Since founding Art & Newport in 2017 to mount site-specific contemporary art installations at unusual locations across her hometown in Rhode Island, the writer and curator Dodie Kazanjian has had her eye on the Belmont Chapel in Island Cemetery near her family's burial plot.

“I grew up afraid of that building and at the same time fascinated with just wanting to go into it,” says Kazanjian, of the intimate Neo-Gothic chapel commissioned by the financier and Newport patron August Belmont Sr, in memory of his daughter Jane who died in 1875 at age 19. Opened in 1886 for internment services, the building had fallen into severe disrepair over time and was entirely shrouded in vines by 2014, when a foundation was formed to begin its restoration. Kazanjian toured the partially repaired structure for the first time in December and convinced its trustees to lend it for a project.

“It felt haunted yet also strangely inviting and calling out for an artist to occupy,” says Kazanjian, who brought in the Warsaw-born, Brooklyn-based conceptual artist Piotr Uklanski because of his ability to inhabit environments that reverberate with history. His new series of portraits titled Suicide Stunners' Seance, installed like jewels on the chapel's distressed walls peeling with paint, is on view for free from 3 July through Labor Day, Fridays to Sundays, noon to 8pm.

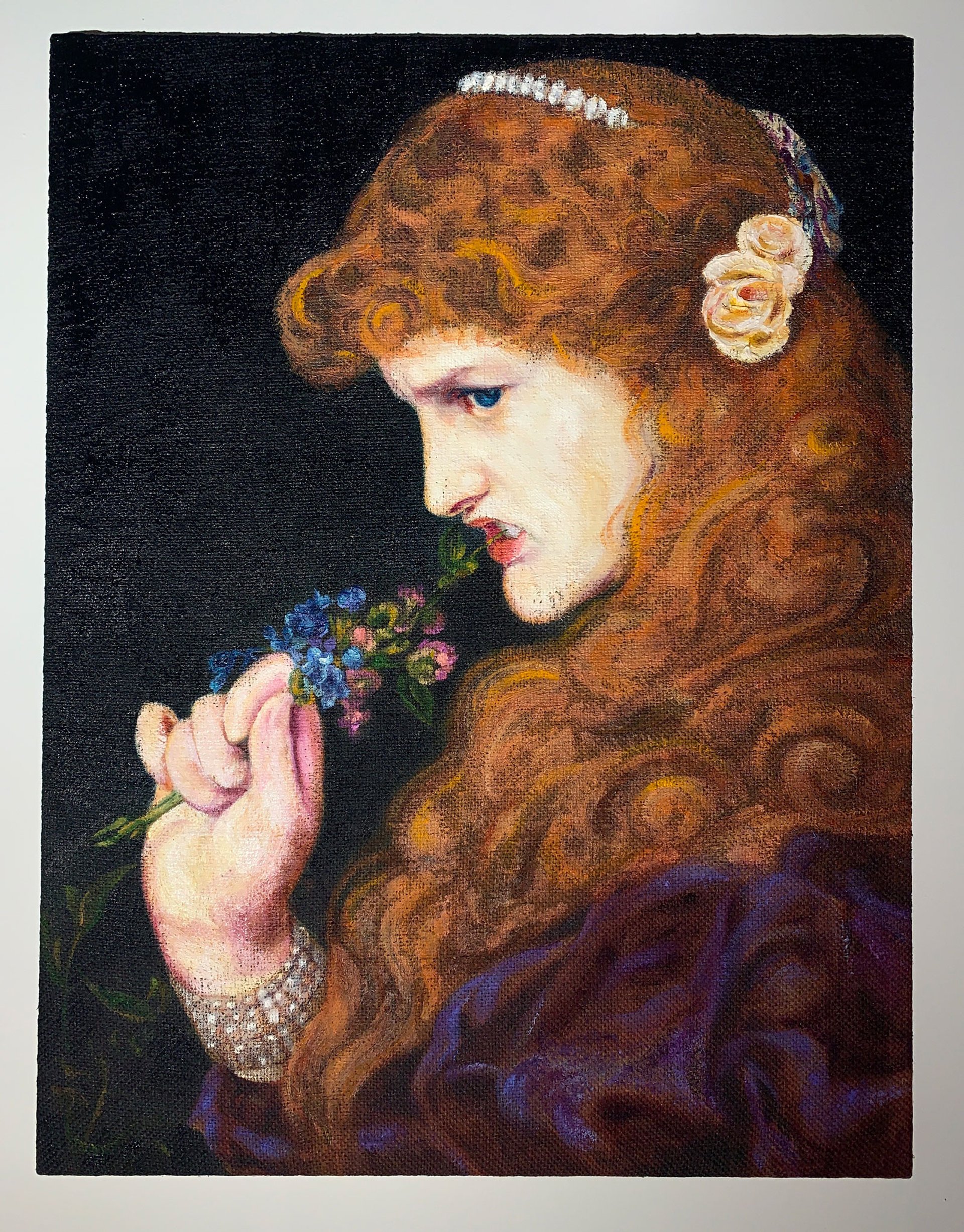

Piotr Uklanski's portrait of Emma Jones

Responding to the ambiance and lore of the chapel, with a stained glass window above the alter depicting Jane Belmont being carried aloft by angels, Uklanski has drawn a parallel to the real-life women painted by the Pre-Raphaelites. This all-male society of artists prized fair red-haired models to depict ill-fated characters from literature such as Pandora and Helen of Troy and worked in 19th-century England contemporaneously to Jane's short lifetime.

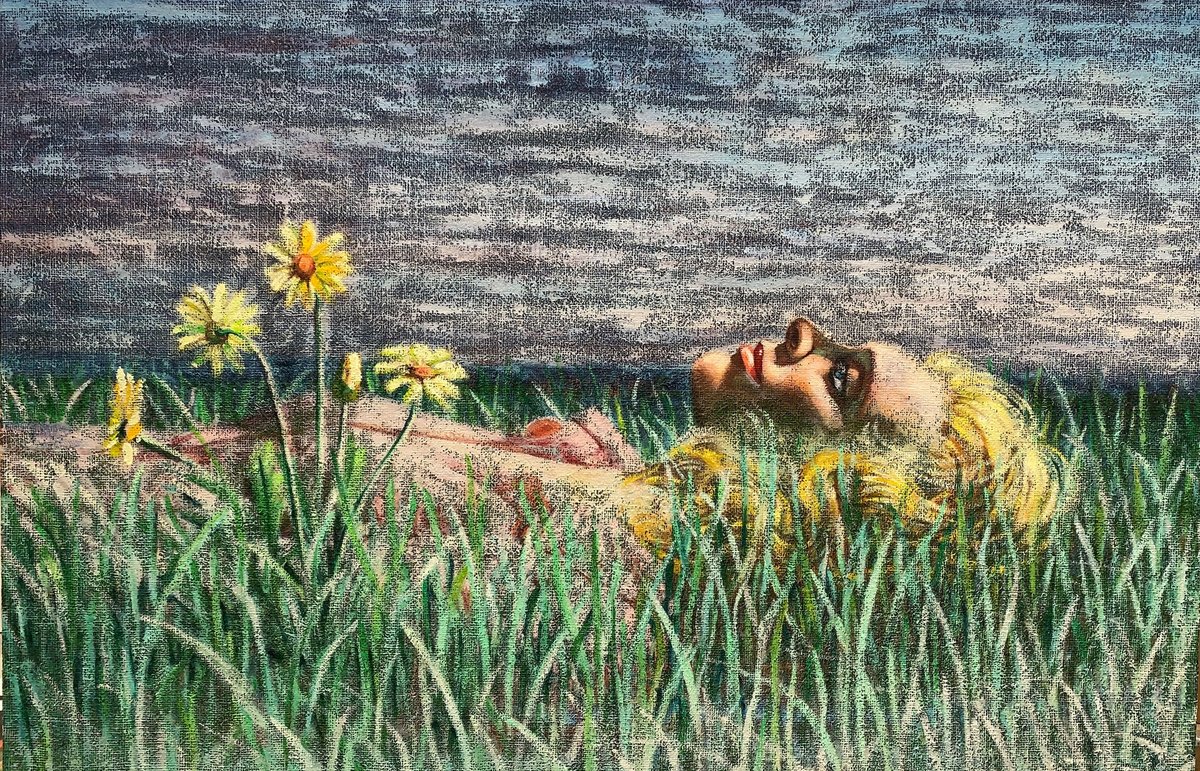

Known for his use of appropriated imagery in a range of media, including his 1998 collection of film stills of actors performing as Nazis, Uklanski here has remade historical paintings of the Pre-Raphaelite muses called “stunners” in their day. His portraits foreground Elizabeth Siddall (married to one of the movement's leaders, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and immortalised as a drowned Ophelia in John Everett Millais's famous painting), Annie Miller, Emma Jones and Jane Morris (who married Rossetti after Siddall's suicide), among others.

Piotr Uklanski's portrait of Jane Morris

“Over the centuries, images of women with red hair symbolize some sort of threat—on the one hand they were seen as hyper-sexualized; on the other they were the witches,” says Uklanski, 51, who has accentuated the agency and personality of each of the women in his paintings and restored the original spelling of Siddall's name with two l's, changed by Rossetti to suit some image he wanted to project. A painter and poet in her own right, Siddall got caught up in medicating herself to inspire the attentions of her neglectful husband, according to a biography by Lucinda Hawksley, and ultimately killed herself in 1862 at age 32.

“This was perhaps the only statement she could make at the time she lived in to reflect upon the inequality she found herself in in the relationship with Rossetti as an ambitious artist herself,” says Uklanski, who was left to imagine stories of Jane Belmont about whom less is known. “After I started doing the paintings, it was almost like a seance, calling for the ghosts of who these women really were.”