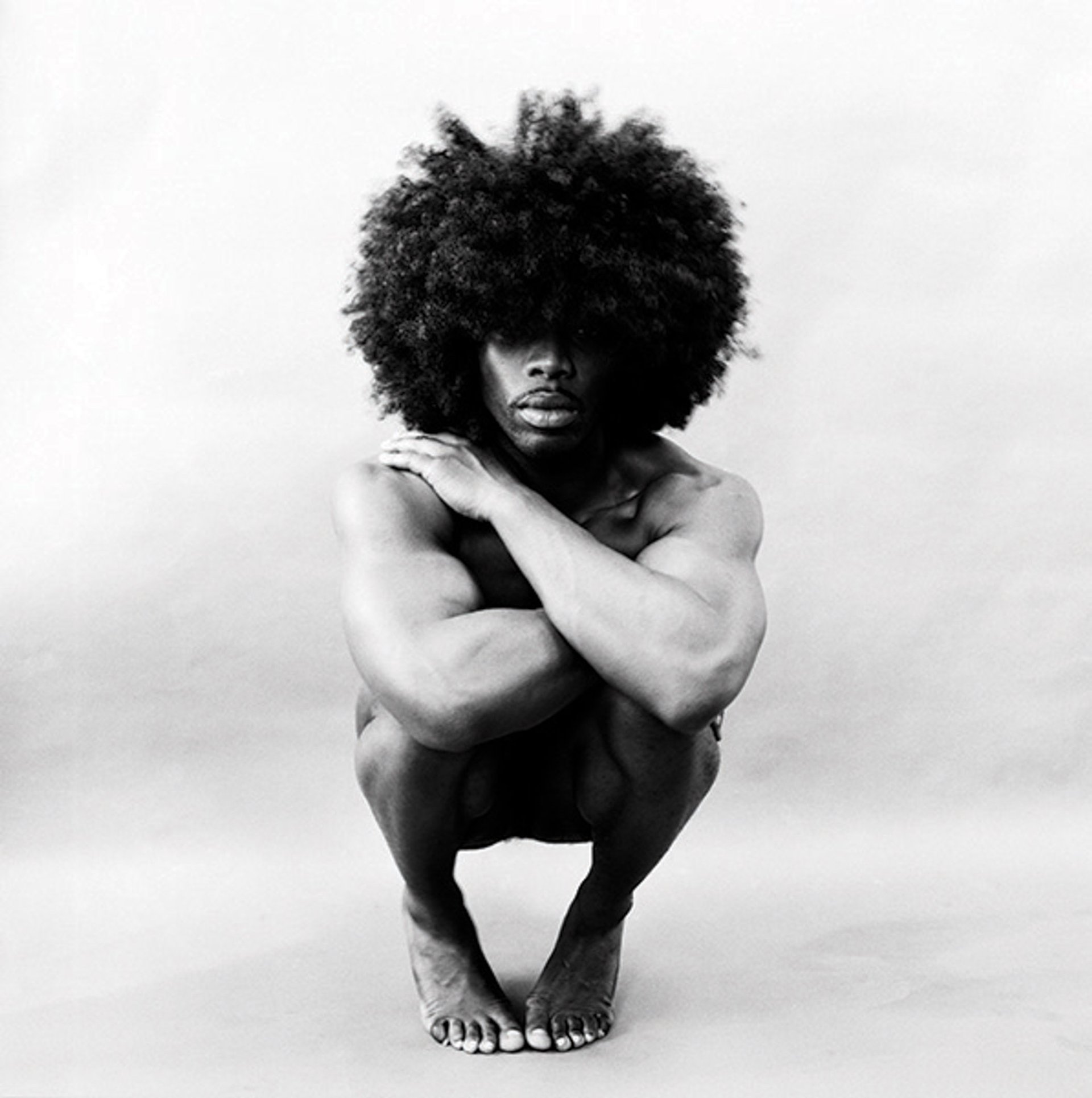

Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s Untitled (1985) © Rotimi Fani-Kayode/Autograph ABP

Also on show will be Richard Billingham’s portraits of his own father, Ray, a wizened, alcoholic hermit who lived in a high-rise flat in the urban sprawl beyond Birmingham. The images, first exhibited in Charles Saatchi’s Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1997, were revisited by Billingham in 2018 in the form of a debut feature film that won numerous accolades at the British Independent Film Awards.

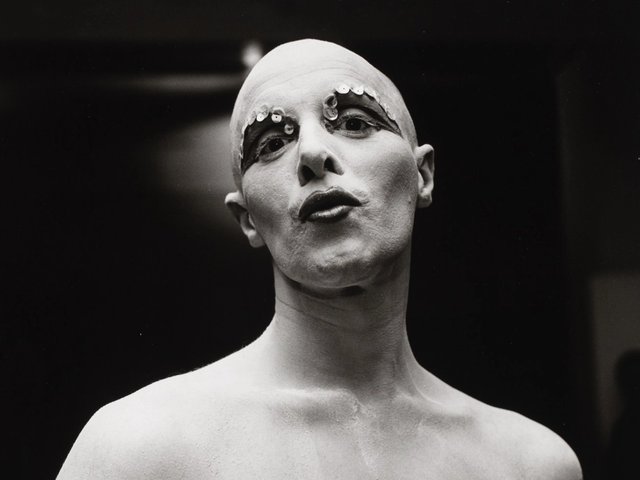

Then there is the little-known British Nigerian photographer Rotimi Fani-Kayode, a one-time New York contemporary of Robert Mapplethorpe. Born in 1955 in Lagos to a prominent Yoruba family, Fani-Kayode arrived in Brighton as an 11-year-old refugee escaping the Biafran war. Fani-Kayode was rejected by his family after he came out, so he left Britain to study in America. He referred to his sexualised, performative self-portraits, which often incorporated elements of Yoruba folklore, as “a weapon, if I am to resist attacks on my integrity and, indeed, my existence on my own terms”. Fani-Kayode died from an Aids-related illness in London in 1989, at just 34 years old. More than 30 years later, it is heartening to see his fiercely physical and defiantly discursive statements of black, queer masculinity on the national stage of his adopted home.

The exhibition’s main sponsor is Calvin Klein.

• Masculinities: Liberation through Photography, Barbican Art Gallery, London, 20 February-17 May