If you happen to be walking through downtown Kyoto this autumn, be on the look-out for townhouses, shopping arcades and workshops that stand out from the crowd. Step inside and you will discover a series of exhibitions revealing sides of Japan and the region rarely acknowledged or understood in the West.

This is the eighth edition of Kyotographie, Kyoto’s annual photography festival and Japan’s leading platform for the medium. At a historic machiya townhouse in the Shimogyo-ku area, one might stumble upon Bento is Ready, a portraiture-based exploration of Kyoto’s ageing poor by Atsushi Fukushima, a photography student who, after graduating, worked as a Bento box delivery man for some of Kyoto’s most vulnerable residents. During his rounds, he carried a camera around his neck. “At first, I felt like I was facing death,” Fukushima writes. As he slowly developed relationships with those he visited, so he began to take their portrait. “As I continued shooting over many years,” he says, “I began to feel I was facing life.”

One of the images from Atsushi Fukushima's Bento is Ready series © Atsushi Fukushima

Further down the road, at a traditional obi textile workshop, there will be an exhibition dedicated to the Hong Kong photographer Wing Shya, perhaps China’s most celebrated fashion and film photographer. Wing is also well known in Asia for his work documenting the film sets of the Chinese movie director Wong Kar-wai, in particular his masterpiece In the Mood for Love (2000). The director recruited the young photographer after he came to prominence for his moody, saturated and sometimes blurry images that were often dismissive of Chinese artistic heritage.

The forthcoming Wing retrospective has been curated by Karen Smith, the co-founder of the Shanghai Center of Photography, and will include little-seen personal work from the 56-year-old’s four-decade career, orientated alongside his now famed film shots. “Wing is a master at developing rapport with his subjects. Nothing in the images ever feels staged,” Smith says. “Even when they are at their most surreal, they speak directly to the mood of the moment captured, as much as to the personality who appears in the frame, or the dynamics that clearly spark when several figures come together.”

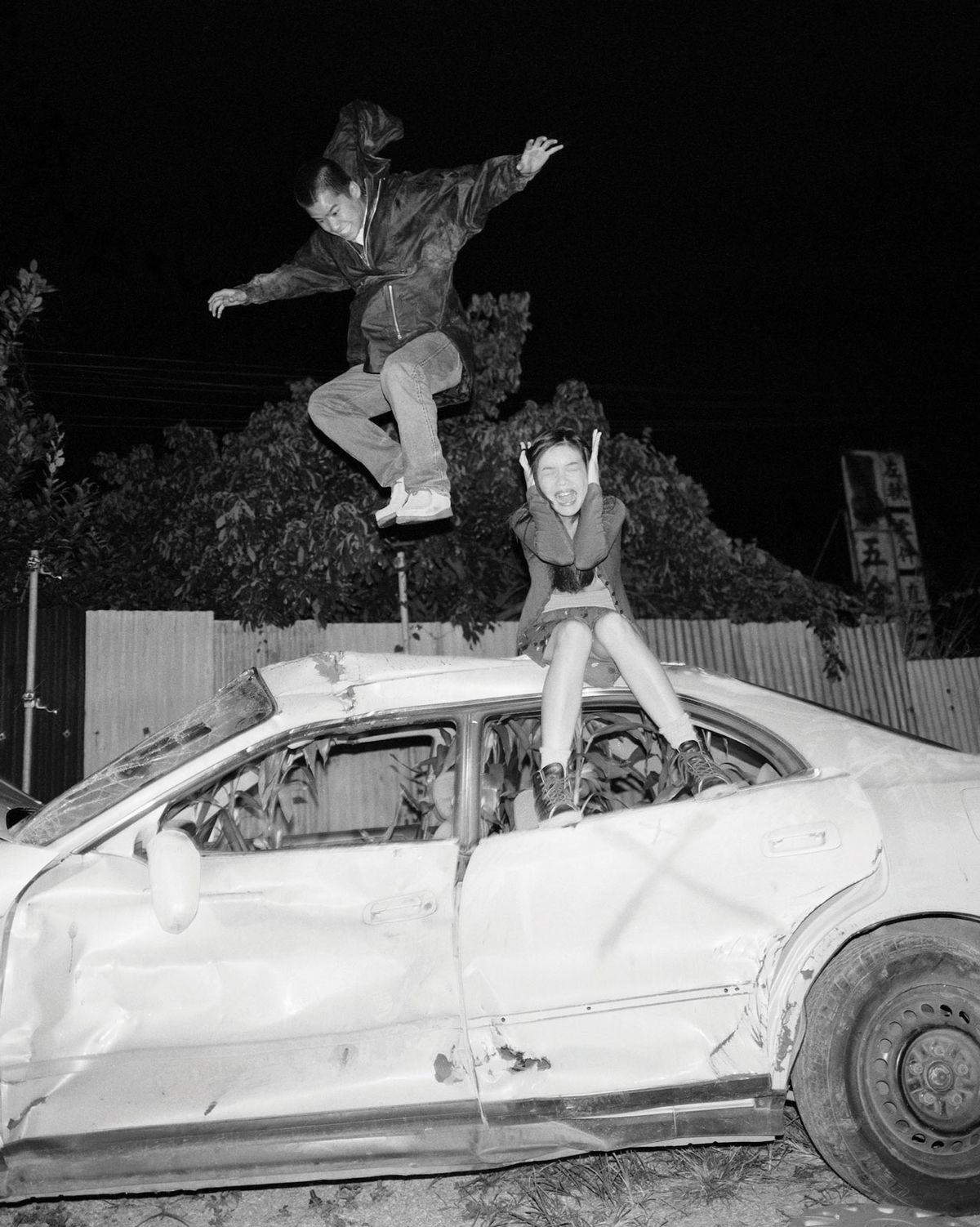

Kai Fusayoshi’s Spring’s Come and the Riverside Napping Population Grows (1996) © Kai Fusayoshi

At Kyoto’s train station, a glance at the underside of the aerial pathways that run like arteries through the station’s cavernous glass archways will reveal more than 100 large-scale portraits of Kyoto’s past youth. This will be the work of Kai Fusayoshi, well-known in Kyoto as the long-time and gregarious owner of Hachimonjiya, a battered, late-night dive bar on the banks of the Kamogawa River. In between serving sake, Fusayoshi has photographed the loners and lovers who congregate by the banks of the river. Gathered together, his images will animate one of Japan’s busiest thoroughfares.

Kyotographie’s founders, the 47-year-old French photographer Lucille Reyboz and her Japanese partner, the 52-year-old lighting director Yusuke Nakanishi, had no previous curating experience before establishing the festival. Both had visited the Les Rencontres d’Arles festival in the south of France and aspired “to create a stage in Japan”.

“Japan is rich in talented photographers, and it seemed unfortunate there were not many opportunities to value them in the country,” Reyboz says. Recreating Arles in Kyoto—and getting the local populace onside—has taken time. “The people in Kyoto don’t express themselves directly,” Reyboz says. “There are numerous rites of passage one must overcome to achieve a sense of trust and confidence.”

Wing Shya's In the mood for love (2000) Courtesy of Wing Shya

The festival is reliant on private philanthropy, as well as fairly visible sponsorship from brands such as Chanel and Ruinart champagne. While coming with its own pressures, this frees the festival from dealing with the restrictive officialdom of Kyoto’s local government, allowing Reyboz and Nakanishi to explore issues often not properly acknowledged by Japan’s government, or polite society at large. The festival, then, sees discursive curation as a founding principle.

“When the Great East Japan Earthquake and the [Fukushima] accident occurred in 2011, I thought that it was important to be aware of what is going on in this country, and be decisively self-conscious of how information is manipulated or hidden from us,” Nakanishi says.

The festival was created soon after the 2011 meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear plant. Reyboz and Nakanishi plan to dedicate its ninth edition, slated for April 2021, to the multivalent, insidious impact the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster had on Japanese society. The strand is being organised by photojournalist Kazuma Obara, the first image-maker to gain access to the plant after the disaster. The outcome is sure to be fascinating, and a true testament to photography’s ongoing power to see and show the truth.

• Kyotographie, various venues, Kyoto, 19 September-18 October